Three gifts for a Zen ChristmasIn the traditional Nativity story that I grew up with, three travellers come all the way to Bethlehem to present the baby Jesus with three gifts. Buddhism also has three 'treasures', and so this week we're going to take a look at what they are.

(Yeah, I know it's a stretch. I foolishly promised my Wednesday night class that I'd try to think of a festive-themed class for the end of the year, and this is the best I could do. Please just pretend it's a stroke of genius, and read on anyway!) What are the Three Treasures? Also known as the Triple Gem, Three Jewels or Three Refuges, the Three Treasures are three key aspects of Buddhist practice: Buddha, Dharma and Sangha. Between them, they offer a framework of support for anyone wishing to travel the Buddhist path. But why do we need support in the first place? Because the path is hard! Meditation can be difficult, frustrating or boring at times; our practice can go through periods where it doesn't really seem like it's helping any more, like we've forgotten what we're doing or (worse) that it was never actually working in the first place. Many of the classic texts (and probably a fair few of my articles) make it sound like the moment you hit a meditation cushion your experiential reality will be transformed into sacred wonder and you'll never have another bad day ever again, but the reality is not always so appealing. Of course, in the long run practice really does enrich our lives in profound ways (I wouldn't devote so much time and effort to teaching if it didn't!), but at times it can be hard to remember that. And so we have these three treasures, or three refuges - three factors that we can turn to for support when we need it most. So let's take a look at them! Buddha At the simplest level, 'Buddha' refers to the historical figure of Siddhartha Gautama, also known as Shakyamuni ('sage of the Shakya clan'). Siddhartha is the O.G. Buddha, founder of the whole tradition - according to the stories, the son of a king who abandoned his inheritance to become a homeless wanderer, searching for a solution to the problem of suffering. After many trials and tribulations he eventually found what he was looking for, and spent the last 45 years of his life teaching it to anyone who would listen. The legacy of his remarkable life is both one of the world's great religions, and a remarkably practical approach to examining one's experience and coming to understand how we can suffer less and be kinder, more compassionate people. Siddhartha wasn't the only buddha, however. In some of the early discourses he talks about himself as the seventh in a line of historical buddhas. Later on, many more buddhas and bodhisattvas were added to the collection. Over time, Buddhism developed a pantheon of figures associated with different qualities - for example, Amitabha Buddha presides over the Pure Land, located west of Mount Sumeru in Buddhist cosmology, and the Pure Land sect of Buddhism is essentially devoted to the worship of Amitabha. There are many other inspiring figures among the buddhas and bodhisattvas, notably including the bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara/Kuan Yin/Kannon, considered to be the embodiment of compassion, and Manjushri, the embodiment of wisdom. Many stories are told about these figures in the classic texts, and they can be brought to mind as a source of inspiration if you're that way inclined. On the other hand, if this is all sounding a bit mythological and abstract, we can also look at the term 'Buddha' as referring simply to the great teachers of the tradition, including those in our lineage, and perhaps even those alive today. After all, we have to learn this stuff somehow, and the reason that so many wonderful, powerful spiritual teachings are available to us today is because of the patient efforts of many generations of men and women who have investigated, understood and subsequently embodied them in order to pass them on to the next generation in turn. We live now in a remarkable era in which Zen masters and senior teachers from other traditions offer their guidance freely over the Internet, which is pretty amazing when you really stop to think about it. Finally, one more (comparatively esoteric) meaning of 'Buddha' is our own awakened nature. Whether we have immediate access to a human teacher or not, our own Buddha Nature is always with us - it's only difficult to see because it's so close. And as our practice goes deeper and we see more of who we really are, we can learn to trust our inherently awakened nature, and come to rely on it to get us through even the toughest times. Dharma The second of the Three Treasures is the Dharma, which in this context typically means 'the teachings of the Buddha'. Of course, as we've explored recently, different iterations of Buddhism have taken different approaches to the problem of suffering; depending on how you look at it, you might see that as multiple paths within one Dharma, or multiple Dharmas serving slightly different needs within different contexts. Either way, though, we do have this body of teachings to inspire, instruct and guide us in our explorations of ourselves and our world. And while in the previous section I highlighted the role of teachers throughout the ages in passing the Dharma down to each new generation, we can also look at the teachings as they stand apart from the imperfect human individuals involved in the chain of transmission. Sadly, it isn't hard to find examples of senior teachers who have betrayed the trust that their students placed in them in all kinds of terrible ways. But to focus too much on high-profile cases of wrong-doing at the expense of the tremendous benefit that the teachings bring to millions of people worldwide is to throw the baby out with the bathwater. Furthermore, the Dharma provides us with a tremendous resource of time-tested practices. It can be tempting to go one's own way with meditation practice and ignore all the tedious bits in an established tradition, or to follow a charismatic guru who claims to have awakened spontaneously with no formal instruction, but in turning away from the established traditions we miss out on the opportunity to benefit from thousands of years of research and development, thousands of years of testing and refining the practices that have proven time and again to work well. The more I study Zen, the more I discover the purpose of even those aspects of the path that I initially dismissed as 'just tradition' or 'just a cultural thing', and over time I've (hopefully!) become a little more humble and a little less likely to assume that I can immediately tell what's useful and what isn't. Finally, just as Buddha can be interpreted esoterically as a reference to our own awakened nature, Dharma can be interpreted as a reference to reality itself. The Tang dynasty Zen master Nanyang Huizhong said that the Buddha mind is 'fences, tiles, walls and pebbles' - in other words, the everyday things of the world. Sometimes it can seem like Zen teachings point to something very remote and special, but time and again Zen stories point us back to the world that's right in front of us. There's no need to go somewhere special to find it - it's already here. Sangha The final 'jewel' is the sangha - the community of practitioners. Traditionally, the term was used in a few different ways. At times, it referred specifically to the monastic community, while at other times it indicated those practitioners (lay or monastic) who had attained at least the first stage of awakening, stream entry, and could thus speak from a place of genuine personal insight rather than simply repeating the words of others. Perhaps the most inclusive traditional use of the term is the 'fourfold sangha' - the collection of monks, nuns, male householders and female householders. I tend to regard 'sangha' as simply 'people who practise', with no need for further subdivision - all are welcome. We are tribal creatures, and it can be immensely supportive to be in a group with people who share our interest in meditation. I read a study recently which suggested that perhaps the majority of the benefit of eight-week mindfulness courses actually came from the community aspect of the course rather than the practices themselves! Sitting with other people on a regular basis can also help us to keep the practice going when times are tough - the first time I attempted a solo retreat (during last year's lockdown) I realised how much I rely on my fellow practitioners in the meditation hall to carry me through the sitting periods at times. Of course, it isn't all roses. From time to time, those people will almost certainly get on our nerves and challenge us in ways that we'd prefer not to be challenged. But in some ways, even this is a benefit in disguise. A senior teacher once quipped that 'some people are arahants (fully enlightened) only on retreat'. It's easy to be enlightened in a cave where there's nobody to bother you! Jack Kornfield's excellent book 'After the Ecstasy, the Laundry' has a great story about an order of nuns who maintained a vow of silence for many years, then one day decided to reintroduce speech - and were horrified to discover how challenging it was to maintain the boundless love they had experienced for each other in silence. One more point about sangha is that it provides us an opportunity for ritual. It's easy to be a little suspicious of ritual, which can come across as quaint, archaic, or perhaps even as a kind of cultural appropriation. But ritual can also be seen as serving a kind of social function. When we get together in a certain context, we agree to behave in certain ways and follow certain rules - for example, during the group meditation we all sit in silence (more or less!) until the bell rings, rather than getting up and walking around or texting our friends. There's nobody to enforce those rules, but generally speaking we're happy to follow them, because they support our collective practice. In this sense, ritual can be seen as a physical enactment of our values - we gather together and agree to behave in a certain arbitrary way together, because that ritual represents our collective aspiration to be the type of people who meditate. Setting an intention goes a long way in this business, and having other people to remind us of that intention and help us to uphold it can be tremendously supportive. A final note for 2021 This is my last article for the year - I'll be back teaching from January 5th, so the first article of 2022 will appear on January 6th, all being well. I'd like to thank everyone who reads these articles, and wish you well for the festive period. I hope you have the opportunity to spend some quality time with your loved ones. See you all in the New Year!

0 Comments

Three simple steps to energy cultivation in ZenThe energetic side of Zen practice is something I probably don't emphasise enough, so this week we're going to take a look at it in some detail.

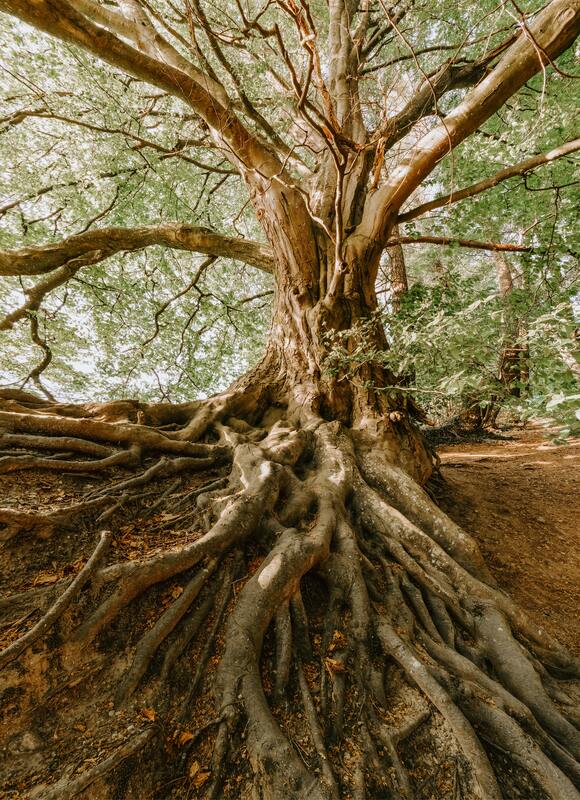

It's easy to assume that Zen is primarily or exclusively a mental activity - when we think of Zen, we think of meditation, long periods spent sitting with closed eyes doing something-or-other with the mind. But meditation, or zazen, is really just one part of Zen practice. Zen is ultimately a way of life, and has practices for every aspect of our lives. In particular, and following on from the discussion of the importance of view a couple of weeks ago, the aim of Zen practice is explicitly not to transcend our problematic meat-based existence and float off on a cloud of samadhi. As we see from the famous Zen Ox-Herding Pictures, although we may deliberately remove ourselves from the world at times in order to deepen our practice, ultimately we aim to return to the world to be of service to those around us. And in order to live in the world, we need good health and plenty of energy to deal with whatever our lives will throw at us! Consequently, in Rinzai Zen we have a set of energy practices which cultivate a kind of grounded power which will sustain us even when life places great demands on us. So let's take a look at them! What do you mean by 'energy' anyway? As living creatures, we experience the natural ebbs and flows of our vitality from day to day. Some days we wake up raring to go, while other days it's a struggle to get going until we've had our third coffee of the morning. After a prolonged period of exertion, we start to feel burnt out - our vitality depleted in a more serious way, that will take more than a good night's sleep to recharge. Traditional Chinese medicine has taken this simple, intuitive experience of vitality and developed an elaborate model of the body around it - a model which forms the basis for acupuncture and qigong, amongst other things. The extent to which this model is accepted varies quite widely in the West - some people fully embrace it, some are much more sceptical. Personally, I was willing to give it a go but by no means convinced by the traditional explanations, and I think that may be a good way to approach these practices. In my own experience, they do work - and they seem to work regardless of how sceptical or credulous I'm feeling about them on any given day. I've gone through periods where I've been totally convinced by the traditional explanations, and periods where I've been equally convinced that we need to know what's 'really' going on in Western scientific language, but the practices have continued to do what they do regardless. The importance of 'hara' In Japan (where my Zen lineage comes from), great emphasis is placed on the cultivation of 'hara'. Anatomically, this refers to the abdomen; colloquially, it can be used to mean something very close to 'guts', both in the biological sense and in the sense of having the courage and fortitude to persist even in difficult circumstances. Energetically, the hara is also the home of the tanden (Chinese: dan tien), which is considered the central nexus of the body's energy network. The tanden, and by extension the hara, can be viewed as a kind of 'battery pack' - if our hara is well-supplied with energy, we are likely to be strong and vital, whereas if our hara is depleted, we're likely to be tired and weak. Indeed, there's a sense that we can 'carry' our energy in various places in the body - in particular, the head, the heart, and the hara. The Zen view of the ideal person is triangle-shaped - a little in the head, a bit more in the heart, with the majority in the hara. Excessive 'headiness' is associated with people who are overly intellectual, fussy or pedantic (like me!), while excessive 'heartiness' is associated with people who are overly emotional, flighty and prone to drama. Excessive 'hara-ness' might show up as stubbornness, and it does need to be balanced with some cultivation of both heart and head, but generally speaking most of us in the West need to focus first and foremost on hara cultivation - we have more than enough in our heads and hearts already, and building up a solid hara provides much-needed stability and balance. So how do we go about tuning up our energy system? Stage 1: Connecting with the hara Before we start working deliberately with energy, it can be hugely helpful to get in touch with our hara. As I mentioned, for many of us in the West, it's a new concept. The good news is that it isn't just a theoretical, esoteric idea - it's something that can be experienced very clearly on a physical level. The quickest way to get a tangible sense of the hara is to use 'Ah-Un breathing'. This short, simple practice uses a couple of special breaths, making an 'ah' sound on the inhale and an 'unnnn' sound on the exhale, to energise the front, sides and back of the hara. There's a full guided practice on my Audio page - check out the 'explanation of breaths' audio first to make sure you know how you're supposed to be breathing, and then use the 'guided practice' audio to do the practice itself. Even one time through the Ah-Un breathing can be enough to give you a clear sense of the hara, but I recommend doing it every day for a month or so to really ingrain the feeling into your body. The clearer it is, the easier the subsequent practices will be. Stage 2: Grounding practices to bring energy down from the head and heart Once you've got a clear sense of the hara, you're ready to start working with energy directly. A good place to begin is with some grounding practices, particularly if you have a strong meditation practice, and even more particularly if your meditation practice involves focusing on the breath at the nostrils. There's an oft-repeated saying that 'energy flows where attention goes', and samadhi practices in particular are good for generating and focusing energy. (Readers familiar with jhana practice will recognise that focusing the mind steadily enough produces the very strong energetic experience that is the first jhana.) But even if you aren't into hardcore samadhi stuff, meditation practices which involve focusing your attention on your head will tend to bring energy up. (And, of course, that goes double if you do practices like kundalini yoga which are all about bringing your energy up the spine to the head.) While some teachers will tell you that bringing energy to the head may trigger spiritual experiences, it's more often the case that it simply causes headaches (which can get seriously bad, especially if combined with wider life stress). According to my teacher, the problems are usually caused by people trying to climb too high too soon, like a tree without adequate roots. So in the Zen approach we start by grounding. Two nice grounding practices are the 'soft ointment' meditation and the 'naikan' practice, both of which are available in guided form on my Audio page. Soft ointment is a kind of body scan in which you imagine a small ball of soothing, cleansing, healing ointment placed on top of your head, then feeling it melting slowly down through the body, washing away any energetic blockages as it goes. When the whole body has been washed clean, the lower part of the body (up to the level of the navel) then fills up, leaving you with a sense of grounded stability in the lower half of the body and relaxed openness in the upper half. Naikan is a practice which can be done standing, sitting, lying down or all three, and which uses a combination of arm movements and focused attention to open the body up to receive fresh energy from our surroundings and draw it down into the hara and the legs. As with soft ointment, the practice leaves us feeling grounded and energised in the lower body, relaxed and open in the upper half. Stage 3: Generating and circulating energy So now that the foundation has been laid and the engine has been tuned (if you'll excuse the mixed metaphor), it's time to get serious about energy. (And if you're the kind of person who sees a statement like that and immediately wants to skip the first two stages and jump right in here, please don't! I did that too, and got nowhere with these practices for ages, then ramped up the practice in the hopes that something would happen and gave myself a really sore head and not much else. Please take the time to build the foundation - you'll thank me later.) The key practice here is known by various names within Zen, including 'naitan' (which means something like 'inner transformation') and 'tenborin' (which means 'turning the wheel of Dharma'). It's also known in qigong circles as the 'microcosmic orbit'. We start by focusing the attention on the tanden. Where attention goes, energy flows. This first part of the practice is about charging up our battery pack - powering our energetic core until our vitality is so abundant that it overflows, like a cauldron filled to brimming and beyond. Then we begin to move our attention gently and deliberately up the back of the body on an inhale and down the front of the body on an exhale, This encourages the energy to circulate throughout the body, thus distributing the vitality we've generated to wherever it's needed. When we're ready to close the practice, it's helpful to return to the tanden for a few breaths, to seal the energy back in. As with the other practices above, you can find a guided audio for naitan on my Audio page. I'm trying it but nothing is happening! A common experience for first-timers is to try these practices but feel nothing. Where's this mysterious 'energy' that he keeps talking about? Is it actually a load of woo-woo nonsense? All I can say is - be patient. It takes a while to connect with the sensations in these practices, but most people find that it comes into focus sooner or later. Remember, energy flows where attention goes, so even if you don't actually feel it yet, simply doing the practices and focusing your attention in the correct manner is likely to be having an effect - you just aren't quite tuned into the right wavelength to feel what's going on yet. (And yes, I realise that this explanation probably won't convince you if you can't feel anything yet!) Happy cultivating - may you be grounded, powerful and vital in every aspect of your life. |

SEARCHAuthorMatt teaches early Buddhist and Zen meditation practices for the benefit of all. May you be happy! Archives

June 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed