Unusually clear advice from Zen master DogenThis week we're going to take a look at some guidelines for Zen practice written by the great Soto Zen master Eihei Dogen in the 13th century. If your heart sinks at the mention of Dogen's name, fear not - unusually for Dogen, they're comparatively straightforward and accessible!

Eihei Dogen, 1200-1253 Dogen is one of the greatest Zen masters who ever lived, and is the founder of the Japanese Soto Zen lineage. Dogen started out in the Tendai school of Buddhism, who promoted the idea of 'intrinsic awakening' found in (for example) the Lotus Sutra; like many who encounter that approach, Dogen wanted to know 'If I'm enlightened already, why do I need to do all this practice?' Dogen wasn't satisfied with the answers he was given, which largely boiled down to 'Because we say so', and so ultimately he went to China in the hope of finding a more satisfying answer. Evidently he did, because he came back to Japan a changed man, founded a succession of Zen monasteries and taught in the Soto style for the rest of his (sadly short) life. Soto Zen stresses the primacy of shikantaza ('just sitting') as the main (and often only) practice. (I'm going to pick out the key points, but if you want to read the whole text, you can find some translations here - scroll down for the text. I'll use the Brown/Tanahashi translation for the headlines, and offer the Nishijima translation for the alternative readings.) 1. You should arouse the thought of enlightenment. (Alternatively: Establish the will to the truth.) My teacher's teacher, Shinzan Roshi, likes to say 'First priority is kensho [awakening]; second priority is kensho; third priority is kensho.' It's pretty common today to find meditation teachers presenting it as a kind of psychologised self-therapy, as a performance enhancer, as a tool for relaxation and stress relief, and so on. And that's fine - it can be used for all those things, quite effectively. But the purpose of Zen practice goes beyond those applications, to something much more fundamental - to awaken us to who we really are, much deeper than the level of our thoughts or personality. Zen awakening is about discovering for ourselves the true nature of who we are and what our subjective experience actually is, and radically changing our relationship to everything that we encounter. So Dogen wants to stress that we should hold this 'thought of enlightenment' - the intention to look deeply into our experience, not settling for less than full awakening. He says: 'If in the past or present, you hear about students of small learning or meet people with limited views, often they have fallen into the pit of fame and profit and have forever missed the buddha way in their life. What a pity! How regrettable! You should not ignore this.' He also gives us a practice instruction: 'Just forget yourself for now and practice inwardly—this is one with the thought of enlightenment. We see that the sixty-two views are based on self. So when a notion of self arises, sit quietly and contemplate it. Is there a real basis inside or outside your body now? Your body with hair and skin is just inherited from your father and mother. From beginning to end a drop of blood or lymph is empty. So none of these are the self. What about mind, thought, awareness, and knowledge? Or the breath going in and out, which ties a lifetime together: what is it after all? None of these are the self either. How could you be attached to any of them? Deluded people are attached to them. Enlightened people are free of them.' 2. Once you see or hear the true teaching, you should practise it without fail. (Alternatively: When you meet and listen to the authentic teachings of Gautama Buddha, be sure to learn them through practice.) Dogen's instructions here are brief and to the point. In the same way that a king should take heed of the advice of his wise ministers and follow through on that advice, those who hear the teachings of Zen shouldn't stop there, but must actually practice it for themselves in order to realise the truth. Hearing the teachings is only the first step, and is frankly pretty worthless unless backed up by your own direct experience. 3. In the buddha way, you should always enter enlightenment through practice. (Alternatively: To enter into and experience Buddhism, always rely upon practice.) Dogen now elaborates on the nature of practice. He points out that different people will practise in different ways - each person has affinities for certain practices and difficulties with others - but in all cases practice is required. He also offers some encouragement. 'You should know that arousing practice in the midst of delusion, you attain realization before you recognize it. At this time you first know that the raft of discourse is like yesterday's dream, and you finally cut off your old understanding bound up in the vines and serpents of words. This is not made to happen by Buddha, but is accomplished by your all-encompassing effort.' And this is very true - while we occasionally have moments of breakthrough in practice, often it's a long, slow process in which nothing much seems to be happening for long stretches of time. But if we keep going, sooner or later we'll get where we're going - not because the teacher decides to 'bless' us with enlightenment as a reward for our practice, but because we've done the work ourselves. 4. You should not practise Buddha's teaching with the idea of gain. (Alternatively: Do not practise Gautama Buddha's teachings with the intention of getting something.) Dogen counterbalances the emphasis of the previous point, so that we don't fall into the trap of self-centredness. Yes, we must do the practice ourselves; yes, enlightenment comes as the fruit of our own efforts rather than as a gift from the teacher; and yes, enlightenment brings tremendous benefits. However, in order to see who we really are, we have to let go of who we think we are right now. If we pursue Zen practice as a way of getting something good for ourselves that other people don't have, as a way of earning a trophy to put in our spiritual display cabinet, we're not only missing the point but actually reinforcing precisely the self-centred way of relating to the world that we need to move beyond in order to wake up. Dogen emphasises this point: 'Clearly, buddha-dharma is not practiced for one's own sake, and even less for the sake of fame and profit. Just for the sake of buddha-dharma you should practice it. All buddhas' compassion and sympathy for sentient beings are neither for their own sake nor for others. It is just the nature of buddha-dharma.' 5. You should seek a true teacher to practise Zen and study the way. (Alternatively: To practise Zazen and study the truth, look for a true master.) Having access to a teacher is a powerful support for any contemplative or spiritual practice. Books and YouTube videos (and blogs like this!) are all well and good, but they can only ever present very generalised instructions. A good teacher can work with you as an individual to understand your particular circumstances and give you tailored advice to help you move forward. These days, access to teachers is easier than at any previous point in history. You don't need to travel hundreds of miles on foot through the mountains of China to reach a monastery - you can attend teachings, sit in meditation and have Skype interviews with Zen masters online (see the Zenways website for more details on how to connect with my teacher Daizan). And, of course, I also run an online class on Wednesdays, although I'm not a Zen master, so take whatever I say for what it's worth! Actually, Dogen also has some advice on how to recognise a true teacher: 'Regardless of one's age or experience, a true teacher is simply one who has apprehended the true teaching and attained the authentic teacher's seal of realization. One does not put texts first or understanding first, but one's capacity is outside any framework and one's spirit freely penetrates the nodes in bamboo. One is not concerned with self-views and does not stagnate in emotional feelings. Thus, practice and understanding are in mutual accord. This is a true master.' So there you go - five points to consider in your practice. Come back next week for the second half of this text, and five more pearls of Dogen-shaped wisdom!

0 Comments

More practice advice from Zen master DogenThis week we're looking at the second half of Gakudo-Yojinshu, 'Advice on studying the way', written by the great Soto Zen master Eihei Dogen in the 13th century. (You can find the first half of the text, and a bit of background about Dogen, in last week's article.)

(As with last week, I'm going to pick out the key points, but if you want to read the whole text, you can find some translations here - scroll down for the text. I'll use the Brown/Tanahashi translation for the headlines, and offer the Nishijima translation for the alternative readings.) 6. What you should know for practising Zen. (Alternatively: What we should know in practising Zazen.) Dogen starts this lengthy section by emphasising that Zen practice is not quick or easy, and you shouldn't expect it to be that way. The ancestors of the past made tremendous sacrifices to practise as diligently as they could for our benefit, and we should expect our own practice to be similar. If you've been following this blog for a while, you'll have seen me say the exact opposite - that beginners should find something they find relatively easy as a way in - perhaps an approach which is enjoyable, interesting, or seems to come naturally. So am I saying Dogen is wrong? Heck no - in a Dharma battle between the greatest Soto Zen master in history and me, I know who's going to win. But I still stand by what I wrote. Dogen was writing for monastic practitioners, encouraging them to work hard and use their time well. The students I tend to encounter already have full lives, jobs, families, complex domestic situations and all the rest of it, and so it's a big deal even to come to a single class and think about trying out meditation, let alone find twenty minutes a day for an on-going practice. The key thing in the early stages is to build the habit of practice until it becomes clear that this is something that's going to be useful in our lives, after which the motivation to continue develops more naturally and we can start to look at cranking things up a bit. After delivering his opening salvo, Dogen then changes tack to something much more encouraging. He notes that success in Zen practice is not a matter of bone-crushing austerities, not a matter of being highly intelligent or well-read, not a matter of being philosophically inclined, not a matter of being young or old, not dependent on good health, and not limited only to men (he specifically cites the example of an excellent 13-year-old female practitioner). Rather, the practice is available to anyone willing to dedicate themselves to it and put in the practice hours on the cushion. Finally, he offers a typically Zen warning against relying too much on the thinking mind: 'Students should know that the buddha way lies outside thinking, analysis, prophecy, introspection, knowledge, and wise explanation. If the buddha way were in these activities, why would you not have realized the buddha way by now, since from birth you have perpetually been in the midst of these activities? Students of the way should not employ thinking, analysis, or any such thing. Though thinking and other activities perpetually beset you, if you examine them as you go your clarity will be like a mirror. The way to enter the gate is mastered only by a teacher who has attained dharma; it cannot be reached by priests who have studied letters.' 7. Those who long to leave the world and practise buddha-dharma should study Zen. (Alternatively: Any person who hungers to practise Buddhism and to transcend secular society should, without fail, practice Zazen.) This section is largely a polemic about how great Zen Buddhism is and how sad it is that there are dark corners of the world where people still follow other teachings and traditions. These things crop up throughout Buddhist history, but I've never found them particularly interesting - clearly I'm a big fan of Zen myself, but I also have a lot of respect for the world's many other great contemplative traditions, and wouldn't want to throw them out just because they aren't 'Zen' enough for me. 8. The conduct of Zen monks. (Alternatively: About the conduct of Buddhist priests and nuns who practise Zazen.) From the title of this section, you might think it would have something to do with the monastic precepts, or one of Dogen's famous lists of incredibly detailed, precise instructions governing every activity taken throughout the day in his monastery. Actually, though, most of this section is a compilation of Zen stories, in highly condensed form, pointing to the many occasions in the Zen records of great masters waking up. He then concludes with another practice instruction. As an aside, Dogen, and the Soto lineage in general, is overwhelmingly associated with shikantaza, a just sitting practice, and it's sometimes thought that meditative inquiry and investigation has no place in Soto Zen. From the following passage, I think it's clear that that's not the case at all: 'Please try releasing your hold [on conceptuality], and releasing your hold, observe: What is body-and-mind? What is conduct? What is birth-and-death? What is buddha-dharma? What are the laws of the world? What, in the end, are mountains, rivers, earth, human beings, animals, and houses? When you observe thoroughly, it follows that the two aspects of motion and stillness do not arise at all. Though motion and stillness do not arise, things are not fixed. People do not realize this; those who lose track of it are many. You who study the way will come to awakening in the course of study. Even when you complete the way, you should not stop. This is my prayer indeed.' 9. You should practise throughout the way. (Alternatively: Direct yourself at the truth and practise it.) In this section, Dogen sketches an outline of how the path unfolds. He suggests that beginners should sit and 'sever the root of thinking' (in other words, connect with direct experience rather than thinking about your experience) - he goes as far as to say that 'If once, in sitting, you sever the root of thinking, in eight or nine cases out of ten you will immediately attain understanding of the way.' Once you've developed the knack of sitting without being constantly bound up in intellectual activity, then continue to sit that way, 'let[ting] body and mind drop away and let[ting] go of delusion and enlightenment'. The more you do this, the more you become immersed in the way, and 'for those who are immersed in the way, all traces of enlightenment perish'. In Zen practice, kensho is just the beginning of awakening. It's necessary to continue to practise, deepening your insight into who you really are and integrating it fully into your life. This process of sudden awakening followed by gradual cultivation is described in several of the classic Zen maps, such as the Ox-herding Pictures and Tozan's Five Ranks. In all cases, the final goal is not some kind of transcendent condition where you float several feet above the ground shooting rainbows in all directions, but actually that you become completely and utterly ordinary, but at the same time completely and utterly in accordance with the way. Hence 'all traces of enlightenment perish' - while we're still attached to the sense of ourselves as 'an awakened person (look at me!)', there's still much further to go. So we don't stop after kensho - as Daizan likes to say, we don't just get out the deckchairs and wait to die. We keep going, working in the world for the benefit of those around us, letting go of every last trace of our enlightenment. 10. Immediately hitting the mark. (Alternatively: Taking a direct hit here and now.) For this final section, I'm just going to let Dogen speak for himself. 'There are two ways to penetrate body and mind: studying with a master to hear the teaching, and devotedly sitting zazen. Listening to the teaching opens up your conscious mind, while sitting zazen is concerned with practice-enlightenment. Therefore, if you neglect either of these when entering the buddha way, you cannot hit the mark. 'Everyone has a body-and-mind. In activity and appearance its function is either leading or following, courageous or cowardly. To realize buddha immediately with this body-and-mind is to hit the mark. Without changing your usual body-and-mind, just to follow buddha's realization is called "immediate," is called "hitting the mark." 'To follow buddha completely means you do not have your old views. To hit the mark completely means you have no new nest in which to settle.' So there you have it. You've heard the teaching - now go and sit zazen, and hit the mark right now! How to work with 'non-literal' practice instructionsI received a question recently about an instruction I'd given in that evening's koan practice - to 'put the question into your belly'. (I'd actually just finished a Korean Zen retreat with Martine Batchelor, who gave that same instruction, so it was fresh in my mind when we looked at the question 'What do I know for certain?' in last week's class.)

The questioner expressed a sentiment that I've shared many times in my own practice: how is one supposed to work with seemingly non-literal instructions? How can one, for example, 'breathe into the feet', when the lungs are in the chest? How is one supposed to 'be like a mountain' if we aren't rocky and over a thousand feet tall? And how is one supposed to 'put a question into one's belly'? Surely thoughts live in the head - we can't move our brains! Different ways of using language Over the last two and a half thousand years of contemplative practice, different cultures and different traditions have found wildly different ways to describe the territory we explore in meditation. The earlier tradition of Indian Buddhism - as represented in the Pali canon, for example, but especially in the commentarial tradition that came from it, including the Abhidhamma and texts like the Visuddhimagga - tends to be logical, descriptive, list-based, at pains to be precise and technical. On the other hand, the later tradition, particularly as exemplified by Chinese Buddhism, is frequently poetic, flowery, full of paradox and imagery. Indian Buddhism might say something like 'In this practice, pay attention to the arising and ceasing of mental factors; here is a complete list of the 52 mental factors which can arise and cease.' Nice and neat, if perhaps a little pedantic at times. On the other hand, Chinese Buddhism features koans such as 'A monk asked Joshu, "What is the meaning of Bodhidharma's coming to China?" Joshu said, "The oak tree in the garden."' Riiiight. Since my own background is in both early Buddhism and Zen, I've seen the benefits of both approaches, and also have some sense of where I've personally found each approach a little frustrating at different times. I've seen people fall in love with the clarity and precision of early Buddhism after spending many frustrating years banging their head against Zen practice; I've also seen people literally 'wake up' and come more fully alive when exposed to a tradition like Zen which incorporate art, metaphor, imagery and poetry after years of clinging to a narrow interpretation of a limited set of instructions. I've also found that, as a teacher, one of the greatest challenges is to find a way of expressing the Dharma which connects with each listener, with their unique background, conditioning and preferences. What works for one person might not land so well with another, and it's often hard to tell when everyone is sitting quietly, sometimes even with their eyes closed. As a result, I tend to use a range of different approaches. (If you've been reading these articles for a while, you've probably noticed this already!) Even when teaching the same practice I'll sometimes word the instructions differently, in case a different phrasing makes it 'click' for someone when it had previously left them cold. Another benefit of this approach - at least as I see it - is that we can start to build up a kind of 'translation guide' for crossing the boundaries of different traditions, teachers and ways of expressing the core ideas of contemplative practice. If we can learn to recognise the same ideas expressed in different ways, a much greater body of spiritual and contemplative literature becomes accessible to us, and we can gain greater confidence that what we're doing is part of a vast human tradition of awakening which is available to everyone, not some narrowly defined 'secret truth' which is available only to the initiated in one specific sect. Non-literal practice instructions When it comes to non-literal practice instructions ('breathe into your heels', 'sit like a mountain'), these can serve several purposes, depending on who's listening to them. Poetic language may strike a chord with someone who finds technical language too dry; and poetic language is also a subtle reminder that no instruction, no matter how precise, is ever it - the best we can ever do is point to it. The shifts and insights of Zen are not purely conceptual and cannot be expressed purely in conceptual terms, and whenever you find yourself caught in a theoretical, intellectual debate which is not grounded in practical experience, it can be helpful to remind yourself of this. (One interpretation of the famous koan about Nansen's cat is that Nansen is showing how too much intellectual engagement 'kills' the Dharma.) However, we can also find ways through practice of relating to statements which initially seemed to be only poetic. For example, the great Soto Zen master Dogen talks about how 'grasses and trees, fences and walls demonstrate the Dharma for the sake of living beings'. On one level, this can be taken as a poetic metaphor that 'the truth is all around you', close at hand rather than far away on some mountaintop. You can also see it as a coded description of the fabricated nature of experience - pointing out that it isn't just 'my thoughts' or even 'my sense of self' which are mind-originated, but also everything that we typically perceive as 'outside us'. Actually, though, even with something that looks at first glance like metaphor or poetry, we can find a concrete, practical way to work with it - to turn it into a specific practice instruction. Let's say we're doing koan practice, working with the question 'What is this?' (The word 'this' in the question is usually taken to mean something like 'this present moment experience', so the koan is a way of exploring our immediate subjective experience, right here and now, as opposed to speculating intellectually about metaphysics or whatnot.) Normally, the practice loop goes like this:

But instead, if we understand (and ideally have some direct experience of) the view of emptiness/the mind-originated nature of things, we can remind ourselves just before we begin the practice that everything we ever experience (including grass and trees, fences and walls) has the same ultimate nature, and so it's just as valid to ask 'What is this?' of a tree as it is of a body sensation, an abstract idea about what 'this present experience' actually is, or anything else. So then the practice loop becomes:

(For the avoidance of doubt, the idea of step 4 is not that we start trying to understand what a tree is made of, how big its root system is or where it gets its nourishment, etc. - the point is the instantaneous recognition that 'the-appearance-which-we-label-tree' is just as much an expression of mind-nature as anything else, and so there are no 'right' or 'wrong' referents for 'this' in the question.) Notice that the loop is a little tighter, the return to the practice a little more efficient, and also it helps to dissolve the apparent duality between 'asking the question correctly' and 'being distracted by something irrelevant' - instead, we can integrate the question into every experience. This not only helps the on-cushion practice but also helps us to bring the sense of questioning associated with the koan into our everyday activities, which makes the inquiry vastly more powerful - the more we can hold the question in mind, even in the background, the deeper the investigation will go. In the long run we want our awakening to touch every aspect of our lives, not just the time we spend sitting quietly on a cushion. So how do I put a question into my belly? Now, specifically in relation to the weird business about putting the question into the belly, again we can look at this on several levels. For some people, particularly the more intuitive types, this may be all the permission you need to throw off the shackles of intellectual thinking right away, perhaps bringing to mind the association of 'gut feeling' with intuitive wisdom and so forth. But we can also work with this instruction on a more technical level - actually, in a few different ways. The simplest way to 'put the question in the belly' is to combine asking the question (50% of your attention is on 'What is this?') with paying attention to the physical sensations in your lower abdomen (50% of your attention is on the space of the tanden, a point about two inches below the navel in the centre of the body). Why would you want to do that? A straightforward answer is that keeping some focus on the body sensations helps to keep the practice grounded, reduce the risk of headaches from exerting yourself too much, and reduce the risk of mind-wandering (strange as it sounds, this does work for most people!). A deeper - and somewhat more esoteric-sounding - answer is that 'energy flows where attention goes', and by paying attention to the tanden you encourage the body's vital energy to gather there; that's a good idea, because the tanden is a 'safe' place to collect energy, whereas if it roams free around the body you can get strange physical side effects such as spontaneous movements, and if it goes up to the head you can get really bad headaches. (What's this energy stuff? That's a huge topic in its own right that I've written about previously, so check out that article if you're curious. Again, it's something that sounds very mysterious when you first encounter it, but is something that we can learn to experience in a very concrete, tangible way in time.) Perhaps the deepest interpretation of the instruction to put the question into your belly, however, is to take it completely literally. What could I possibly mean by that? Well, this is a tricky thing, and probably requires a certain amount of direct experience of the fabricated nature of perception before it'll really make much sense, but bear with me for a minute. Where do you think your thoughts? (Take a moment to test it out - think some thoughts, and see where they are.) Most people have a general sense that thoughts happen in their head, because we think with our brains, right? On the other hand, thoughts are not physical objects like tennis balls or pizzas - they don't weigh anything, and they don't have a size or shape. (In a minute I'll describe a way of exploring this in meditation.) So does it really make sense to say that thoughts have a location? We can perhaps talk about the physical location of the electrical activity in the brain that science tells us correlates with our subjective experience of thoughts, but in meditation we care primarily about what we can experience directly, not what fMRIs tell us. (Another clue that our sense of thoughts being located in the head is only a fabrication, not 'how things are', is that the impression that thinking lives in the head is not a universal human experience. Many cultures have instead associated thoughts with the heart - my teacher Leigh Brasington has commented that at the time of the Buddha, the brain was thought to be simply the 'marrow' of the head, while everything interesting happened in the heart centre, and although I can't track down the reference now I'm pretty sure I remember reading about the first Tibetan monks to be studied scientifically, who laughed uproariously when the scientists started attaching electrodes to their heads rather than their chests.) Something that sounds totally impossible at first, but which can become clear through practice, is that our sense of the spatial location of our thoughts - or even the spatial location of the sense of 'me' - is just another fabrication, like everything else, and with sufficient training we can actually learn to move it around. In a previous article I've mentioned a very common experience that comes up as people move more deeply into non-dual perception, where the sense that awareness has a 'centre' falls away entirely, and awareness is experienced as non-local rather than emanating from a particular point in space. But we can also learn to move that sense of locality around - so 'I' can experience 'myself' as being centred in my head, my heart, my belly, or even somewhere else entirely. (Some teachers recommend trying to put your sense of self outside the boundaries of your body - like on the far wall - as a fun exercise.) In any case, it's certainly true that we can learn to shift our sense of where our thoughts are taking place, and if we consciously shift the koan to the belly, this has two advantages: we get the energetic benefits of focusing in the belly that I mentioned above, but also we don't have to deal with the 'splitting' of attention that's required if you normally feel the questioning happening in your head. (Shifting your sense of centre from the head to the belly also has a number of other benefits - in a future week I'll be writing an article on hara cultivation which will address some of that, so stay tuned!) In the long run the question can come to permeate the whole body and even the whole environment ('grass and trees, fences and walls') - and again, I now mean this 100% literally in terms of one's felt sense of experience, as opposed to some poetic metaphor about how 'the truth is all around us'. Investigating thoughts If you'd like to explore this for yourself - which I would highly recommend - we can do this very directly in a kind of analytical meditation, of the sort commonly found in traditions like Mahamudra. I'd suggest taking a chunk of time to settle the mind before starting to look at thoughts, using whatever samadhi or just-sitting practice works well for you. Thoughts are slippery beasts, and it's a very fine line to tread between 'looking at thoughts' and 'engaging in thinking' - it's often easier to quieten down the mind first, then deliberately introduce specific some thoughts to work with. When you're ready to investigate thoughts, here are some questions you can investigate. Any one of these can be explored for many meditation sessions, or you can play with a mixture of them to see what catches your interest most keenly.

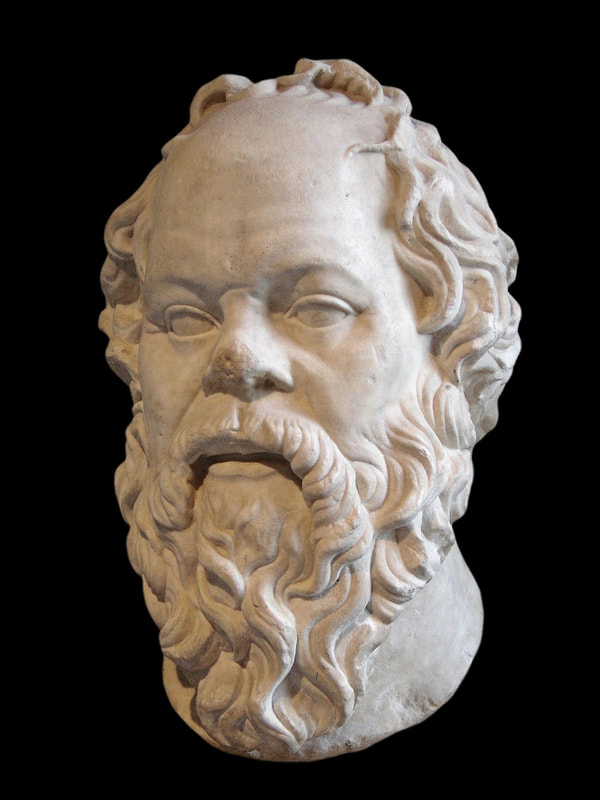

It's likely that sooner or later you'll reach the point of recognition that thoughts - and mind itself - are totally unfindable, without any kind of substance at all, and yet they're not non-existent either - when you're having a thought, you know you're having a thought. Analysis can take you no further into this apparent paradox - so at this point, simply rest in the paradox itself, the sense of the simultaneous presence and unfindability of thought and mind. Rest there and allow yourself to marinate in this sense of ungraspable presence. There's nothing more 'you' can do at this point - just keep out of the way and let the practice work on you. Happy hunting! How radical questioning can save us from self-deceptionImage from Wikipedia, courtesy of user Sting; Portrait of Socrates. Marble, Roman artwork (1st century), perhaps a copy of a lost bronze statue made by Lysippos; CC BY-SA 2.5. Socrates was a Greek philosopher from Athens who lived in the 400s BCE - roughly the same period of time as the historical Buddha - and is widely regarded as one of the founders of Western philosophy. It's fair to say that the way we think about things even today is shaped in large part by Socrates (and those who came after him, like Plato and Aristotle). And, in many ways, the work of someone like Socrates is a more natural fit to the modern Western mind than Eastern figures like the Buddha, Bodhidharma (the semi-legendary founder of Zen) or Hakuin (one of the most important Japanese Zen masters in the Rinzai Zen lineage).

Despite the great gulf in time and space between Socrates and Bodhidharma, however, there's an aspect of Socrates' work which dovetails beautifully with the essential project of Zen - peeling away our false beliefs about who we are, what life is and what it means to be happy. Shortly before his death, Socrates famously said 'The unexamined life is not worth living' - but how should we examine our lives? The Socratic method Socrates was deeply interested in truth - but not just any old truth, a certain kind of truth. Socrates was interested in how to life the good life - how to be a good person, what it meant to live a life of virtue and meaning. He was relatively uninterested in the work of the Natural Philosophers (a kind of forerunner of modern-day scientists), who could tell you what something was made of and how it worked, but not how to live a good life. And he was deeply critical of the Sophists - those who studied the arts of debate and persuasion, but in a rather mechanical way; a Sophist could teach you how to convince someone to agree with you, but not whether you actually should! (We only need to look at the world of politics to see plenty of finely honed debating skills employed for the sake of personal gain rather than the flourishing of humanity.) Socrates could see the people around him pursuing their busy lives, doing this and that, each searching for happiness in their own way - but often struggling, suffering, chasing the wrong things, looking for happiness in places that clearly weren't satisfactory to them. (The historical Buddha made exactly the same observation, of course.) And so Socrates started to inquire into truth itself - how we can know something to be true, and what it means to make decisions from a position of wisdom rather than ignorance. The method he came up with for doing this - the famous Socratic Method - looks like it would have been pretty annoying to be on the receiving end of! Picture the archetypal annoying four-year-old child, who just won't stop asking 'But whyyyy?' - except that the people Socrates was questioning didn't generally have the option of saying 'Because mummy and daddy said so, now it's time for bed.' Here's a typical example, lifted wholesale from John Vervaeke's lecture on Socrates. Socrates would come up to somebody and say "Well, what are you doing here?" "Oh, I'm in the marketplace!", his unwitting victim would reply. Socrates: "Well, why are you in the marketplace?" Victim: "Well, I'm purchasing something!" S: "Well, why are you purchasing something?" V: "Well, I want to get these goods!" S: "Well, why do you want these goods?" V: "Because they'll make me happy?" (Now the claws come out.) S: "Oh, so you must know what happiness is?" V: "Well happiness is pleasure, Socrates, I guess! And these things give me pleasure!" S: "But is it possible to have pleasure and still find yourself in a horrible situation that you really dislike?" V: "Well of course, Socrates, that's possible!" S: "Oh, so then happiness isn't pleasure! You're being coy with me! Tell me, tell me, what is happiness?" V: "Oh it's, you know, it's getting what's most important to you!" S: "Well that means that you have to have knowledge. Is it any kind of knowledge?" V: "Well no, it's the knowledge of what's important!" S: "What's truly important? Or what you only think is important?" V: "I guess what's truly important, Socrates!" S: "OK, so, what's that knowledge of what's truly important called?" V: "I guess that would be wisdom, Socrates!" S: "Oh, so, in order to find happiness, you must have first cultivated wisdom! Tell me how you cultivate wisdom and what wisdom is..?" V: "AAAAARRRRRRGGGGGGHHHHHHHHH!" (This last exclamation signifies that Socrates' latest debate partner has fallen into a state called Aporia, literally 'lacking passage', i.e. 'no way to move forward'. Compare this with the Zen koan from the Mumonkan: 'How can you proceed on further from the top of a hundred-foot pole?') 'All I know is that I know nothing' and Great Doubt Socrates is often misquoted as having said 'All I know is that I know nothing,' and taken in that light, we might see Socrates' method as a kind of cruel one-upmanship, a way of showing how much cleverer he is than you by tying you up in knots of confusion, tripping you up with your own words. But that's not really what he's up to. A better translation of his famous saying is 'What I do not know I do not think I know' - and anyone familiar with Zen might recognise the resonance with its concept of Great Doubt. What Socrates is pointing to is that, generally speaking, we lack secure foundations for what we think we know - and yet we act as if it's a sure thing. We pursue what we believe will make us happy, all too often failing to realise that it isn't actually working. Essentially, we deceive ourselves - and it's this self-deception that Socrates is trying to overcome. When we arrive at the point where we no longer think we know what we actually don't know, we throw off the shackles of false, limiting beliefs about who and what we are, and we gain the capacity to open to what's really going on, in all its mystery and wonder. We can see exactly the same dynamic going on in another koan from the Mumonkan: One night Tokusan went to Ryutan to ask for his teaching. After Tokusan's many questions, Ryutan said to Tokusan at last, "It is late. Why don't you retire?" So Tokusan bowed, lifted the screen and was ready to go out, observing, "It is very dark outside." Ryutan lit a candle and offered it to Tokusan. Just as Tokusan received it, Ryutan blew it out. At that moment the mind of Tokusan was opened. "What have you realized?" asked Ryutan to Tokusan, who replied, "From now on I will not doubt what you have said." This koan symbolises our tendency to rely on others - we often believe what we do because we heard it from someone else; we approach teachers to receive the wisdom that we believe they hold and we do not. Here, Tokusan is pestering the master Ryutan with many questions, in the hope that if he just asks the right one, he will gain the missing piece of knowledge that Ryutan has been concealing from him, and will finally become enlightened. Unwilling to go out into the darkness (presented as physical darkness, but an allegory for the intellectual darkness of not-knowing) all by himself, he again turns to the teacher to offer him a light. But at the crucial moment, Ryutan snatches the light away from him, and Tokusan is forced to confront the darkness in a moment of wordless surprise. As it happens, Tokusan was ripe for awakening, and this sudden dislocation out of the comfort zone of knowledge and certainty was enough to catapult him not just into darkness but all the way through the darkness into the light of awakening. Overcoming self-deception Why do this at all? Why question everything, especially if the result is to arrive at the uncomfortable-sounding place of Great Doubt? Because it turns out that the way we decide what's relevant to us - and hence what informs our decision-making - has nothing to do with whether or not it's true, and thus our capacity for self-deception is limitless. And only by noticing this startling disparity can we start to train ourselves to see more clearly and accurately - to make relevant what is true. Our minds categorise perceptions according to their 'salience'. Right now, you probably aren't paying attention to the sensations in your right foot - although after reading this sentence, maybe you are! Your right foot suddenly became salient because I called attention to it; previously, it wasn't remotely salient, so it wasn't part of your experience at all. We've talked many times before about how our experience is fabricated - our minds select which particular stimuli out of the available soup of sensory information are going to be woven into our direct experience in any given moment. And this is a really good thing - if it didn't happen, we would immediately be overwhelmed. Think about a time when you've been in a noisy environment surrounded by too many conversations and you can't pick out the one you're trying to focus on - and now imagine that you could never focus on anything, never select any particular piece of information out of the sea of events. Doesn't sound much fun, does it? It turns out that salience is highly adaptive. Maybe you've heard of the yellow car phenomenon - normally you don't see yellow cars much at all, until you start thinking about buying one, and suddenly it seems like half the world is driving yellow cars! Yellow cars became significantly more salient when you started thinking about buying one, and so now you're noticing every single one, rather than mostly ignoring them. Unfortunately for us, many of our sources of salience are not particularly helpful. We learn a lot of what to pay attention to and how to behave from the people around us - and it's fair to say that we aren't living in a particularly enlightened society. But we're also constantly bombarded by advertisements and other messages from people who have made a life's work of studying the manipulation of salience - people who know how to make a catchy slogan or earworm, something that your mind just won't put down once it's found its way in. And so our salience is constantly hijacked by what other people are telling us to think, believe, feel and desire. We believe what the media tells us to believe (or our alternative, non-mainstream news sources, if we're so inclined - but either way it's the same mechanism), we want the things that the people around us want, we do the things that everybody does, and because everybody calls this 'happiness' we do too, even if on some level we can tell it isn't quite working for us. And this is how we can deceive ourselves. It's extremely difficult to believe something that we know to be false - try telling yourself that you're actually a small green tomato and see how well that works, even if you try really hard - but we can bias our sense of salience in whatever direction is most convenient for us, regardless of whether that bias has any grounding in truth. If we decide that someone is unkind, we start to notice every little unpleasant thing they do - all the time gathering evidence to justify our belief - whilst simultaneously ignoring the times when they don't act that way. And, of course, notice that we don't even have to do this deliberately - the input of salience into our experience is pre-conscious, so we aren't necessarily even aware that we're seeing the world through a tinted lens. The Socratic method - and Zen practice - are designed to explore the way we experience reality - what we perceive, why, and whether our perceptions are as accurate and helpful as we believe them to be. Working with a partner and trying an actual Socratic dialogue is a really interesting exercise, but if you'd like to keep things within the remit of Zen practice, a good question to bring into your koan practice is 'What do I know for certain?' So don't delay - experience Aporia today! (This week's article is heavily inspired by John Vervaeke's magnificent lecture series, ***Awakening from the Meaning Crisis, in particular episode 4.) |

SEARCHAuthorMatt teaches early Buddhist and Zen meditation practices for the benefit of all. May you be happy! Archives

June 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed