Earth, water, fire and air aren't just for the Ancient Greeks...This week's article is the third in a series on the Satipatthana Sutta, the early Buddhist discourse on four ways of establishing mindfulness. Check out the first article in the series if you missed it, because it provides an introduction to the discourse and puts the practices contained therein into context, as well as looking at the first few practices in the first section of the discourse, focused on mindfulness of the body. In the second Satipatthana article we continued working through the mindfulness of body section, looking at the deconstructive 'parts of the body' technique. This week we'll take that deconstruction further still, by looking at the Four Elements. (I've actually written about the Four Elements relatively recently, but this time we'll be looking at the original text, so hopefully you'll get a slightly different flavour from the material,) So buckle up, and let's get into it!

The Four Elements, as described in the discourse Again, monks, one reviews this same body, however it is placed, however disposed, as consisting of elements thus: ‘in this body there are the earth element, the water element, the fire element, and the air element’. That's it for the description of the core practice. Pretty simple! Basically, whatever's going on with the body, the practice is to regard it in terms of what are sometimes called the Four Great Elements - earth, water, fire and air. But what does that mean exactly? The Four Great Elements are seen as the constituent aspects of physical reality in early Buddhism. Each represents a different quality:

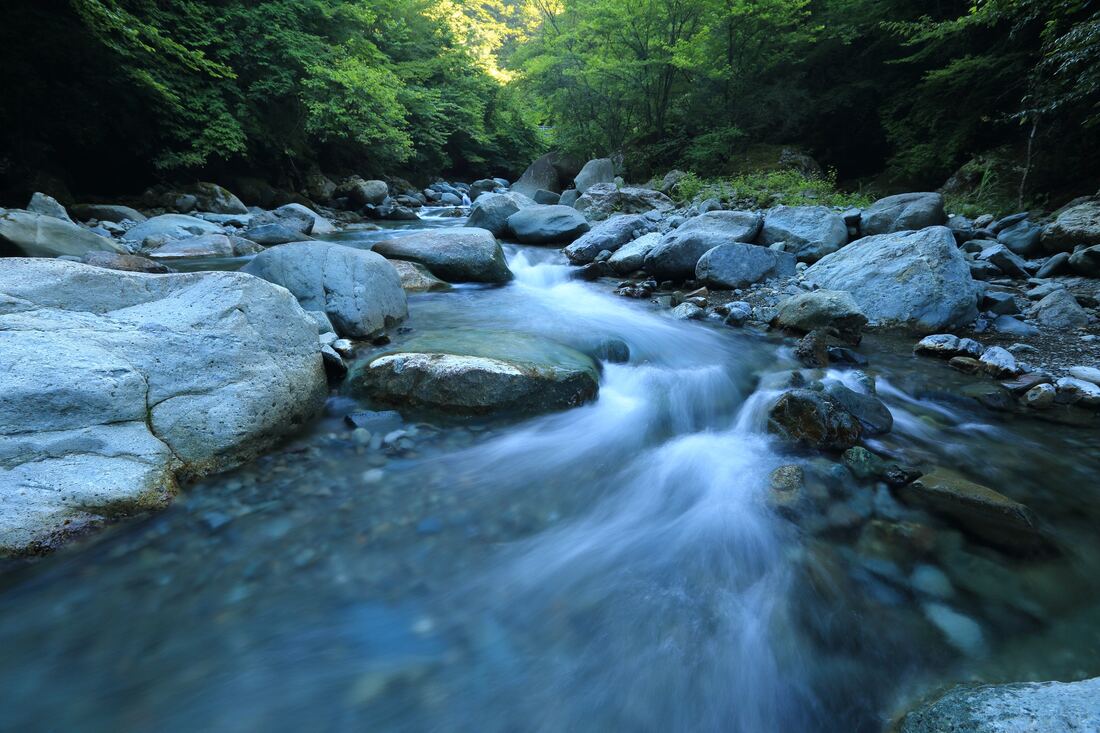

Before we go further, it may be helpful for some readers to clear something up. If you're of a scientific bent, I'm not asking you to throw away your Periodic Table, and I'm not suggesting that a dry twig secretly 'contains fire' somehow, or that this can be demonstrated by setting it alight to 'release the fire element'. The types of 'elements' we're talking about here are not like carbon, copper and plutonium. Although the Pali word 'dhatu' is often translated as 'element', it also has the sense of 'aspect' or 'characteristic', and that's how we're being invited to look at reality here. The point of this exercise is not to replace a modern scientific understanding of the types of atoms which form the physical structures of the universe. Rather, the purpose of this practice is to take the deconstructive process that we applied to the body last time, by looking at it in terms of its parts, and to go one step further - not even looking at identifiable parts of the body now, but breaking everything down into these four primal aspects of materiality: solidity, liquidity/cohesion, temperature and movement. But why would we want to deconstruct our experience to such a primitive level of analysis? Excellent question, thanks for asking. Whenever we encounter something through one of our senses - sight, hearing, smell, taste, touch or thought - we tend to conceptualise it; that is, we form an idea about what we're sensing, often represented in shorthand in the form of a label ('chair'). Hanging off that label is a whole host of associations - for example, ideas about how the object can be used ('good for sitting, or possibly for fighting off a room of attackers if you're Jackie Chan'). Those associations may then bring up impulses to take certain actions ('let's sit down, that would be nice'), or trigger more thoughts ('y'know Jackie Chan really made some great movies back in the day, I ought to watch Rush Hour again'), and so our minds spin on and on into the process of mental proliferation - unless we've meditated enough to be able to let thoughts go when they arise rather than simply being swept away. An interesting point about this process is that we tend to put a lot of credence in our thoughts very readily. In a sense, it seems to us that our concepts about reality actually are reality. It feels like we're seeing and hearing an objectively real world, and any sensible observer in the room with us would experience basically the same thing, doesn't it? In fact, when another person perceives something differently to us, it often comes as a surprise, and can even lead to arguments, unless we can 'agree to disagree'. The power of deconstructive meditations like the four elements (and last time's parts of the body) is that they can show us the extent to which we're experiencing our conceptualisation of what's going on, rather than some objective Truth of the universe. In a nutshell, if we change the labels, we change our experience. This is because the labels, or concepts, are the building blocks of the stories we tell ourselves about what's going on, and if we change the labels, we change the building blocks, which means we ultimately change the story. I talked about this at length in my previous article on the Elements, so check out the section titled 'Change the label, change the story, change the experience' in that article if you'd like to read more. For today's article, let's get back on to the discourse. Right after the description of the practice, the Buddha includes his inevitable simile, which clearly emphasises the deconstructive nature of what's being suggested. The inevitable simile Just as though a skilled butcher or [their] apprentice had killed a cow and was seated at a crossroads with it cut up into pieces; so too [one] reviews this same body.... (continue as above). As my teacher Leigh likes to point out, this simile was evidently written at a period in Indian history before cows were considered sacred! Unlike the simile of the bag of different types of rice from last time, this one is short and sweet. We have a butcher and an ex-cow, who for some reason are sitting at a crossroads (if you have any idea of the significance of the crossroads, please let me know!). But whereas in the previous simile we had a long list of distinct, identifiable contents, this simile simply says that the cow has been reduced to 'pieces'. The deconstruction has gone far enough that it's now difficult to say whether we're looking at a section of leg or whatever; we're simply seeing a heap of nameless bits. The most we can say is that the bits have some kind of size (extension) and solidity, some kind of moisture or cohesion, and so forth. The refrain, and suggested avenues of exploration for this practice Again, as before, we have the same 'refrain', the 'chorus'-like section that follows each practice in the discourse. In this way, in regard to the body [one] abides contemplating the body internally … externally … both internally and externally. [One] abides contemplating the nature of arising … of passing away … of both arising and passing away in the body. Mindfulness that ‘there is a body’ is established in [oneself] to the extent necessary for bare knowledge and continuous mindfulness. And [one] abides independent, not clinging to anything in the world. That too is how in regard to the body [one] abides contemplating the body. As with the body scan, you could look at 'internally' and 'externally' in terms of what you feel beneath the surface of the body versus what you feel on the surface. However, it can also be very interesting to look at the Four Elements as they're found in the external world. Notice the solidity of the ground beneath your feet, the moisture in the air on a misty day, the temperature of the sun beating down, the movement of birds in the sky and fish in a river. Going outdoors is a great asset here; humans like to construct environments to live in which are comparatively safe, orderly and sterile compared to the vibrant chaos of nature. Then, when you've got a sense of the Four Elements all around you, notice that the Elements in you are the same as the Elements around you. Both you and the world around you have aspects of solidity, liquidity, temperature and motion. We sometimes think of ourselves as very special, separate creatures, making a distinction being 'man-made' and 'natural', but at the level of the Elements we're totally continuous with nature, just as much a part of the natural world. Reflecting on the sameness of yourself and your surroundings can be a powerful way to dissolve the felt sense of separateness between yourself and everything else, and can be an interesting way to explore anatta, non-self/essencelessness, one of the Three Characteristics which form the core of many insight meditation techniques from the early Buddhist tradition. The refrain also explicitly suggests another of the Three Characteristics, anicca, impermanence or inconstancy. We're invited to notice the experience of the Four Elements arising within the body and subsequently passing away - impermanence at work. In the same vein, we can use the Four Elements to explore the third and final of the Three Characteristics, dukkha, unsatisfactoriness. One way is to notice that the Elements are often experienced as unsatisfactory - for example, maybe there's not quite enough Fire in your environment (i.e. you're too cold), or too much (too hot). Maybe your breakfast porridge doesn't have the right balance of Water element - it's too sticky, or too runny. And so on. It can be especially interesting to pair this one up with impermanence, and notice how even a balance that seemed pretty good at first rapidly loses its sheen; that refreshing breeze soon turns into an unpleasant, chilly draught. We can also use the Elements to work with the dukkha in our experience, following the theme of 'change the label, change the story, change the experience' - again, I described that approach in some detail in my previous article on the Elements, so check that out if you're interested. That's a lot of options! Yes, it is. But that's OK - you don't need to do all of them right now! If one or more of these approaches sounds interesting, then great, but there's no obligation to try every single variation that I'm suggesting. If you were tempted to do that, I'll point out that these are just some of the variations that I've personally explored in my own practice - you can also find other teachers offering many more. The point of these meditations is not really to try each approach once to get a tick in the box and be able to say that you've 'done' Four Elements. The point of all of these meditations is to provide methods by which you can explore reality, so that in the long run you'll develop insight into what's going on in your experience. Which method is best? The one that interests you enough to do it! Is it better to use one method, or several? Again, whatever holds your interest. There's definitely something to be said for a period of focus on a single technique rather than doing a new meditation every day - as the saying goes, it's better to dig one deep well rather than many shallow ones - but insight meditation can be a fun, creative exploration of reality, and that exploration can take many forms. If you're continuing to delve deeper and deeper into what's going on then it doesn't really matter whether you're using one technique or several; conversely, if you want to use your meditation practice to sit in a happy bubble disconnected from the world, never encountering anything that might trouble you, you can do that just as easily with your one favourite technique as you can by jumping around a dozen practices. For me, exploring the unknown is what got me into this practice in the first place, and it remains my greatest joy, so I'm totally unapologetic in offering many ways to engage with today's topic, or indeed anything else. If you're more of a 'One True Technique' person, good for you. (Sometimes I wish I was - it would make life simpler.) On the other hand, if you're more naturally inclined to creative exploration, but feel that you need someone's permission before you can really dive in, then consider my permission granted - for whatever that's worth!

1 Comment

Opening to life's natural flow

This week we're looking at one of my favourite koans in the Gateless Barrier, case 19, 'The normal is the Way'. It features two characters who we've seen before, one several times - Zhaozhou showed up in case 1 (giving a puzzling answer to a question about Buddha Nature), case 7 (telling a monk who was asking for a Zen teaching to go and do the washing up), case 11 (where he tested the realisation of two hermits), and case 14 (where we also met his teacher Nanquan for the first time).

In today's story, however, Zhaozhou has not yet become the profoundly realised Zen practitioner that we've seen in those previous koans. Rather, he's earlier in his practice career, asking perfectly reasonable questions and getting frustrating answers from his teacher, just like the students in the other koans. Perhaps it's a sign of my own insecurities as a practitioner, but I like that we get to see this younger, less experienced (and perhaps more relatable) Zhaozhou, sitting alongside other koans where he's at the height of his considerable powers. We also find his teacher, Nanquan, in a kind and patient mood. (If you've read case 14, you'll recall that last time we met Nanquan he cut a cat in half to stop his monks arguing!) Zhaozhou has a string of questions - but rather than shout at him or hit him with a stick (as we might imagine Yunmen might have done), Nanquan does his best to give a kind of explanation. Of course it isn't totally straightforward - it would hardly make for a good koan if it were! - but I like the fact that Nanquan is trying to lead Zhaozhou forward gently. I've always responded better to teachers who take that approach with me! So let's get into the story and see what's going on. After the last few which were pretty short, this one gives us a fair bit to work with, so we'll take it one piece at a time. What is the Way? When Buddhism arrived in China, it encountered the native philosophy/religion of Daoism. The word 'Dao' translates as 'Way' or 'Path'. There are many such Ways; each profession is said to have its own Dao (the Way of pottery, the Way of accountancy), each animal has its own Dao (the Way of a tiger is quite different to the Way of a sheep), and so on. Encompassing all of that, however, is the Great Way, the Way of Heaven, the universal Dao. Daoist texts such as the Daodejing and Zhuangzi are concerned with pointing to this Great Way so that Daoist practitioners can learn to live in harmony with the universe, and thereby attain peace. According to some sources I've read, Buddhism was initially regarded as a form of Daoism by the Chinese, and Daoist language found its way (no pun intended) into Chinese Zen (aka Chan Buddhism). Some of the Daoist terminology is somewhat repurposed in Zen, so we should be careful about placing too much emphasis on the similarities - it's not really accurate to say that Daoism and Zen are 'the same', although they share much in common. Nevertheless, there's a strong family resemblance, and most Zen folks will find much to appreciate in Daoist writings (and vice versa). So Zhaozhou opens this exchange by asking his teacher 'What is the Way?' This is one of those questions like 'What is Buddha?' or 'What is the meaning of Bodhidharma's coming from the west?', which is really used symbolically - we could equally well say 'How should I practise Zen?', 'What is Zen?' or 'What is the meaning of life, the universe and everything (and don't say 42)?' It's an invitation for the teacher to offer whatever teaching suggests itself in the moment, as opposed to asking about a specific point of practice or doctrine. The normal mind is the Way Nanquan replies that the 'normal mind' is the Way. (In other translations we find 'ordinary mind'. Same difference.) Readers familiar with case 18 should recognise this theme straight away. It's in the same spirit as 'Just breathe naturally' - on the face of it, the answer seems to suggest that there's nothing at all that needs to be done; one should simply do whatever comes naturally. But, as we explored in that article, if that's the case, why do we need to practise at all? And is it really OK to do whatever comes to mind? Seems like that could be a recipe for trouble! I won't rehash the whole of the previous article here - go back and read it if you want to see a more detailed explanation. The basic point here is that there's a distinction between the habitual mind, which is plagued by reactivity and fettered by negative learnt patterns of behaviour, and the natural mind, aka the normal or ordinary mind, which has let go of that reactivity and conditioning, and can instead respond freely and spontaneously to whatever arises, coming from a place of generosity, compassion and wisdom rather than greed, hatred and delusion. Can it be approached deliberately? So far so good - this 'normal mind' thing sounds great. But Zhaozhou has an obvious question - how are you actually supposed to get to this 'normal mind'? Is there a method for the cultivation of the ordinary mind? Again, I really like this question. It's very human. I've read quite a number of Zen (and Daoist) texts and come away thinking 'Wow! That sounds amazing!' But then, when the initial thrill has worn off, there's the inevitable question: 'OK, so now what?' Unfortunately, Nanquan's answer probably isn't going to spark joy for most of us. If you try to aim for it, you thereby turn away from it So here's the central problem. The ordinary mind, by definition, responds spontaneously to circumstances. There's no method for that - the moment you reach for a method, you've already moved away from a spontaneous reaction which is wholly tailored to the situation. Contrary to the stereotypes of what it means to 'be Zen', there's no single strategy that will magically resolve all of life's difficulties. To make matters worse, though, the very search for such a strategy gets in the way of the natural mind. By looking for a one-size-fits-all way of being in the world, we're simply trying to replace one set of conditioned responses with another - a little like trying to learn good information to replace the bad information we previously had. Zen is asking something much more radical of us - that we let go of strategies completely, and take each moment as it comes. As it says in the Daodejing (chapter 48): In the pursuit of learning, every day something is acquired. In the pursuit of Dao, every day something is dropped. Less and less is done Until non-action is achieved. When nothing is done, nothing is left undone. The world is ruled by letting things take their course. It cannot be ruled by interfering. If one does not try, how can one know it is the Way? Zhaozhou is perhaps getting a little frustrated at this point. It seems like Nanquan's answer didn't really help at all. He started by saying 'just behave naturally', and when Zhaozhou asked 'OK, but how do I learn to do that?', Nanquan is saying 'You can't learn to do it - even trying to learn to do it is already moving you in the wrong direction.' And so, not unreasonably, Zhaozhou is wondering how this is supposed to work. If there's no method, if you can't act deliberately in order to reach the Great Way, then how will you ever know if you've made it? Once again, we're back to the central problem: if there's nothing to do, what's the difference between that and never having practised? A less compassionate koan might already have stopped, leaving us to chew on 'The ordinary mind is the Way', or even 'If you try to aim for it, you thereby turn away from it.' Fortunately, Nanquan was in a compassionate mood that day, and so gives us more to work with. The Way is not in the province of knowledge, yet not in the province of unknowing. Knowledge is false consciousness; unknowing is indifference. This is a fascinating answer, because it cuts directly to the heart of the matter. Nanquan rejects both sides of the duality implicit in Zhaozhou's question. He says that the Way is not something that can be 'known' - but, at the same time, that doesn't mean it's 'unknowable'. 'Knowledge', he continues, 'is false consciousness.' In other words, when you 'know' something, you don't really 'know' it. Huh? Zen is full of sayings like 'mountains are not mountains, rivers are not rivers'. But of course they are - that's why we call them mountains and rivers! That's what the word means! But what the Zen folks are getting at is that the word 'mountain', or even the concept of a mountain that the word points to, is not the same as the actual mountain. In order to identify a mountain as a mountain, you move from the direct experience to a concept about the experience - and, in so doing, you reduce the specific, unique mountain that's in front of you to an element of a generic category of 'mountains'. More generally, as soon as we think about something we must, by necessity, separate ourselves from that thing. But if we simply allow ourselves to be in the experience, there's no need for that conceptual gap between 'me over here, thinking about the experience' and 'the experience over there'. To use a spiritual cliché, we become one with the experience. And Nanquan wants us to be clear that there's a difference between this 'being one with' and simple ignorance. 'Unknowing is indifference,' he says - obliviousness, inattention, lack of interest. The 'normal mind' that Nanquan wants us to find is absolutely not a matter of stopping caring or giving up on the world and just doing whatever comes to mind, no matter how harmful it is to ourselves or to others. We cultivate mindfulness for a reason! Indeed, in Nanquan's closing salvo, he reaffirms that the Great Way absolutely is something that we can align ourselves with, and there's a meaningful difference between the experiences of alignment and misalignment. It's just that the difference between the two is not a matter of knowledge, not a matter of having a particular idea in mind that separates you from all the dummies who have the wrong ideas. Rather, it's a way of being - letting go of the separation between us and the experience, and finding ourselves in a place which Nanquan describes as 'like space, empty and open' - no barriers, no separation, no obstacles. Simply the unfolding of experience. The flow state There's a clear parallel here with the 'flow' state described by psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, who spent a great deal of time studying the types of experience that people reported as being most enjoyable and most effective. His book on the subject is very good and surprisingly readable, but in brief, flow is a state characterised by the following:

As the second point notes, in flow there's no 'knowledge' in the sense that Nanquan means it - there's no gap, no split, no separation between you and what's happening. There's simply the unfolding activity. What Nanquan is suggesting is that the flow experience can increasingly become our natural state. We can learn to find our way into this 'ordinary mind' and then rest there, at first only briefly, but eventually for longer and longer, until it becomes our default way to be in the world. It's perhaps a little ironic that the flow state, which is considered rare and exalted in Western psychology, is regarded as the mind's 'ordinary' condition in Zen - but perhaps that's just a sign of how far out of step with the Great Way our modern society has become. One thing is for sure - the flow experience is rewarding enough that there's really no need for 'affirmation and denial', as Nanquan points out. When we're in flow, we're so fully engaged in the flow that there's no space to ask 'Wait, am I in flow yet?' - if you have to ask, you ain't there yet. But once you are, you don't need to ask any more. So don't delay - enter the Great Way today! 'Just as though there were a bag with an opening at both ends...'This week's article is the second in a series on the Satipatthana Sutta, the early Buddhist discourse on four ways of establishing mindfulness. Check out the first article in the series if you missed it, because it provides an introduction to the discourse and puts the practices contained therein into context.

In this article, we're going to dive straight in with the next practice in the first section - the parts of the body. (Those of you who are interested in which are the 'original' practices in the Satipatthana might like to know that today's practice is the only one in the first section to appear in all versions of this discourse, although the actual practice I'll be recommending is a little different to what's in the sutta.) The parts of the body practice, as described in the discourse Again, monks, [one] reviews this same body up from the soles of the feet and down from the top of the hair, enclosed by skin, as full of many kinds of impurity thus: ‘in this body there are head-hairs, body-hairs, nails, teeth, skin, flesh, sinews, bones, bone-marrow, kidneys, heart, liver, diaphragm, spleen, lungs, bowels, mesentery, contents of the stomach, faeces, bile, phlegm, pus, blood, sweat, fat, tears, grease, spittle, snot, oil of the joints, and urine.’ Lovely. What's being presented here is an exercise in deconstruction. We may typically think of 'the body' as a 'thing', a single object which goes about the world doing things. Here, however, the Buddha is inviting us to consider the body as an assembly of parts. Actually, it's more accurate to say 'a system of parts' rather than 'an assembly of parts' - an assembly could imply something static, like a structure made out of Lego bricks, whereas a system has more of a processual quality to it. And, indeed, the body has this quality of 'process'. Our nails and hair grow; when (if?) we clip them shorter, we don't typically look at the off-cuts in the bin and weep for the loss of part of ourselves. They'll only grow back and need cutting again anyway! As we continue to examine the body in this way, we can see more examples of the body's nature as a process, and we start to get a feel for the dynamic nature of the whole thing. And that's the gist of the practice - seeing the body in terms of its constituent parts, seeing the trees that make up the forest. Of course, there's a simile Followers of early Buddhism will be familiar with the many similes that the Buddha uses throughout the Pali canon to try to explain the Dharma in terms of everyday language for the time in which he lived. And this practice is no exception: Just as though there were a bag with an opening at both ends full of many sorts of grain, such as hill rice, red rice, beans, peas, millet, and white rice, and [someone] with good eyes were to open it and review it thus: ‘this is hill rice, this is red rice, these are beans, these are peas, this is millet, this is white rice’; so too [one] reviews this same body.... (continue as above). OK, we have a bag - well, the body is a kind of skin-bag, right? It's a big collection of stuff enclosed with skin. 'Skin-bag' is perhaps not the most attractive metaphor for the body, but it'll do for these purposes. So what's in the bag? All sorts of stuff! Hill rice, red rice, beans, peas, millet and white rice. And they're all mixed together. (Not a good storage system if you ask me.) But someone with good eyesight can look at this mixture of stuff and pick out the hill rice from the red and white rice, separate the beans from the peas and the millet, and so on and so forth. The point here is that at first sight the mixture in the bag appears as just one thing - 'the mixture' - with a bit of careful examination we can start to tease it apart into multiple constituent parts (hill rice, red rice and so on). In the same way, through careful examination of the body, we can come to relate to it in terms of its constituents, rather than as a monolithic entity. Note also that the bag in the simile has an opening at both ends (again, I'm not convinced this is a good way to store rice). Bodies have quite a few openings! If you had a rice bag with a hole at both ends, rice would fall out of the bottom hole every time you picked it up, and need to be replenished through the top hole. In much the same way, our bodies expel various bits and bobs over the course of a day, and some of that needs to be replenished by inserting new things at the top. So although the simile perhaps isn't the best advice for the long-term storage of food, it describes the body pretty accurately. The practice as written The main drawback with the practice is actually highlighted in the simile - we don't actually want to open up our skin-bag to review its contents with our eyes! As a result, there's likely to be a certain amount of imagination involved when taking the inventory of the body - I don't know about you but I'm certainly not hyper-aware of my spleen. In fact, in general I'm only aware of the innermost bits of my body when something is going wrong with them. Working with the list of body parts as given can make for an interesting contemplation practice. However, when doing insight meditation, it can be extremely helpful to work with what we can concretely experience with the five senses, rather than what we think or imagine might be going on. One of the foundations of Buddhism is the idea that we are fundamentally confused or deluded about what's going on in our experience, and so it can be very helpful to focus exclusively on what we can actually see, hear and feel for ourselves, temporarily stepping out of the world of thoughts, ideas and what we 'know' to be true about our experience in order to see what's actually there. With that in mind, let's take a look at a modern variant of the practice, which is very much in line with the spirit of 'deconstructing the body', but which focuses more on what we can feel directly. The body scan The body scan seems to have been developed in Burma during the colonial period, as part of a nationalistic effort to revive Buddhism within the country. (Buddhist scholar Ven. Analayo argues that the Burmese creators of the body scan were actually drawing inspiration from the 'mindfulness of breathing' practice earlier in this discourse, but I think it's close enough in spirit that it makes a good 'parts of the body' practice too.) Subsequently, the body scan was picked up by Jon Kabat-Zinn and incorporated into his Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction course, and as a result has found itself front and centre in many modern presentations of secular mindfulness. There's also a family resemblance with certain yoga nidra practices. Bearing all this in mind, it's no surprise that there are many, many different versions of the body scan. At their core, though, they all revolve around bringing our attention to the physical sensations of the body, one area at a time, and gradually moving around the body until we've covered the whole thing. The most important part is that we should feel what's going on in the body - not think about the body, not imagine what might be going on, not visualise the body parts, but tap into the physical sensations present, whatever they might be. (Actually, in some parts of the body, we might not feel anything at all! That's fine. Generally speaking, the body will 'wake up' over time and you'll get more and more sensation, but your experience in the moment is whatever your experience is - there's no right or wrong level or type of sensation to find when doing the body scan.) The major difference between all the different body scans is the route taken around the body. I was taught to start at the top of the head and spiral slowly down to the soles of the feet, scanning horizontal 'layers' of the body like an MRI scanner. I'm told that the Jon Kabat-Zinn version is similar, but starts at the feet and moves up to the head. My teacher Leigh's version starts at the top and works down but does the whole arm before moving on to the torso rather than jumping across horizontally. You may have learnt another version again. Ultimately, the route doesn't matter. What matters is the continuity of awareness, and - at least if you're interested in developing samadhi - the speed at which you move. But we'll talk more about that in a moment - for now, we have the standard 'refrain', which appears after every practice in the Satipatthana Sutta. The refrain In this way, in regard to the body [one] abides contemplating the body internally … externally … both internally and externally. [One] abides contemplating the nature of arising … of passing away … of both arising and passing away in the body. Mindfulness that ‘there is a body’ is established in [oneself] to the extent necessary for bare knowledge and continuous mindfulness. And [one] abides independent, not clinging to anything in the world. That too is how in regard to the body [one] abides contemplating the body. As I said, this is the same thing we had last time, so the same considerations apply. How should we interpret 'internally' and 'externally' here? We have a few options:

We also see again the explicit nod to the impermanence (anicca) practice. Body sensations come and go like everything else, so looking at the fine arisings and passings as you do the body scan is a good way to practice. The body scan also makes for an excellent non-self (anatta) practice. When you bring your attention to your forearm, you're making the forearm the object - if you're the subject and your forearm is the object, then I guess the body ain't you. Repeat for the rest of the body parts, and sooner or later you can't help but find the identification with the body lessening. (At which point you may want to ask 'So what exactly is the 'subject' here anyway?) And, of course, the body is also a good opportunity to contemplate unsatisfactoriness (dukkha). The body is often a source of unsatisfactory sensations, and even if it starts out feeling pretty good, if you continue to examine it for long enough that'll change. What about samadhi? In addition to using the body scan for insight, it also makes a good access concentration practice. The fact that you're moving around every few seconds makes the practice inherently more engaging than following the breath, so it can be easier to build up some sustained focus. The main point to watch out for is that you do continue to stay with the sensations from moment to moment, rather than simply observing the sensations in an area of the body and then switching off. I think of this as the 'tick-list' approach to the body scan - 'Yep, still got a left shoulder. Now, what am I doing this evening? Oh, time for the left upper arm. Still there, good. Right, tonight I think I'll watch that new series on Netflix...' The other key point is the speed of the practice. Doing a relatively swift body scan can be OK for insight, but will tend to be a little on the quick side to build up good concentration. My teacher Leigh Brasington recommends that you between 30 and 60 minutes on a body scan if you want to build up solid access concentration. Some guided body scans, including one by Leigh Brasington On my Audio page you'll find two shorter body scans - one is about 10 minutes long, the other 25. The 10-minute one is nice when you don't have much time, and can give you a feel for how the practice unfolds. The 25-minute version works well for insight, but is on the short side to be building up much concentration. If you're interested in concentration, my teacher Leigh Brasington has a 45-minute body scan on his website which is more suitable. It's worth saying that you might not like it much the first time you do it. If that's the case, then you should do it a lot! The body scan can often bring us into contact with aspects of our bodies (including unpleasant memories that we've 'buried' on the physical level) that we would prefer not to confront, but it's usually extremely helpful to bring some awareness to that very material. The only exception is in the case where there's a history of severe trauma, in which case body-based practices should be approached carefully and in collaboration with a mental health professional who can provide appropriate support. May your explorations of the body prove fruitful! Postscript: Should you use an audio recording or self-guide? This morning I got a question from a student about whether it's better to use an external guide (e.g. the audio recordings linked above), or to do it yourself. It's a good question; here's my answer. Personally, I think it's better to learn to self-guide. It's a bit fiddly at first because there are lots of instructions and it can take a while to learn a route around the body, but in the long run learning to self-guide means that you aren't dependent on having the audio file handy. Self-guiding is also a little more challenging in terms of maintaining mindfulness because you don't have an external prompt tapping you on the shoulder every few seconds (although see caveat below). In terms of the route, any route that encompasses the whole body will do - it doesn't have to be mine if you're already familiar with someone else's. I linked to my teacher Leigh's 45-minute version of the scan above, as well as my own 10- and 25-minute recordings; as mentioned, Leigh is interested in generating a reasonable level of samadhi (he finds the body scan good for developing access concentration) so it's understandable that he would want to take his time. For me, I was taught to teach the body scan in a Rinzai Zen context where the standard length of meditation is 25 minutes - which Leigh would regard as too short in general, because he sees 30 minutes as the bare minimum, and prefers an hour. And I run a lot of mindfulness sessions for beginners where 10-15 minutes is a more appropriate length of time. Once you have a route, it's relatively easy to tailor how long it takes - I suggest that you don't just move faster from place to place, but rather divide the body into smaller or larger sections. For example, if you want to take more time, you can take the upper arm in four sections - the outside (the side facing away from the body), the front, the inside (next to the body), and the back. If you don't have so much time, you can simply gently scan the whole upper arm all at once. You can even tweak the size of the body regions you're using as you're going through, if you find that it's taking too long (or not long enough). I suggest that your route is symmetric, though - so if you did the left upper arm in four parts, do the right upper arm in four parts as well. I mentioned a caveat in relation to the superiority of self-guiding. I used to be pretty hard-line about this, because I'd always found it vastly preferable to self-guide my own meditations. Generally speaking, guided meditations annoy me - I want to be getting stuck into the practice, so the guidance only serves to interrupt what I'm doing, and I don't like to be interrupted! But then toward the end of last year, when my Dad was very poorly, I found that my mind was so chaotic when I sat to meditate that there was no chance of being able to focus on anything without some kind of external support. During that period I took great comfort from working through Zen teacher Henry Shukman's series of koan practices on Sam Harris's Waking Up app - it was nice to have something new, but mainly I found it very supportive to have a kind, gentle voice in my ear throughout the sitting period. Since then I've been a lot more accepting of guided meditation - although I still think it's better to self-guide if the conditions allow for it. I hope this helps! Easier said than done!

It sounds like the setup for a joke - 'What's the difference between Buddha and three pounds of burlap?' But it's actually case 18 in the Gateless Barrier, a collection of Zen koans compiled in the early 13th century, and it's the subject of today's article. So buckle up, and let's try to make sense of this bizarre exchange.

What on earth..? I must admit, I haven't been looking forward to this one! The koan doesn't give us much to work with - there's no sense of a back story, and Dongshan's reply seems pretty meaningless on the face of it. Sometimes these pithy phrases are references to other well-known Zen stories, but that doesn't appear to be the case here. When I first came across this koan I had no idea what to make of it, so I spent quite a while looking up the commentaries of other teachers. I found pretty universal acknowledgement that this is one of the harder ones. In fact, quite a few of the 'commentaries' I read started with a vague attempt at an 'explanation' ('Maybe Dongshan was weighing out flax at the time?') and then go on to fill up many more paragraphs with unrelated 'Zen stuff'. By the time I'd finished reading the commentary, I'd often feel like I'd read a good Zen teaching - just not one that was particularly relevant to the actual koan! Another common device - which seems to be the last resort of commentators who don't quite know what to say, and I'll admit to having used this trick myself at times - is to say 'Ah, well, the function of this koan is to stir up doubt.' It's certainly true - many koans are designed to present seemingly impenetrable problems, as a way of inviting the practitioner to go beyond their analytical mind and 'interrupt the circuit of thought', as Wumen (the compiler of the Gateless Barrier) put it in his prose comment to the first case in the collection. But I think that's a bit of a cop-out too - critics of the koan method will often claim that koans are meaningless gibberish, but that hasn't been my experience at all. There's something of value in each and every koan, and if I can't make sense of a particular case yet, that's a sign to me that I have a blind spot in my practice, and thus an opportunity to discover something new. After sitting with this one for a while, I think I have an inkling of what's going on. Much like the previous case, I have a long way to go in terms of being able to embody the teaching myself, but I believe I can at least see the direction of travel, and that alone may be worth sharing. And even if it misses the mark in terms of this koan, at least I'll have produced a few paragraphs of Zen-related stuff as a result... The medium is the message Sometimes, a Zen master will respond to a question with an action, rather than a verbal response. We've seen this before in case 14, where Zhaozhou responded to Nanquan by putting his sandals on his head and walking out of the room. (If you don't know the story, go and read the article - it's a fun koan!) I'd argue that a similar thing happens in case 13, where the Zen teacher is caught out in a mistake, going for his food at the wrong time, and when he's challenged by the young monk Xuefeng, he doesn't stand around debating the point or making excuses, he simply returns to his room. In this case, I believe Dongshan is responding to the monk's question with an action - it's just that the action happens to be a verbal one. But it isn't what's being said that's important in this case so much as how he's saying it. When I was training as a meditation teacher, my teacher said something which has (ironically) stayed with me pretty much word for word ever since. He was describing the experience of teaching to a group of students, and how one's attitude and embodiment of the teachings was much more important than the specific words and phrases used to explain the mechanics of those teachings, and he recounted some advice given to him by his own Zen teacher: 'Two weeks from now, they won't remember a word you said; but they'll always remember how you were.' Certainly when I think back to some of the memories seared mostly strongly into my own mind, the specifics of the words exchanged are not always particularly clear, but the emotional tone of the encounter is crystal clear. So perhaps in this case the 'three pounds of burlap' are not so important - what matters is where Dongshan is coming from when he says it. But where's that? Spontaneity in Zen, and 'just breathe naturally' In Zen (perhaps more so than some other forms of Buddhism), emphasis is placed on the importance of naturalness and spontaneity. (Perhaps this is a sign of Daoism's influence on Zen.) Within my own Zen lineage, we have practices of 'spontaneous movement' which are meant to help us get in touch with a kind of innate, intuitive wisdom, rather than living purely from the place of our rational, reflective mind. As mentioned above, we can also see koans as a tool that can be used to break us free from our deliberate thinking and connect us with something deeper. But what does 'spontaneity' actually mean? One possible answer is 'just do what comes naturally, without worrying about it', but that doesn't seem terribly appealing. I'm sure we've all had the experience of taking the path of least resistance in a situation and subsequently regretting it - when I'm in an angry state of mind, for example, certain actions may suggest themselves to me which would be pretty dreadful if I followed through on those impulses. Another possible objection is that, if all we have to do is to do whatever comes naturally, then why do we need to meditate and do all this other stuff? What's the point of Zen if the ultimate message is 'just do what you were going to do anyway?' I'm reminded of my Tai Chi teacher, who is endlessly annoyed by the advice in some of the classic texts on Tai Chi, which say 'Just breathe naturally.' Take a room full of people off the street who've never done Tai Chi before, and the last thing you want them to do is 'breathe naturally'. Most people have very poor breathing habits (because we as a society collectively breathe inefficiently and unhealthily, and children learn their breathing habits from the people around them), and so need to be trained out of breathing that way. When we finally do let go of the awkward habits we've had up to that point, the resulting breath feels beautifully natural, and so from that perspective it makes total sense to say 'just breathe naturally'! Perhaps the distinction we should make, then, is between 'breathing naturally' and 'breathing habitually'. What we want is the natural breath, but what we typically get when we don't do anything special with the breath is instead the 'habitual breath'. It takes a deliberate process of training to 'unlearn' the habitual breath, until we finally arrive at the truly natural breath. There's even a period in the middle where we can consciously choose to breathe 'naturally', but as soon as we forget - as soon as our mindfulness slips - we go back to breathing 'habitually'. Eventually, though, the natural breath replaces the habitual breath (or, to put it another way, natural breathing becomes habitual), and there's nothing left to do. The same applies to the mind in Zen. As we'll see in the next koan in the collection, the 'ordinary mind' is sometimes said to be the totality of the Way - but, in just the same way, your 'ordinary mind' is not your 'habitual mind', or at least not at first. A considerable process of training and discipline is required to unlearn the mind's old habits before the 'ordinary mind' can become our everyday state. A method for learning to 'breathe naturally' As I mentioned above, many of us breathe in an unhealthy, inefficient manner, taking many breaths each minute and using only a tiny portion of our lung capacity. So how should we breathe? There are lots of breathing techniques and methods out there. Some teachers advocate breathing as slowly and deeply as possible, while some practices such as qigong and yoga pranayama breathe in very specific ways. One approach to breathing which is well supported by science is 'coherent breathing'. In a nutshell, the idea is to take five breaths per minute, breathing in for six seconds and breathing out for six seconds. It's called 'coherent' because when we breathe at a consistent pace (and, in particular, when each in-breath is the same length and each out-breath is the same length), the variability of our heart rate decreases (becoming 'coherent'). Decreased heart-rate variability has various beneficial effects, including enhanced brain function. Taking five breaths per minute also has the effect of balancing the parasympathetic ('rest and digest') and sympathetic ('fight or flight') branches of the nervous system. This might seem like an odd thing to want to do from a meditative point of view - don't we want to relax and de-stress? But actually the ideal condition for a meditation practice is a state which is balanced between stillness (parasympathetic) and clarity (sympathetic), where we aren't just quiet and relaxed to the point of drowsiness and dullness, but we actually also have a bright, clear awareness of what's going on in the present moment. So give this a go. You can use one of the recordings on my Audio page (inspired by this one, credit where it's due) to time the in-breath and out-breath. As you're breathing, pay attention to where and how you feel the breath, too. When the body is relaxed, you should find that the breath starts in the abdomen, then fills up the chest, and maybe you even get some movement at the top of the chest, around the clavicle area. As you breathe out, the process reverses - the clavicle, the chest, and then the belly. There's no need to force this to happen, but if you find that your breath is only in one part of the body - perhaps just the chest, or maybe just the belly if you've previously learnt abdominal breathing - see if you can allow the body to relax until you can ultimately feel movement in all three areas. I suggest practising this every day for a few months. If you have a daily meditation practice already, you could use the first few minutes of your meditation time to breathe in this way - I'm currently using the first 20 minutes of my hour-long morning sit, for example. Although it might feel at first like you're 'losing' meditation time, you should find that coherent breathing puts you into a good place from which to begin the meditation - in essence, you get some mindfulness and concentration 'for free', just by preparing the body in the right way. (I like to think of this as configuring the hardware correctly before starting to run the software, but then I'm a giant nerd.) Give it a go and see what happens! If you need further persuasion, check out this Guru Viking interview with Charlie Morley, especially the section starting at 34:36 and then going into a guided coherent breathing session at 46:10. Coming back to the koan A monk asks Dongshan, 'What is Buddha?' In other words, what is the Way? How should I practice? What are we trying to do here? What's this Zen thing all about? Dongshan replies not by telling him the answer, but by showing him to answer. Dongshan is resting his his ordinary mind, breathing naturally, totally alive to the moment. Rather than engage his thinking mind to find a way of describing this natural state to the monk, Dongshan reacts spontaneously - in this case, by saying the first thing that comes into his mind, 'Three pounds of burlap!' The words are unimportant - he could have said 'Rice in the pan', or 'It's sunny today', or broken into song. The point is the immediacy and freshness of the response - no tired Zen cliche, no lengthy lecture on formal practice. Just a momentary flash of activity, here and gone again in the blink of an eye. That's where Zen points us - to a place where each moment is fresh, alive and brimming with vitality. May you find this place for yourself, and then share it with others - just like Master Dongshan. |

SEARCHAuthorMatt teaches early Buddhist and Zen meditation practices for the benefit of all. May you be happy! Archives

June 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed