Cutting through spiritual materialism

This week we're looking at case 27 in the Gateless Barrier, 'It is not mind or Buddha'. This koan is dear to my heart - Nanquan (who we've seen before in case 14 and case 19) is one of my favourite Zen masters, and this koan is one that I've spent a lot of time chewing over, and continue to do so.

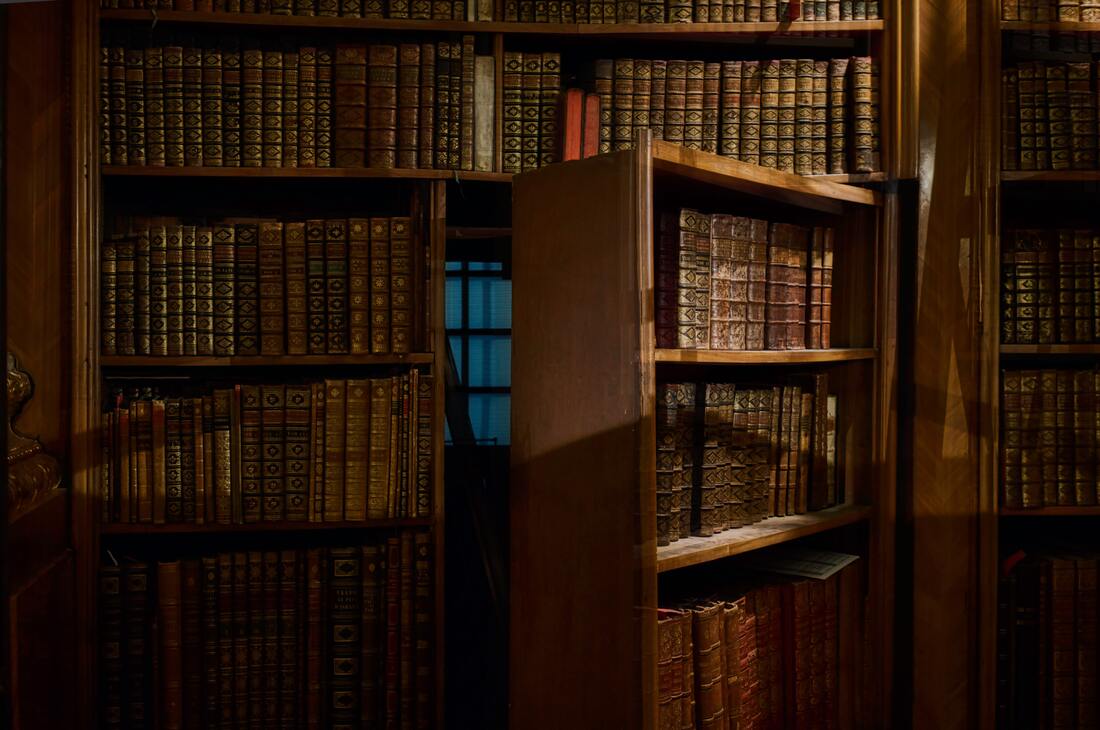

Why does it resonate with me so much? Because I see myself in the monk asking the question - I'm prone to the same mistake he is. Pursuing spiritual practice through acquisition I imagine that this monk was a pretty well-read fellow. He knew the classic Zen teachings, he probably had a few good discourses and poems committed to memory, he could explain the teachings forward and backward with ease. It's easy to approach spiritual practice this way. I love to read, and I have a vast and ever-growing library of books about Buddhism and other spiritual traditions. I enjoy getting into the details of historical disputes between this school and that one over some minor point of doctrine, and seeing how traditions over time have addressed the perennial issues that come up in spiritual circles through a wide variety of ingenious philosophies, metaphysical models and approaches to practice. I'm the kind of person who, if you ask me 'What does Buddha Nature mean?', will begin my answer with 'Well, it depends,' and proceed to rattle off several of the different ways the term has been used throughout history. I tend to grind my teeth when I hear someone say 'Oh, samadhi? That just means concentration,' because it's never quite that simple. Different teachers use terms in different ways, and what they're saying doesn't make any sense if you try to apply the wrong definition of a term in that context. Personally, I've found all this learning - all this collecting of knowledge - to be both inspiring and helpful for my own practice. I love finding out new things, and so it's a great joy when I come across a text describing something that I don't understand at all, because now I have a new project with a new discovery waiting for me at the end of it. Great stuff! The downside of all this is that it's easy to fool oneself into thinking that this gradual accumulation of knowledge and experiences is the 'point' of spiritual practice. Arguably the central principle in spiritual practice is letting go, not acquiring more. If we take too much interest in our growing trophy case of spiritual trophies, we're in danger of missing the point altogether. Let's get back to the koan and see how this can manifest. A crafty monk lays a trap Let's suppose this monk is familiar with Nanquan's ways - maybe he's even heard about the teaching outlined in case 19, that 'the ordinary mind is the Way'. A major theme in Zen is the idea of 'nothing special' - we don't have to go to some far-off place or transform our minds in some deeply mystical way. Strange experiences may come and go as we practise, but in the long run, the Zen ideal is to become utterly and completely ordinary, with no trace of 'enlightenment' remaining. Sometimes you see spiritual teachers who make a very big deal about how wonderfully special their experience is all the time - this is sometimes called the 'stink of Zen'. (My teacher's teacher, Shinzan Roshi, would sometimes hold his nose and say 'Stinky, stinky!' if someone was a little too impressed with themselves.) So this monk sidles up to his teacher and says 'Hey master, do you have any secret teachings?' Now, the monk is a smart cookie - he knows (because he's heard it from someone) that 'ordinary mind is the Way', so there's no secret teaching. He's expecting the teacher to confirm what he already knows, so he can go away feeling like a smarty pants and return to his complacency. On the other hand, he's also a collector of knowledge, and so, deep down, a part of him really wants there to be some kind of secret teaching. There actually is something called 'the secret teachings of Zen', and every time my teacher Daizan Roshi uses that phrase, my ears perk up. I want the secret teachings, dammit! The regular ones are boring, but the secret ones - that must be the really good stuff. So this question is a win-win situation for the monk. If Nanquan says 'no', the monk gets an ego boost - but if he says 'yes', SECRET TEACHINGS! The trap backfires Knowing that the promise of a secret teaching will really get the attention of this tedious bookworm monk, Nanquan says 'Yep, I have a secret teaching.' And it works - the monk is now hanging on his every word. 'Tell me, tell me! What is it, what is it?' Then Nanquan drops his bomb. 'It is not mind, it is not Buddha, it is not a thing.' (If Nanquan had been holding a microphone, he would have dropped it here.) Now, the koan doesn't tell us what happened next, so we don't know whether the monk had a great awakening or was simply thrown into confusion. But, speaking as someone who's had the rug pulled out from under me by Zen masters on more than one occasion, I can imagine at least some of what might have been going through the monk's mind at this point. Before we get into that, though, we should take a look at what Nanquan's reply actually means.

As I mentioned above, in case 19 Nanquan told Zhaozhou that 'the ordinary mind is the Way'. We might conclude from that that the object of Zen practice is to understand this 'ordinary mind' fully - and when we do, we'll know how to practise the Way and be free from suffering. But now he's saying nope, it ain't that - and, by doing so, he's undercutting the monk's expectations pretty severely. It's like the monk has been learning to play tennis for the last few years and his teacher has suddenly said 'Tennis? You're never going to play tennis.'

Now Nanquan goes a step further. In the Zen context, the word 'Buddha' is typically a shorthand for the principle of awakening itself, as opposed to a reference to the historical Siddhartha Gautama. Indeed, many koans begin with a student asking 'What is Buddha?' (see e.g. case 18 or case 21). But now Nanquan is saying nope, it ain't that either. This second part of the answer doubles down on the first part - not only has Nanquan rejected the 'ordinary mind' answer, but now he appears to be rejecting a basic pillar of Buddhism!

This last one is translated in different ways by different teachers. Thomas Cleary has 'It is not a thing,' as given above. Katsuki Sekida has 'It is not things' - Chinese doesn't have true plurals like English does, so you can make a case either way. Guo Gu has 'not a single thing', which calls back to Huineng's poem which I mentioned in the discussion of case 23 (the third line of that poem is sometimes given as 'Originally there is not a single thing'). Whichever way you translate it, though the meaning is the same. Nanquan is saying that the deepest truth of Zen is, ultimately, not any 'thing' in particular. As soon as you pin it down and say 'Oh, it's this', you've gone wrong. What is it like to be enlightened? In last week's article we looked at a description of awakening from the early Buddhist tradition - disillusionment, the fading of desire, liberation. When we encounter a model like this - which promises a radical transformation of the way we experience the world - it's natural to get a little uneasy about the whole thing. People will start to ask questions like 'But what's that going to be like?', or finding interpretations of the words that sound really bad ('Wouldn't it be boring if you never felt desire? I like desire!'). The problem is that it's impossible to say what it'll be 'like' to be awake, because it isn't 'like' anything in particular. It's a bit like asking 'What is it like to be alive?' - no matter what answer you give, it doesn't really capture what's going on. (The second most annoying thing in Zen is when a teacher says something smug-sounding like 'As soon as you start to talk about it, you've already gone wrong.' The most annoying thing in Zen is when you realise that they were right.) The next temptation lurking in the shadows is to turn 'no thing' into a fixed thing. 'Oh, I know this one, there's no fixed answer to it.' This is a kind of meta-strategy, a way of dealing with the mystery by throwing up our hands and saying 'No point, it's a mystery'. But that doesn't work either - and a good teacher will call you on it if you try. There's a story I heard once (I couldn't find the reference, sorry - if you know it, please leave it in the comments) about a student who tried to deal with his teacher's questioning with a wise, lofty response - 'Oh, you can't lay hand or foot on it' - at which point his teacher grabbed him by the nose and said 'Well I can lay a hand on this!' So what the heck are we supposed to do with this? It seems like all our options are cut off at this point. We can't say it's like something, but the mean old teacher will pinch our nose if we say we can't say it's like something - what's left? Well, one thing we can take from this teaching is that any time we find ourselves landing on one particular thing - a meditation technique, a philosophy, a way of being - as 'it', we can be certain that we've gone wrong. That's not to say that those things aren't useful! Meditation techniques can be hugely useful - this website is devoted to sharing them, after all, and I wouldn't be doing that if I didn't think there was value in it. The point is rather that if you find yourself thinking something like 'Ah, when I'm enlightened, I'll never have to deal with xyz any more' or 'I need to remember to do abc every day because that's what enlightened people do', that should be a warning sign that you've started to turn your practice into just another 'thing' to attain - and in doing so, you've missed the mark. If you'd like to work with this koan in your own practice, a pithy version of it is 'Not mind, not Buddha, not things - what is it?' If you figure it out, maybe you can write a book about it...

0 Comments

Finding peace in every situationThis article is the concluding part of our exploration of the Buddha's second discourse, which we started last week - if you'd like some context (not to mention the first half of the text), you might like to go back and check that out.

In the first part, we focused on anatta - the teaching on not-self, or non-self - which is the primary theme of the discourse. However, the Buddha goes on to introduce two more important concepts, anicca (impermanence/inconstancy) and dukkha (unsatisfactoriness/unreliability), and then tie those two and anatta together into a scheme that's become known as the Three Characteristics of Existence - a fundamental pillar of early Buddhist insight practice. He goes on to say what the consequences of a sufficiently deep exploration of the Three Characteristics might be - and it's pretty life-changing. So let's get into the text! Impermanence Having explained the basic idea of anatta to the monks (see last week's article for details) and invited them to explore the principle thoroughly, the Buddha then begins a question-and-answer session which he uses to introduce the other two characteristics. We begin with anicca. What do you think, mendicants? Is form permanent or impermanent?” “Impermanent, sir.” The Pali word anicca is usually translated as 'impermanence', although it also has a sense of 'inconstancy'. So this covers both things which may hang around for a while but don't ultimately last (like an ice cream melting at room temperature), and things which appear to be consistent but are prone to vanishing unexpectedly (like my internet connection). On one level, it can seem screamingly obvious that things are impermanent, no matter what scale we look at, and we may be tempted to think 'Yeah, impermanence, so what?' We know that civilisations rise and fall, friendships and governments (and prime ministers) come and go, bodily sensations change from moment to moment. And yet sometimes the impermanence of the world can really take us by surprise. I started a new job recently, having moved there from one which really wasn't working out for me, and after a settling-in period I'm really starting to enjoy it. Then I found out that there are changes coming which could potentially be really inconvenient for me. In the moment when I was given the news, I felt something akin to betrayal - I've finally got my job sorted out, how dare it go and change on me? Maybe you've experienced something similar, when you'd finally got all your ducks in a row, only for something unexpected to mess the whole thing up again. In the specific quotation above, the Buddha is essentially claiming that all form is impermanent - that is, all material things. We can look at this both in terms of ourselves, where 'form' refers to the physical body, or to the material universe in its entirety. Whatever we examine, we won't find anything which is not subject to coming and going, beginning and ending, birth and death, rise and fall. As I said last week, don't just take the Buddha's word for it (or mine)! Check it out for yourself. Find the most permanent, reliable, consistent physical things you can. Are they still going to be like that a year from now? Ten years? A hundred? A million? A billion? Some things change slower than others, but I've yet to find anything that doesn't change at all... but like I said, don't take my word for it. Unsatisfactoriness The Buddha continues: “But if it’s impermanent, is it dukkha or sukha?” “Dukkha, sir.” The Pali word dukkha is most commonly translated as 'suffering', but that's an unhelpful translation in this context. What the Buddha is getting at is better rendered as 'unreliable' or 'not a dependable source of happiness'. (Dukkha is here contrasted with sukha, which is usually translated as 'happiness' or 'joy'.) He's not saying that 'because everything changes, it all sucks'. Ice cream changes, but I still like it if I eat it quickly enough that it doesn't turn into a goopy mess (but slowly enough that it isn't frozen solid either - navigating the impermanence of ice cream is a tricky business). What the Buddha is saying is that impermanent things are not 100% reliable - precisely because they'll change on you. My job is great... until it changes in a way that I don't like. My internet connection is awesome, until it has an unplanned outage and I can't watch videos of baby goats when I want to. Again, this is something we should check out for ourselves. We can pretty easily thing of unsatisfactory things which are not sources of happiness, but most of us have go-to things which can pretty reliably brighten our day. But is that always true? If I eat some ice cream, I may feel a bit happier for a while - but if I keep eating ice cream, does it continue to produce happiness consistently? (I can assure you it does not.) Non-self Now we return to last week's theme: “But if it’s impermanent, dukkha, and perishable, is it fit to be regarded thus: ‘This is mine, I am this, this is my self’?” “No, sir.” Last week, Buddha suggested that, no matter what aspect of ourselves we examined, we wouldn't find anything which we could entirely control, so that we could have it just the way we want it all day every day - and, therefore, there was no aspect of our experience which could really be called 'me' or 'mine'. This is a high standard, but that's the point - as we discussed last time, we tend to feel that we have some 'essence', some essential 'me-ness', which really is permanent and dependable, and so the Buddha is challenging us to find anything at all in our experience which could possibly meet that high bar. Now he's backing up his previous claim that there's nothing meeting those criteria with an argument which both works on the logical level and gives us something to investigate in meditation. If we really, truly, carefully and thoroughly examine every aspect of material form in our experience, and 100% of it turns out to be subject to changing and vanishing outside of our control (anicca), then it can't possibly be a dependable source of happiness (dukkha), and as such is not fit to be regarded as 'me' or 'mine' (anatta). Boom. Of course, the material world isn't the only place where an 'essence of me' might be hiding - what about the mental world? Extending this analysis to the remaining aggregates The Buddha continues: “Is feeling permanent or impermanent?” … “Is perception permanent or impermanent?” … “Are choices permanent or impermanent?” … “Is consciousness permanent or impermanent?” “Impermanent, sir.” “But if it’s impermanent, is it suffering or happiness?” “Suffering, sir.” “But if it’s impermanent, suffering, and perishable, is it fit to be regarded thus: ‘This is mine, I am this, this is my self’?” “No, sir.” As I noted last week, I've written previously about the Five Aggregates, so check out that article if you aren't familiar with them. But in a nutshell, the remaining four aggregates represent the aspects of our experience which are purely mental - our preferences (whether we find something pleasing, displeasing or meh), our perceptions (the way we see and understand the world; our concepts), our choices (intentions, impulses and other mental activity relating to the sense of will), and our consciousness (our ability to know what's going on). Each of these, the Buddha says (of course, by now you know you've gotta check this out for yourself), is going to turn out to be impermanent and inconstant; consequently, each will turn out to be not a reliable source of happiness; and, as a result, none is a suitable hiding place for this elusive 'essence of me'. On that bombshell... This is starting to sound like bad news. For one thing, it's starting to sound like there's a good chance that I don't actually exist. But leaving aside that whole existential crisis, there's a bigger problem - if we can't find anything constant or reliable, anything that's a dependable source of happiness, then what the heck are we supposed to do? Where do we hang our hat, so to speak? Maybe Buddhism really does say that everything sucks after all! Well, let's see what the Buddha goes on to say. Maybe it'll help. (Maybe not. It's hard to tell with these old texts sometimes.) Seeing this, a learned noble disciple grows disillusioned with form, feeling, perception, choices, and consciousness. Being disillusioned, desire fades away. When desire fades away they’re freed. When they’re freed, they know they’re freed. They understand: ‘Rebirth is ended, the spiritual journey has been completed, what had to be done has been done, there is no return to any state of existence.’” This is dense, so let's take it a line at a time. Seeing this, a learned noble disciple grows disillusioned with [the aggregates]. A central idea in Buddhism is that we spend most of our time caught up in an illusion - an illusion of permanence, of dependability, of essential natures. We believe that we inhabit a solid, reliable, logical, predictable world, and if we can just arrange our affairs correctly then we'll be happy for the rest of time. And despite all the evidence to the contrary - all the bumps and bangs of life, all the unexpected let-downs and sudden upheavals - on an unconscious level we cling desperately to this comforting, but ultimately illusory, belief. When we really examine the Three Characteristics in our experience, over and over again, we gradually become convinced that the world isn't really the way we thought it was. Everything changes; nothing is totally dependable; nothing is fixed. Being disillusioned, desire fades away. As we come to this new understanding, our relationship to what's going on changes. Previously, we believed on some level that we could get lasting happiness 'out there' if we could only collect all the Pokemon (or whatever). Having seen that that kind of strategy is never going to work - not because we're not trying hard enough, but simply because that isn't what reality is actually like - the impulse to reach out and fiddle with everything until it's just to our liking fades away. No matter what's going on in our life, no matter how good our material circumstances, we know we'll always be able to find something wrong with it - so why worry? (Hopefully it goes without saying that this doesn't mean that people in extreme poverty or lacking basic human needs should just suck it up and stop complaining. But if you're agonising over whether your jacket pocket is big enough for the iPhone 14 or whether you'd be better off with the 14 mini, you can probably relax. I just bought a 13 mini, so whichever one you get you'll have a fancier phone than me.) When desire fades away they’re freed. And this, just this, is the end of our struggle. Gone is the subtle itch at the back of our minds that says 'Yes, but wouldn't it be so much better if..?' Reality simply is what it is, and it's fine - even when it sucks. It might sound paradoxical, but there's a kind of 'meta-OKness' which is available in any situation, whether that situation is pleasant or unpleasant. As our practice is developing, it's likely that we'll each find a limit beyond which we lose sight of that 'OKness', but over time, as our realisation deepens, it becomes available in a wider and wider range of circumstances. Then, as Marcus Aurelius said, it is possible to be happy even in a palace. (I have a student who reliably objects at this point that they don't just want to feel 'OK' all the time - they want to have fun! Well, I'm not saying you can't have fun, or that you'll be limited to one emotion for the rest of your life - quite the opposite, actually. What I'm saying is that, even in the most excitingly fun life imaginable, aspects of it are unavoidably going to suck if we continue to insist that the universe should line itself up to our satisfaction. If we can instead let go of the illusion that this would ever be possible, then our wellbeing is no longer dependent on things being arranged to our liking. It doesn't mean you have to give up ice cream if you like it, but if you order ice cream and they tell you there's none left, it won't spoil your evening any more.) When they’re freed, they know they’re freed. They understand: ‘Rebirth is ended, the spiritual journey has been completed, what had to be done has been done, there is no return to any state of existence.’” 'What had to be done has been done' is the standard form of words that we find in the Pali canon when a monk wants to announce to the Buddha that he or she has become an arahant - a fully awakened one. Thus, what the Buddha is saying is that if you take your exploration of these Three Characteristics far enough, you too can go all the way, and become free. And, in fact, that's exactly what happens next. The Five Guys wake up That is what the Buddha said. Satisfied, the group of five mendicants were happy with what the Buddha said. And while this discourse was being spoken, the minds of the group of five mendicants were freed from defilements by not clinging. If you saw my articles on the Buddha's first discourse (part 1, part 2), you might remember that that discourse was also given to his five ascetic friends, and at the end of the discourse one of them (Kondañña) attained stream entry, the first stage of awakening. This time around, all five guys go all the way to arahantship. Nice! (Maybe that's why they decided to go into business together.) So perhaps you've attained arahantship just by reading these articles - if you have, please leave a comment to let me know. But if not, at least you have the next best thing - the framework of the Three Characteristics, which you can use to explore your subjective experience in your meditation practice. Sooner or later you'll find your own way to 'disillusionment', freedom from desire, and ultimately a lasting peace of mind. May you, too, do what has to be done, and find freedom in this very life. Spoiler alert: no!'Who am I?' is the quintessential spiritual question. It's been a favourite topic of sages, mystics and contemplatives for thousands of years, and it comes up on this website quite a bit as well!

This week (and next), we're going to take a look at what is traditionally considered to be the second discourse given by the historical Buddha, Siddhartha Gautama - the 'discourse on not-self' - in which the Buddha outlines his take on what's going on, and gives us some tools to explore it for ourselves. If you've been following this blog for a while, you can treat this article and next week's as a sequel of sorts to the two-part series on the Buddha's first discourse (part 1, part 2). That discourse gave us the bones of early Buddhism - the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path. The present discourse now puts flesh on those bones, taking a look at the nature of the self (which we'll consider this week) and inviting us to explore the all-important Three Characteristics (which will be next week's subject). First things first - what do we mean by 'self' anyway? It might seem a bit pedantic or scholarly to start with definitions - all I can say is that the maths degree I studied at university has clearly left its mark on me - but in this case at least it's pretty important, because the concept that the Buddha was exploring which we usually translate as 'self' is probably pretty different to what you or I mean by the term in casual usage. In the time of the Buddha, the prevailing world view was quite different to the one we have today. Time was seen as fundamentally cyclic - you would live, die, be reborn, and more or less the same things would happen over and over, a bit like a cosmic Groundhog Day. Many spiritual teachers of the day taught that each person possessed an atman (Sanskrit; the Pali is atta). The atman was seen as something akin to a 'soul' in Christianity - an enduring 'essence' which survived the death of the body and went on to be reborn into the next life. A commonly held belief was that each atman was a small piece chipped off a larger divine being or essence, Brahman, and that the 'goal' of spiritual practice was to reunite one's atman with Brahman and thus escape the wheel of rebirth into the material world of suffering. Now, in the 21st century Western world, there's a good chance that you don't believe in a spiritual essence that lives somewhere inside you and migrates from body to body across lifetimes. (Maybe you do, in which case you can skip to the next section!) However, I'm going to suggest that even modern audiences can meaningfully engage with this teaching if we reframe it slightly. Whether you believe that there's anything after this life or not, most people would agree that it feels like there's a 'me' here having this experience - and, furthermore, that that 'me' doesn't really seem to change, despite all the experiences in our lives. It feels very much to me like whatever is looking out of my eyes is the same 'me' that was riding my BMX bike around with my friends when I was nine years old, or the 'me' that was doing maths exams a little over twenty years ago. We often feel this 'sense of self' especially strongly when in a difficult situation - for example, when someone calls your name in a crowded room, and then maybe follows it up with 'This is all your fault!' It tends to be quieter and more in the background when we're alone in nature. Nevertheless, it's pretty pervasive, and is at the root of our sense of identity - the sense that there's an identifiable 'me' here which has some kind of fixed essence, some 'me-ness' which makes me who I am, regardless of whatever else might change in my life. So whether or not you believe you have an atman which is trying to find its way back to Brahman, you can hopefully relate to this 'sense of self' in your own experience. (If not, the rest of this article isn't going to make a lot of sense!) The Buddha's discourse on non-self (anatta or anatman) Now that we've set up some basic concepts, let's see what the Buddha has to say about the self. We're going now to Samyutta Nikaya 22.59, the Discourse on Anatta. Thus have I heard. At one time the Buddha was staying near Baraṇasi, in the deer park at Isipatana. There the Buddha addressed the group of five mendicants: “Mendicants!” “Venerable sir,” they replied. The Buddha said this: “Mendicants, form is not-self. For if form were self, it wouldn’t lead to affliction. And you could compel form: ‘May my form be like this! May it not be like that!’ But because form is not-self, it leads to affliction. And you can’t compel form: ‘May my form be like this! May it not be like that!’ 'Form' here means 'material form', i.e. 'the body'. What the Buddha is saying is that - whether or not you do have some kind of 'essence' - your body can't be it. Why not? Because if your body were really 100% 'you' then you should have complete control over it - you should be able to decide how you want it to be, and that should be all there is to it. I don't know about you, but my body doesn't work like that! If I had complete control over it, I'd change one or two things - get rid of the asthma, add a bit of muscle tone, shed a few pounds of useless but remarkably stubborn fat, that kind of thing. Clearly, I don't have absolute control over my body. Much as I'd like to, I can't stop myself getting ill - my body does that by itself. Sometimes I'm physically clumsy when I'd much rather be precise and skilful - no matter how hard I concentrate, my limbs refuse to move with the precision I desire. On the other hand, it isn't that my body is 100% disconnected from 'me' either. It certainly seems that I'm able to make choices and influence what happens to my body over time. I do an exercise routine pretty consistently, and it definitely helps to keep me reasonably fit. When I choose to eat a lot of unhealthy food, my body gets fatter, and when I make different choices, it gets slimmer (although it gets fatter much more easily than it gets slimmer - something else I'd change if I could!). So the relationship between 'me' and 'the body'/'my body' is not one of absolute control; but equally, it isn't that there's no relationship at all either. My behaviour affects my body (and vice versa). My body is clearly an important aspect of who I am - but the relationship is one of mutual influence rather than absolute control. It's more like the relationship we might have with a close friend - we can make suggestions, but sometimes our friend has other ideas. The discourse continues: Feeling is not-self … Perception is not-self … Choices are not-self … Consciousness is not-self. For if consciousness were self, it wouldn’t lead to affliction. And you could compel consciousness: ‘May my consciousness be like this! May it not be like that!’ But because consciousness is not-self, it leads to affliction. And you can’t compel consciousness: ‘May my consciousness be like this! May it not be like that!’ Readers familiar with early Buddhism will recognise the scheme of the Five Aggregates here. I've written extensively on these previously, so go and check out that article if you don't recognise them. In brief, though, the Buddha is saying that every other aspect of who we are is just like the body - the things we like and dislike, the concepts we use to understand the world, the choices we make (whether intentional or impulsive), and even our basic ability to recognise what's going on around us. Just like the body, all of these are clearly important aspects of who we are - and, just like the body, they're neither entirely within our control nor entirely beyond it. So what does that leave? Who actually are we? Sometimes, people say that the Buddha taught 'no self', but as you can hopefully see from the above, that isn't what's going on at all. It isn't that there's 'nobody here at all' - we aren't helpless or powerless, and what we do in the world really matters. At the same time, though, we aren't fixed in the way that we usually take ourselves to be - we're much more 'process' than 'thing'. Small glimpses, many times Insight practice can sometimes come across as being a bit 'heady' or intellectual, and up to this point what I've written could come across as a logical, rational argument intended to persuade you to believe something about the nature of the self. But simply changing an abstract, intellectual belief is not at all what this practice is about. Here's what the Buddha says: “So you should truly see any kind of form at all — past, future, or present; internal or external; coarse or fine; inferior or superior; far or near: all form — with right understanding: ‘This is not mine, I am not this, this is not my self.’ Any kind of feeling at all … Any kind of perception at all … Any kind of choices at all … You should truly see any kind of consciousness at all — past, future, or present; internal or external; coarse or fine; inferior or superior; far or near: all consciousness — with right understanding: ‘This is not mine, I am not this, this is not my self.’ The aim of insight practice is to change the way you experience the world, not just the way you think about it. The invitation here is to explore your moment-to-moment sensory experience, lightly holding the question 'Who am I?' as you do. What's going on right now? Who are you in this moment? Is your sense of self tied up in your body, your thoughts and emotions, something else? Is it always the same, or does it change from one situation to the next? Can you pin down 'Aha, this bit is me!', or is it a moving target? Can you find anything fixed or solid - anything like an 'essence'? Or can you see clearly for yourself, in your immediate experience, that it's all processes and interactions, all a complex web of relationships, with nothing solid to be found anywhere? Why do this? The exploration of the self has been central to spiritual practice for millennia for good reason. We tend to approach the world from the standpoint of our 'self' - we judge and measure what's going on as it relates to us, as it provides us with opportunities for loss or gain, pleasure or pain and so on. Because this sense of self provides the foundation for our whole world view, a lot of mental energy has to go into keeping the self propped up, advertised to those around us and defended from whatever might threaten it. Unfortunately, this gives rise to inner conflict - we try to relate to ourselves as if we were something fixed, ignoring the reality that everything is in motion all the time. We take what should be free-flowing water and freeze it into ice, then wonder why it's no longer able to flow smoothly with the twists and turns of life's river. As we turn the light of awareness onto our 'self', the ice begins to melt, and we come to a different relationship with what's going on - one that's based in flow. We come into a dynamic intimacy with life, flowing effortlessly with the bends in the river, ebbing and surging as the situation requires. May your ice melt soon! Like Einstein said, it's all relative...

This week we're looking at case 26 in the Gateless Barrier, 'Two Monks Roll Up a Screen'. At face value, it's pretty straightforward - the master asks his monks to open a window, and one of them beats the other one to it. Simple! But, as usual, there's more going on than meets the eye. So let's dive in!

The Eight Worldly Winds Gain and loss are one of four pairs which together comprise the Eight Worldly Winds - eight sets of conditions in conventional life which have the power to blow us this way and that. If we arrange the pairs so that they rhyme, the full set of eight is:

Looking at our own lives, we may well be able to see instances of these winds in operation. Our brains are hard-wired to be deeply aversive to loss, and less strongly drawn toward gain (we will, in general, work much harder to avoid a loss than to acquire a gain). Similarly, all living creatures have a natural tendency to move toward pleasure and away from pain. Humans are social creatures, and so we're also sensitive to interpersonal forces. Some people live for the praise of those around them, while others find it vaguely uncomfortable to be put in the spotlight. For many people, blame is immensely unpleasant (particularly when the blame is unfair!), but for others, criticism can be a source of motivation, a challenge to be overcome. And on a broader level, we each have a certain reputation - perhaps positive, perhaps not so much - and we can be very sensitive to how that reputation might be affected if we make a fool of ourselves in public. On one level, then, we can look at this koan as a straightforward example of these winds in action. The master asks for the window to be opened, and two monks respond - but one is faster than the other. Should we interpret the master's comment as a compliment to the faster monk (who thereby gains his master's praise, and potentially an enhanced reputation too, all of which will no doubt feel rather pleasant), and a criticism of the slower monk (who thereby loses out on the opportunity to impress the teacher, and perhaps develops the negative reputation of being slow off the mark - likely to be rather unpleasant, perhaps even painful)? However, Zen masters are rarely so crass as to offer praise and blame for their own sake. Generally speaking, if you see something in a koan that looks like a competition between two monks, it's a setup of some kind - there's something deeper going on. So perhaps, instead, the master is saying this as a test - to see if his monks have developed sufficient equanimity that his words of praise and blame don't have that effect on them. In the long run, one of the beneficial effects of this practice is to make us much less susceptible to the Eight Worldly Winds - to give us the ability to hold fast in the centre of our own experience, letting worldly conditions come and go without unnecessarily disturbing our peace of mind. And so this koan can be a test of our own equanimity. What do we see in the words? If we were the quicker monk, would we be feeling pleased with ourselves right now? What about if we were the slower one? Gain and loss as a matter of perspective Albert Einstein probably didn't actually say 'it's all relative', but his monumental theory of Relativity (a profound scientific theory about the nature of space-time) is based on the fundamental insight that things look different depending on where you're standing. And while Einsteinian relativity doesn't have a whole lot of bearing on a meditation practice, it's also true for Zen practitioners that what we see depends very much on how we're looking at it. We often look at potential gains or losses as isolated events - you lose £100 betting on the horses or you don't, you gain that new job or you don't. But if we look a bit closer, there's more going on than that. For one, what might appear to be a 'gain' before the fact may turn out to be a mixed blessing once we have it, and likewise for a 'loss'. A couple of years ago now a friend of mine broke up with his long-time partner - the loss of a relationship which had deeply shaped his life for many years. However, this painful event served as a catalyst for many positive changes in his life, and now he's much happier than he was before. For me, I got a new job in 2011 which I thought was going to be great, but in fact turned out to be a total nightmare! (There's a traditional story about a farmer which I mentioned in a previous article on the Eight Worldly Winds - check it out if you don't know the one I mean, it's a classic. The story, that is, not my article - although the article isn't bad either, in my humble opinion!) Even this, though, supposes that any given event can ultimately be classed as 'a gain' or 'a loss'. Another, perhaps richer, way to look at it is simply as change - impermanence in action. Change has many consequences, some obvious, some not so much. The shadows of our choices I used to write music, although I haven't done it seriously for a while now (this meditation thing has expanded to fill all of my available spare time!). I would often find myself reluctant to add a melody to my tunes; when I listened to the chords and harmonies, I could imagine all the potential melodies that could exist over them, and I found that I was reluctant to cut off all of that potential by fixing on one specific, actual melody. I actually liked the music I produced, but most other people who listened to it would say 'Not bad, needs a tune though.' Choices are like that too. When we commit to something, we exclude all of the possible alternatives. As the monk opens the window, the room gains the light, but loses the darkness. (Perhaps some of the monks in the hall were thankful for the light, but others had been enjoying the peaceful darkness.) There is no gain without loss, no choice which is simply one thing and nothing else, no change which doesn't simultaneously exclude all other possible changes in that moment. It can be very interesting to spend some time reflecting on the web of cause and effect in our lives, to see how even innocuous choices can take us down paths very different to those we might have ended up on had we made a different choice in the beginning. Who gains, who loses? One final perspective shift worth exploring is the (appropriately Zen-like) question of who gains and loses. It turns out that questions of gain and loss depend a lot on where you're standing - just like Einstein said! (I promise I'll stop trolling the scientists in the audience now.) Suppose my next-door neighbours and I decide to swap houses. From my perspective, I've gained their old house and lost mine. From their perspective, they've lost their old house and gained mine. From the perspective of the street as a whole, however, very little has changed - some of the contents of the street have moved around a bit, but there are still the same number of houses and people, still the same amount of stuff, just redistributed a little. If I take my water bottle to work with me, I don't generally think that my house has lost a water bottle, although you certainly could look at it that way. Coming back to science again for a moment, science tells us that energy can neither be created nor destroyed, just changed from one form to another. In the same way, from a broad enough perspective, nothing at all can really be gained or lost - it just moves around and changes form from time to time. Even life and death - some of the biggest events in our lives on the personal level - are just another day of business as usual when viewed from the perspective of the whole universe. We can choose to see death as the loss of a specific life, or as just another change in the larger matrix of universal life. Neither perspective is 'truer' than the other - both are equally true, and equally one-sided. Coming back to the koan This koan is an invitation to consider gain and loss deeply. What do they mean to us? What are their ramifications? What aspects of the gains and losses in our lives have we overlooked or not fully considered? How do the difficulties in our lives appear to us when viewed from another perspective, perhaps a broader one? And are we able to find wisdom, compassion or both by shifting to a different perspective? May you find peace even in the midst of the Eight Worldly Winds. |

SEARCHAuthorMatt teaches early Buddhist and Zen meditation practices for the benefit of all. May you be happy! Archives

June 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed