Opening our hearts to difficult peopleIn last week's article we took a look at loving kindness, the first of early Buddhism's four heart-opening practices. Usually those practices are called the Brahmaviharas (see last week's article for the origin of the name!), but actually in the early Buddhist discourses they're far more often referred to as 'the heart's limitless release', and they're also referred to as apramana - 'boundless' or 'immeasurable'.

This 'limitless' quality is also clear from the way the practices are described in the early texts, e.g. in this excerpt from Majjhima Nikaya 127: And what is the limitless release of the heart? It’s when a mendicant meditates spreading a heart full of love to one direction, and to the second, and to the third, and to the fourth. In the same way above, below, across, everywhere, all around, they spread a heart full of love to the whole world — abundant, expansive, limitless, free of enmity and ill will. (Emphasis mine.) The implication here is that these qualities extend equally in all directions - and to all beings. Yes, even that one person who drives you up the wall. Which sounds pretty difficult! So this week we'll take a look at how we might go about this. But first, I'll say a few words about the second Brahmavihara, karuna, because if we can get a clear idea of what karuna is and isn't, we may catch a glimpse of how we can genuinely extend this quality to all beings in a boundless way. Compassion and its far and near enemies Whereas metta has a whole range of common translations, karuna is pretty much universally translated as compassion, except in some very old translations where the (deeply unhelpful) term 'pity' is used instead. In the rest of this article, I'll use 'compassion' to refer to karuna, and define the term 'pity' slightly differently to distinguish it from compassion. So what actually is compassion? The Latin root of the word is com-, 'with', and -passion, 'pain' (as in 'the Passion of the Christ'). So 'compassion' literally means 'to be with pain'. And that's not a bad definition, but it does need a little nuance. Compassion in the Buddhist sense is the recognition that suffering is a universal human experience, and the earnest desire that that suffering be relieved. (Its opposite, or 'far enemy', is cruelty - the desire to inflict suffering on others actively.) We know from our own experience that life sucks from time to time - maybe often, maybe not so often, but it's a rare (probably non-existent) person instead who can say hand on heart that they never experience pain, unhappiness, irritation, frustration, fear or grief. And - at least in those moments when our heart is open - we feel a natural wish arising that that suffering be reduced or eliminated. The key to the Buddhist practice of compassion is to recognise that all suffering is deeply unpleasant, and it would be better if it were alleviated, no matter whose it is. So far, so straightforward - but we have to be a bit careful, because it's easy to fall into one of a couple of near enemies of compassion. One - as I've already hinted - is 'pity'. When we pity someone, we feel sorry for them, but in a way that puts them over there, somewhat beneath us. Pity is a quality that separates me from you, whereas compassion actually brings us closer together - I see that you suffer in just the same way that I do, and it would be just as good in the grand scheme of things for your suffering to be relieved as it would for mine. So if there's any sense of superiority, contempt or judgement in the attitude we're bringing toward someone else's suffering, we may well have gone astray into pity. Another near enemy is an unhealthy empathy for someone else's pain - we don't simply recognise their pain and experience the desire to relieve it, but we actually start to take on their pain ourselves, to the point that we can become overwhelmed. People who work in caring professions often speak of 'empathetic burnout', where the constant exposure to the suffering of others gradually overloads their own capacity to handle pain. If we're going to make our compassion truly boundless, we simply can't feel the entire world's suffering - it's far too much. We need to find a stable footing in the face of all that misery, so that we can be of service rather than simply being crushed by it. We'll talk more about this 'stable footing' in a couple of weeks, when we get to equanimity, but for now it may help to emphasise the 'desire to help' side of compassion as opposed to the 'recognition of suffering' aspect. If compassion practice simply makes you feel bad, it's gone slightly off course; rather, we should feel a motivation to help in response to the suffering, and focusing on that motivation can help us to stay with compassion rather than sliding over into pure empathy. A final near enemy is very similar to one of metta's near enemies - a deliberately ostentatious kind of 'compassion', where we do good deeds at least in part to be seen as someone who does good deeds, as a badge of social status, or as a way to feel superior to others and maybe shame them for not being as compassionate as ourselves. Needless to say, if this kind of stuff is coming up, the practice has gone badly astray. We can actually end up here if we overemphasise the 'wanting to help' side of compassion at the expense of the recognition of the shared nature of suffering. True compassion causes us to recognise our commonality with all beings, rather than placing us on a pedestal above everyone else, bestowing our generosity from a position of safety. If you find that compassion practice is actually distancing you from others (perhaps as a result of taking my advice in the previous paragraph and focusing more heavily on the urge to help!), shift the emphasis more to the recognition of the universal nature of suffering. At this point it might sound like compassion practice is really difficult, with huge pitfalls on either side and a very narrow path to walk in the middle. In practice, however, it isn't as hard as it sounds (although that doesn't mean it's easy). It can take some time to identify and disentangle pity, empathy and compassion, but keep at it. You can be a fair way off to one side (too much empathy or too much pity) and still find the practice valuable, and over time you'll develop a finer appreciation for exactly what's going on in your practice, and will be able to tread the path with more care and subtlety. Developing an appreciation of emptiness and non-duality can also help, because compassion's near enemies are all related to dualistic perception and the sense of self which drives so much of our behaviour. As we see that we aren't so separate from others as it first appears, compassion becomes much easier and more natural, and the problems of empathy (over-identifying with another's suffering) and pity (under-identifying with another's suffering) tend to fall away. So hang in there! OK - now that we have a clear sense of what compassion is, it's time to return to our earlier question: how are we supposed to make compassion truly 'boundless', without any preference for friend or foe? Breaking down the barriers Traditional Buddhism offers us a step-by-step technique to help us make our compassion (and the other three heart qualities) boundless. We begin with a person (or other being) for whom we can feel the quality quite easily; then we move to ourselves, then to a friend, then to a neutral person, then to a difficult person. Finally, we open up to all beings everywhere. The idea is that we start with the easiest possible situation, to get the emotion up and running clearly, and then move through a sequence of people, progressing from easier to more difficult. (As we discussed in last week's article, however, for many people today sending compassion to themselves is not easy at all - if you're in that category, please check out the Three Flows of Compassion that I describe in that article.) At first, it's very natural to find it much easier to send goodwill or compassion to a dear friend than a bitter enemy. But, if we keep at it, over time something remarkable happens - we start to 'break down the barriers' that close off our hearts to our enemies, and we begin to find compassion flowing more evenly in all directions. That being said, some people can be really difficult at first. Fortunately, traditional Buddhism also has some specific remedies for the most difficult people - so clearly this is not a new problem! Let's take a look at a few of the approaches that the old texts recommend. 1. Try to find something positive in the person. OK, so they annoy the heck out of you... but maybe they're kind to their kids; or perhaps they have a totally excessive attention to detail which irritates you no end, but at least that means they're conscientious in their work. Can you find any redeeming quality at all in the person? 2. If they have no redeeming qualities at all, can we at least have compassion for how difficult life must be for someone with no redeeming qualities at all? This step can really help if you've already spent a fair bit of effort trying and failing to find a redeeming quality - it can even inject a moment of humour into a meditation practice that has potentially become a bit serious and grumpy by this point, helping the heart to relax just a little. But if this doesn't work either, there are some more suggestions... 3. Recall that by continuing to resent the person, you hurt only yourself. It's sometimes said that holding a grudge is like drinking poison and waiting for your enemy to die. This person may not even have any idea that we dislike them this much - yet here we are, raging and stewing in our meditation, filling our minds with negative thoughts about them. By continuing in this way, we harm only ourselves, so maybe we should stop! 4. Deconstruct them. If none of the above has worked, we can try another technique that seems a little weird at first, but can really help. We deconstruct them into parts, to try to identify exactly what we're so annoyed by. Let's say this person makes us angry. Are we angry with their teeth? Their hair? Their eyeballs? Their lymph nodes? And so on. Metaphorically dismantling a person into their constituents in this way can help to diffuse our negative mood quite effectively. 5. If all else fails, reflect on the benefits of compassion practice, and how we're missing out on those benefits by continuing to hold a grudge. But what are the benefits of compassion practice? You'll have to wait until next week's article to find out! Or, better yet, give it a try, and find out for yourself... See you next week, and may you be free from troubles of body and mind in the meantime!

0 Comments

How the three flows of compassion can help your BrahmaviharasOver the next few weeks I'll be putting out a series of shorter articles exploring aspects of the Brahmaviharas. I'm currently writing a four-week course exploring these rich, beautiful practices, and I'll be using these articles (and my Wednesday night class) as a way of beta-testing the material. They'll probably be a little bit shorter than usual because I already have fairly comprehensive Brahmavihara instructions elsewhere on my website, so feel free to check those out if you aren't familiar with these practices and want a concise introduction.

What are the Brahmaviharas anyway? The Brahmaviharas are a set of four heart-opening practices. The name of these practices comes from a discourse in early Buddhism, Majjhima Nikaya 99, in which Subha, a practitioner of Brahminism, comes to the Buddha. Subha has heard that the Buddha teaches 'a path to companionship with Brahma', and wants to know what it is. Buddha replies with the following: Firstly, a mendicant meditates spreading a heart full of love to one direction, and to the second, and to the third, and to the fourth. In the same way above, below, across, everywhere, all around, they spread a heart full of love to the whole world—abundant, expansive, limitless, free of enmity and ill will. [...] This is a path to companionship with Brahma. The same formula then repeats for 'a heart full of compassion', 'a heart full of rejoicing' and 'a heart full of equanimity', giving us four heart-opening practices in all. This week we'll focus on the first one. The first Brahmavihara: loving kindness, goodwill or well-wishing The first Brahmavihara is best known either by its Pali name, metta, or by its standard English translation, loving kindness. However, a wide variety of other translations exist - benevolence, friendliness, well-wishing, and so on. Personally, I like 'goodwill' (which I'm borrowing from Soto Zen teacher Domyo Burk, whose 'Zen Studies Podcast' I highly recommend), for reasons I'll explain momentarily. You'll sometimes also see the Sanskrit spelling, maitri, especially in Tibetan circles. (This is the same word that forms part of the name of the Buddha of the future, Maitreya, 'the kindly one'.) However you want to translate it, the general idea is that it's the quality of wishing someone well - not because they aren't currently doing well, but just because it's good when things are going well. Genuine metta is sometimes compared to its near enemies - qualities which are superficially similar, or have something in common, but miss the point in important ways. Traditionally, lust and greed are said to be near enemies of metta, because all involve a kind of attraction (a 'movement towards'), but metta is open-hearted and no-strings-attached whereas lust and greed have personal gain in mind. There's also another kind of 'near enemy' of metta that people in the spiritual world are often prone to - a kind of showy, ostentatious 'kindness' which is really just another ego support. Genuine metta practice actually does make you feel good, but not by lording your infinite kindness over the people around you! Metta can also be contrasted against its far enemy - ill will, or wishing harm to others. (Contrasting metta with ill will is why I like 'goodwill' so much as a translation!) Ill will is 100% in the opposite direction to metta, so much so that metta is often given in the early discourses as an antidote to ill will. The three flows of compassion So far so good - but not everyone has the textbook experience of boundless love and goodwill when they sit down to do metta practice. In fact, for many people, this practice can leave them totally cold, or even bring up unpleasant feelings. What's going on here, and is there anything we can do about it? A very helpful concept that's been doing the rounds for the last few years is the idea of the 'three flows of compassion' (although they aren't limited just to compassion - they work equally well for all four Brahmaviharas). These are three directions that emotions can travel:

It's very common in Western society to find people with extraordinary levels of self-hatred, or who have had extremely damaging experiences that make them mistrustful of others. Consequently, we can find ourselves 'blocked' in one or more of these directions.

Traditionally, metta practice starts by wishing ourselves well (self to self), then moves on to wishing others well (self to other). But if we're blocked in the self-to-self direction, it can feel like we're pushing against a brick wall even to get started. Or if we're blocked in the self-to-other direction, we might start out okay but then come to a screeching halt when it comes to extending goodwill to others. To make matters worse, there's usually at least one person in each group who falls in love with metta right from the first practice session and can't stop talking about how great it is - which only makes us feel worse if we're experiencing blockages in our own practice. What kind of stone-hearted monster are we, anyway? If our blockages are really severe, perhaps because they're rooted in trauma, then actually it might be more helpful to speak to a therapist rather than continuing to bang our heads against a brick wall. Silent meditation is a great practice but it isn't a universal panacea, and if our inner landscape is a difficult place to be then closing our eyes and turning inward for long periods of time might actually not be the most skilful thing we can do until we've done some other work first. That said, it can be worthwhile playing around with the three flows of compassion, to see if we can find any direction in which we can connect with the feeling of the Brahmavihara in question. Once we have it up and running, we may be able to turn very gently in another direction, and gradually chip away at our blocks over time. So if you find it difficult to start with yourself, you could either put yourself last, or you could swap out the 'self-to-self' step for an 'other-to-self' step: imagine someone else sending goodwill to you, and see how it feels to receive it. You can experiment with feeling the goodwill coming from a friend, a mentor, a parent or anyone who has helped you in the past. If nobody comes to mind, or the relationships that do come up are too fraught, complex and problematic, you can alternatively imagine an ideal caregiver - the kind of person you would love to have in your corner, who always has the time, patience, care and interest to give you, whenever you need it. As with any meditation practice, go gently, and remember that you can come out of the practice at any time - you're in control of what's happening. If difficult memories or emotions start to surface, and it's all getting too hot to handle, you can open your eyes, look around, feel your feet on the floor, and deliberately notice that you're safe right now, no longer in the difficult situation that the practice has brought up. Designing your own metta practice If you're one of the fortunate people for whom traditional metta practice works straight off the bat, then enjoy it! It's a great practice, with many benefits that we'll explore in coming weeks. But if it doesn't feel like such a good fit on your first try, don't worry about it. It doesn't mean that there's anything wrong with you - it just means that the practice might need to be tweaked before it's a good fit, perhaps by exploring the three flows of compassion to find the direction(s) that are easiest for you, or even set aside for a while so that you can pursue other practices that do resonate better with you. Personally, it took me quite a while to get into metta practice, and from time to time I would wonder if I was some kind of monster with a cold, dead heart of stone! These days, metta is a go-to technique for me, and I'm immensely grateful to the teachers who have shared it with me. I hope you benefit from it too. Walking the Elephant Path to tranquillityA key meditative skill is samadhi - the practice of focusing the mind on an object, calming the usual mind-wandering process and bringing greater clarity to one's experience. Different traditions have come up with different approaches to achieve the same end; the early Buddhist tradition used jhana practice as its primary vehicle (the Pali canon defines 'right samadhi' as practising the jhanas), but later traditions evolved other approaches that were less reliant on altered states of consciousness, placing greater emphasis simply on working with the raw material of attention itself.

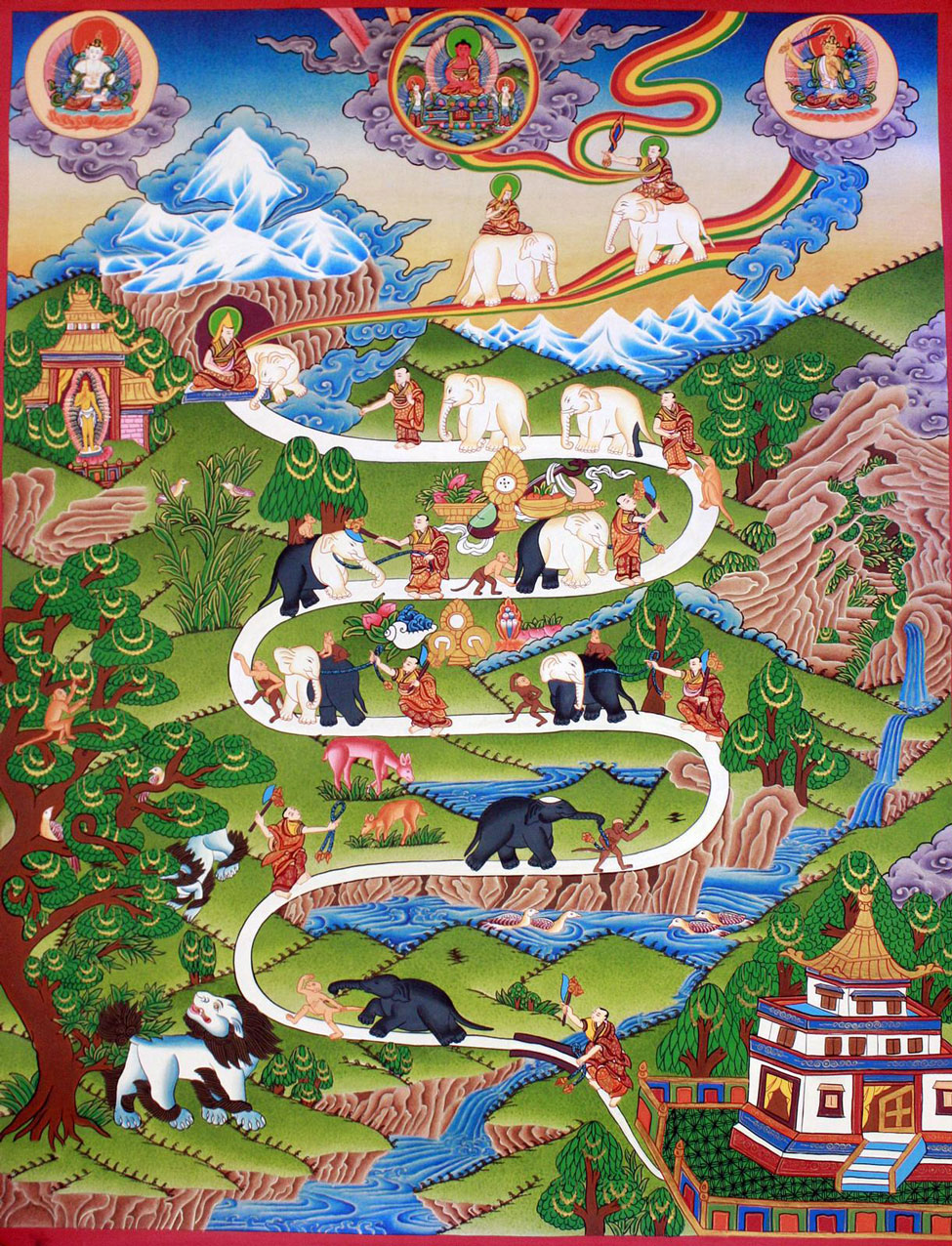

In this article we'll look at what's sometimes called the 'Elephant Path', a description of the stages of cultivation of samadhi commonly found these days in Tibetan Buddhism, but also sometimes used in other systems - notably in The Mind Illuminated by the late John Yates, a manual of samadhi practice which is largely framed in Theravada terms despite its use of a Mahayana/Vajrayana map. Long-time readers of these articles may notice some similarities to the stages of samadhi described by Chan master Sheng-Yen which I've previously written about. This is no accident - while the specific language and techniques vary from tradition to tradition, the actual process of stabilising the mind is universal, and travels through very similar territory from person to person. The only difference between these maps is the specific landmarks along the way that each map has chosen to highlight. Basics of samadhi, and the cast of characters In a sense, samadhi practice is very simple. Place your attention on an object of focus - anything will do:

Then, whenever you notice that your mind has wandered away from your object, simply let go of the distraction, take a moment to relax, and then return to the object. That's it! Sounds simple, right? But give it a try, and you'll find that the actual experience is not so straightforward. In the picture, the mind is represented by an elephant. It's huge and powerful, and can be a valuable ally when it cooperates, or alternatively it can rampage around causing destruction. And so the purpose of samadhi training is to teach the mind to cooperate with us through the use of focused attention, represented in the picture by the monk. The first obstacle to samadhi that we encounter in practice is distraction, represented in the picture by a monkey. The mind loves to wander! Some days it can seem that no sooner have you placed your attention on the object than it's already wandered away. Just as a monkey moves through the trees by grabbing first one branch and then another, the mind loves to grab on to whatever comes its way. The second obstacle that we run into is dullness, represented in the picture by a rabbit (perhaps because they sleep a lot during the day?). Dullness is when the mind begins to switch off, either subtly or dramatically. Although the rabbit doesn't show up until the third stage of the picture, many beginning meditators find dullness can creep in almost immediately, their eyelids becoming heavy within moments of starting the practice. I suspect this is at least partly due to the busyness of modern life - our bodies are trained to understand that the only time we stop moving and close our eyes, it's time to sleep, and we're so chronically sleep-deprived that any excuse will do. There are other obstacles that can come up (e.g. the Five Hindrances), but basically we can categorise all of them as leading to distraction or dullness, for the sake of convenience. So the process of cultivating samadhi relies on finding our way between the twin pitfalls of distraction and dullness, gradually training our minds to focus more and more consistently on our object. Two basic strategies can help us to navigate the winding path between distraction and dullness, which we might call 'intensifying' and 'easing up'. Intensifying here means strengthening your intention to focus on the object; easing up means relaxing. Intensifying can be a helpful strategy for dealing with dullness - literally waking yourself up by bringing a little more energy into your practice - while easing up can be a helpful antidote to distraction. The latter point is especially important, because often our instinctive reaction to mind-wandering is to knuckle down and 'try harder'. Unfortunately, though, this is often counterproductive, resulting in a mind which is increasingly tense and ***constricted. The knack is to maintain a sense of relaxation without dropping the intention to focus entirely. Generally speaking, the sweet spot in samadhi practice is just enough intensity of focus to stay with the object, without slipping down into dullness and without becoming tense. The only problems are that it takes quite a while to develop enough sensitivity to your own mind state to get a feel for whether you're too tight or too loose, and that the sweet spot moves around as we progress along the path toward greater focus. So we're aiming for a moving target in the dark - no wonder it's not as easy as it sounds! Nonetheless, the skill does come with time - it's just a matter of practice. Having now set the stage, let's take a look at the Elephant Path in detail. (The names I'm giving to each stage come from the Dalai Lama's book How To See Yourself As You Really Are, which I highly recommend.) Stage 1: Putting the mind on the object We start at the bottom of the path, leaving home and attempting to climb the winding path to enlightenment. But it quickly becomes clear that the elephant has no interest in listening to our suggestions - it runs off ahead, following the monkey, going this way and that, as we chase along helplessly behind it. This stage represents a very common experience which beginning meditators unfortunately tend to interpret as proof that they 'can't meditate'. The mind resists any attempt to impose order or focus; all the practitioner sees, in their brief moments of lucidity, is a fast-flowing river of thoughts and emotions which is too powerful to resist. How can this possibly be brought under control? Actually, as unpleasant as this experience can be, it's the first sign of progress. Many people have no idea how chaotic their minds are, whereas at least the beginning meditator has taken a close enough look to see the current state of affairs. That very perception of the torrential flow of thoughts and feelings is the first insight of the practice. Stage 2: Periodic placement If we keep practising, we begin to make some headway. The mind is still largely out of control, but we have moments where we can stay with a few breaths in a row, or a few repetitions of our mantra. In the picture, the elephant and the monkey are still way out in front, but they've slowed to a walking pace, and the tops of their heads have changed colour, to symbolise the gradual purification of the mind through practice. At this point we're still mostly distracted rather than focused, but those brief moments of stability offer us an important glimpse that the practice is starting to bear fruit. It's helpful if we can notice and celebrate those moments as a positive sign of progress, as opposed to using them as an opportunity to beat ourselves up for being 'bad meditators' - which, unfortunately, is a common reaction, even among experienced meditators. But if we slap ourselves on the wrist every time we have a moment of focus, we're actually subtly discouraging ourselves from learning to concentrate - because who wants to get slapped on the wrist? If, instead, we make those moments a positive and rewarding experience, we're more likely to gravitate there in the future. Stage 3: Withdrawal and resetting As time goes on, we become more sensitive to the process of getting distracted, and we notice sooner when the mind has wandered. We start to experience more continuity with the object, and we don't wander quite as far away when we do lose it, although we may still lose it quite frequently. In the picture, we've finally got the elephant's attention - previously, the elephant was being led around by the monkey, but now the monk has taken hold of the rope. However, notice that the rabbit has now made an appearance. As the mind settles and becomes more stable, we become more prone to sinking into dullness. The mind isn't wandering so much, and so there's less excitation in the system generally. If we don't balance that with a certain degree of energy from our own side, we tend to sink toward mental blankness, a kind of 'zoning out' that can feel vaguely pleasant but which is actually drawing us away from the cultivation of samadhi. The Buddha described a concentrated mind as 'clear, sharp and bright' - the opposite of dullness. So watch out for that sneaky rabbit! Stage 4: Staying close As we progress beyond stage 3, and the major distractions and dullness of the earlier stages are gradually more under control, we can start to feel like we've cracked it. But now is the time to 'stay close' - to keep a closer and closer eye on the wavering of our attention, represented in the picture as the monk closing in on the elephant, monkey and rabbit, to see them more clearly. At this point, we might no longer find ourselves waking up from a ten-minute mental digression, but we might notice that we're quite capable of continuing to focus on the breath whilst holding a conversation with ourselves at the same time. This is a subtler kind of distraction - we don't fully lose the object, but we aren't fully focused on it either. So the focus at this stage is staying closer and closer to our object, without drifting into subtle distraction. Stage 5: Disciplining the mind As we get to grips with subtle distraction, its counterpart, subtle dullness, comes to the fore. (Notice that in this picture the monkey isn't even shown - it's all about the rabbit here.) In the same way that in the previous stage we felt we've conquered distractions, only to notice a subtler form coming to light, we may feel that we're no longer flat-out falling asleep in practice, but even so a subtle dullness can still creep in. If you notice sudden noises triggering a much greater-than-usual startle response, that's a good indication of subtle dullness. Again, intensifying is the antidote, but because the dullness is subtler, the intensifying will have to be subtler too. Our practice is becoming much more refined at this point - by comparison, our previous techniques start to look a bit ham-fisted, even though they were exactly the right thing to be doing at the time. In the picture, this stage is represented by the monk touching the elephant's head with his staff, as a symbol of the subtle but continuous holding of intention required to overcome subtle dullness at this point. Note, too, that the monk is now out in front of the elephant, rather than trailing behind as in the previous stages. Stage 6: Pacifying the mind In the picture, the monk is now out in front, looking ahead and enjoying the scenery rather than focusing on the elephant, who is now sufficiently on-side to follow the monk obediently. But the monkey isn't quite done yet - he's still there, quietly tugging on the elephant's tail, hoping to persuade his old friend to come for another adventure. We're now at a delicate point in the practice. The mind has become stable, and we've overcome subtle laxity - but the balance between intensifying and loosening up is becoming increasingly delicate, and we can easily put too much energy into the system and wobble off into subtle distraction again. The key now is to take the foot off the pedal and relax, allowing the system to find its equilibrium. Stage 7: Thoroughly pacifying the mind At this stage, the mind is almost - but not quite! - fully pacified, represented in the picture by the elephant having almost entirely changed colour, apart from part of one leg. Also, the monk is standing between the monkey and the elephant, preventing the monkey from distracting the elephant's progress. We're nearing the end of the road now. Our skills of introspection, gently intensifying to counteract the very beginnings of dullness and gently loosening up to counteract the very beginnings of over-excitation are now fully developed, and almost nothing has to be done to keep the mind focused on its object. Soon we won't need even this much deliberate focus - but if we try to jump too soon to completely effortless practice, we might find that we fall back a stage or two, so this is a tricky point in the process. Stage 8: Making the mind one-pointed The monkey is gone, the elephant fully purified. It's enough for the monk to indicate the way; the elephant will obediently follow the path without further instruction. In the same way, at this stage we simply set the intention to focus on our object at the beginning of practice, and the rest of the practice unfolds effortlessly. Stage 9: The mind placed in equipoise The culmination of the path of stabilising the mind, now the monk is shown in a state of calm abiding, the elephant curled up at his side. At this point, the state of effortless focus establishes itself at the slightest intention, and remains in place without any need for interference. The mind is simply at rest. The path beyond, and the insights that await The picture then shows two more stages along a rainbow road. These symbolise the path to enlightenment through insight. Samadhi and insight practices have always appeared together in Buddhism, and for good reason - while insight is certainly possible without a deep samadhi practice, it tends to come more easily and touch us more deeply when the mind is focused. So why not give it a try? If you have a samadhi practice already, does this map resonate with you? If so, perhaps the suggested points of practice along the way will help you to take it a little further. And if you've never tried this type of practice before, you can set off on your journey secure in the knowledge that you have a roadmap, and that the inevitable obstacles you'll encounter at the start of the journey are categorically not a sign that you're 'failing' or 'a bad meditator', but simply part of the path that we all go through. Safe travels! Zen's approach to thoughtI once saw an advert for a local Zen group which said: 'Zen: it's not what you think.' I liked that, because I like wordplay, although to be fair I didn't like it enough to go to the Zen group, so make of that what you will.

Regardless, Zen has an interesting relationship to thoughts, knowledge and learning. Sometimes Zen is presented as being totally anti-intellectual, anti-thought, anti-philosophy, anti-learning, but that isn't entirely accurate. While the central core of Zen is experiential rather than intellectual, nevertheless Zen has produced a vast body of literature, and experienced students will typically be required to study classic texts and demonstrate their knowledge and understanding. Ultimately, Zen practice must be integrated with every aspect of life, and that includes our relationship to thought. Thoughts are not the enemy When I meet people who are interested in taking up meditation and I ask them what they're hoping to get out of it, the most common answer by far is something like 'I want to be able to clear my mind.' Despite my best efforts to manage their expectations, they're usually disappointed to find that their minds don't fall silent the moment they sit down to practise, and if anything they start to notice their thoughts even more as they begin to develop some introspective awareness. However, this is one of those good news/bad news situations. On one hand, it's very unlikely that beginning practitioners will be able to 'stop their thoughts' - most folks will need a pretty heavy-duty level of samadhi to come even close to a silent mind, and that takes a lot of practice. On the other hand, though, people who persist with the practice long enough usually find that they don't actually need to stop their thoughts. It becomes clear after a while that it isn't the thoughts themselves that are the problem so much as our relationship to them. Thoughts are like sounds - they come and go. We hear sounds because we have ears; likewise, we think thoughts because we have a brain. It's what happens next that's the key bit. We tend to give our thoughts a lot of weight. When a compelling thought arises ('oh no, I forgot to do something at work yesterday!'), our attention will often naturally shift to that thought, and more similar thoughts will start to come up ('that means so-and-so won't be able to do what they need', 'they're going to be angry with me', 'I'm so careless, why do I do these things?'). To make matters worse, we tend to assume that our thoughts are true - after all, it's me thinking it, and I'm pretty switched-on, so it's gotta be right, hasn't it? The trouble is that thoughts are just thoughts, just ideas that have bubbled up into our heads, and they may or may not have any connection with reality at all - so the more easily and unquestioningly we believe them, the more we're prone to self-deception and confusion. So meditation practice very often involves turning the focus deliberately away from the thoughts, or cultivating specific thoughts rather than letting the mind roam freely. In mindfulness of breathing, for example, we place our attention on the physical sensations of the breath, and when thoughts come up we simply let them go and come back to the breath. After a while our mind starts to get the message that, at least while we're doing this meditation, the breath is interesting to us and thoughts are not interesting, and so the thoughts fade into the background and stop distracting us so much. In metta practice, we might use specific phrases ('may I be happy') to focus the mind on a particular thought which evokes goodwill, and again after a while the mind gets the idea that, just for now, we're staying on this one thought of wellbeing rather than wandering around freely as usual. 'Don't know mind' Zen is often associated with something called 'don't know mind'. As I mentioned earlier, it can be easy to interpret this as some kind of 'philosophy of ignorance', especially if you've heard Bodhidharma's classic description of Zen as 'a special transmission outside the scriptures, not depending on words and letters'. (If you've ever tried to read one of the more difficult Zen texts, such as the Lankavatara Sutra, it can be very tempting to say 'Oh, well, Zen is outside words and letters' and quietly put the heavy, impenetrable book down in favour of the latest Expanse novel... Or maybe that's just me.) Rather than a suggestion to avoid learning, however, 'don't know mind' is actually a teaching which encourages us to explore our thinking mind and see its limitations. Again, our thinking mind is not a bad thing - it's super-useful to be able to solve the problems that come up in the course of our work and our lives. The only danger lies in letting it completely run the show. I've written several times about insight - here, here and here, for example. One of the most powerful and transformative uses for meditation is to develop insight - to see deeply into our true nature, to see things as they are, to discover for ourselves what's really going on as opposed to what we think is going on. And that's the key right there - we think that our minds and our lives work a certain way, but our thoughts are not quite in sync with our experience - sometimes not at all! Nevertheless, we tend to see the world through the reference frame of our concepts - our ideas about the world. We filter what we experience through what we expect to have experienced - and if something doesn't fit, we explain it away, brush it under the carpet, or get angry with the universe for subverting our expectations. Insight comes about when we can break out of that reference frame and see something new about what's going on - when we realise the limitation of our old way of seeing, and adapt accordingly. The more this happens, the more it becomes clear that we should hold our concepts and reference frames lightly. The tighter we cling to them, the more upsetting and destabilising it is when we discover their limitations - or the harder we have to work to keep pretending that those limitations aren't there. If we can instead acknowledge that we really don't know how things work, at least not completely, then we can be more flexible and responsive in situations that challenge the way we see the world. What can we know, anyway? Through this practice, we also begin to discover how complex the world truly is. At any given moment, we only see one tiny part of what's going on, and it can be extremely difficult, if not impossible, to predict how even the simplest of decisions will turn out. Suppose a valuable member of my team at work is becoming dissatisfied and thinking about leaving. I value that person, and so I want them to stay - so I should try to encourage them to stay, right? Then again, leaving might be absolutely the right decision for them - and for all I know, the person I recruit to replace them might be even better. Or perhaps the person I recruit is actually worse, and causes lots of problems in the team - but in the process, the actions we take to fix the damage they're going actually makes things better in the end than they had been before. Or... You get the picture. I've mentioned Prof John Vervaeke's excellent YouTube series Awakening from the Meaning Crisis before. In one of his videos, Vervaeke asks the question 'Do you want to be a vampire?', and points out that we can't answer that with any degree of certainty. We might have ideas about what it would be like to be a vampire, but those ideas are rooted in who we are now. Becoming a vampire would change our lives so radically that, by the end of the transformation, we would have little in common with who we are now, and that person might feel totally differently about whether they want to be a vampire or not. Even if the idea repulses you right now, the future vampire you might think it's totally cool - or vice versa. The more we explore these kinds of questions, the more we see how very contextual our experience is. We tend to think of ourselves as fairly solid entities with fixed personalities, travelling through a fairly solid world made up of fairly solid things that are the way they are. But the more we look, the more we find not things but relationships. If I lose interest in what used to be my favourite TV show, that might be because the quality of writing or acting has declined (i.e. the TV show changed), or it might be because my personal tastes have drifted (i.e. I changed), or that something in the wider world has happened which has changed the context (e.g. maybe my favourite TV show was about a global pandemic which is somehow less appealing than it used to be in light of Covid-19). The more we look, the more we see connections and relationships in all directions - and those relationships depend on further relationships, which depend on further relationships and so on. Sooner or later we find that it takes the whole universe to be as it is for even a single thing to happen. The world, and our relationship to it, becomes more mysterious as we realise the limitations of our knowledge - but, far from being threatening or confusing, it's actually beautiful, even miraculous. (We might even start to notice how very certain the people around us are about everything, and how often that certainty is misplaced.) Applying this to our practice So how can we work with all of this in meditation? One approach is simply to practise treating thoughts like sounds, or any other distraction. Whether you're sitting in Silent Illumination, focusing mindfully on the breath or doing jhana practice, simply let the thoughts come and go in the background, like someone's left a radio switched on in your mind but the radio programme is completely irrelevant to your interests right now. Even in a practice like the Brahmaviharas or working with a koan, where you're deliberately introducing a thought from time to time, remember that the thoughts are not the ultimate point of the practice - they're just a means to an end, and so we can and should let them go, in order to make more room for the practice to unfold. Another approach is to explore this directly. You could perhaps work with a question such as 'What do I know for certain?' as a koan, or examine a recent decision in your life and look at all of the hidden dependencies, all the things you didn't know then that you've since discovered, all the things you may never know. See for yourself the limitations of our knowledge - and maybe catch a glimpse of life's mystery for yourself. Finding the stillness within all thingsThe great Rinzai Zen master Bankei Yotaku (1622-1693) gave a series of talks to lay practitioners near the end of his life in which he described the entire practice of Zen as 'resting in the Unborn'. It sounds simple - but what does it mean, and how do we do it? Let's find out!

The Unborn Buddha-mind Bankei's phrase 'the Unborn' refers to a discourse from early Buddhism, in which the Buddha declares the following: There is, mendicants, an unborn, unproduced, unmade, and unconditioned. If there were no unborn, unproduced, unmade, and unconditioned, then you would find no escape here from the born, produced, made, and conditioned. But since there is an unborn, unproduced, unmade, and unconditioned, an escape is found from the born, produced, made, and conditioned. Clear as mud? Anyway, when Bankei had his great moment of awakening, it was this passage which resonated with him, and he later described his realisation as 'Everything is perfectly resolved in the Unborn.' (Bankei felt that 'unborn, unproduced, unmade and unconditioned' was a bit of a mouthful, so he shortened it to 'unborn'.) So the approach to practice that he recommended was first to discover the Unborn for yourself, and then learn first to rest and eventually to live entirely from that place. (And if that sounds like the approach I described in last week's article of discovering, connecting with and living from your Buddha Nature - yep, that's it!) As an aside, at other times Bankei referred to the Unborn by another name, the Buddha-mind. I tend to use the term Buddha-mind myself because the word 'unborn' can sometimes have unhelpful associations for people who have had difficult pregnancies or similar experiences. For the purposes of today's article, however, I'd like to stay with the term 'unborn' because exploring it will lead us into a fruitful meditative inquiry into the nature of our experience. If the term does have unwanted associations for you, please accept my apologies. We name the wars but not the peace in between I think I was still a teenager (a long time ago now!) when I first heard someone observe that historians tend to give names to periods of war (the First World War, the Hundred Years War, the Gulf War) but not the periods of peace in between - as if the wars are when 'something happens', and are thus worthy of a name, whereas the peace is a period when 'nothing happens', so there's no need to name it. This tendency to notice and focus on the 'things' and ignore the 'nothing' is pretty deeply wired into us. If you take a moment to look around you, you'll probably notice the things around you - computer, phone, chair, table, tree - rather than the space between the things. Why bother to notice the space? It's just space, after all - it's empty, there's nothing there. In the same way, when we meditate, we tend to be naturally drawn to the 'things' in our experience; indeed, most meditation techniques actively involve placing the mind on a particular 'something' - the bodily sensations, the sounds, the sights, a visualisation. And when we get distracted, we're invariably distracted by another 'something' - who ever heard of getting distracted by nothing? As we spend time with the 'things' in our experience, we gradually realise that they aren't 'things' at all - they're actually 'events'. Everything we see, hear, feel and think has a beginning, a middle and an end. Some events are very short-lived and some hang around for longer, but they're all fundamentally impermanent - they all come and go sooner or later. This is a classic insight that can come out of 'event-focused' meditation practices such as paying close attention to the sensations of the breath. As you've probably already guessed from the way I'm setting this up, though, focusing on the 'events' in our experience isn't the only way to practise insight meditation. Another approach is to 'turn the light around' and focus on the awareness itself - on that which is aware of the events. How do you persuade a knife to cut itself? It's relatively obvious how to pay attention to the sensations of the breath. But how is one supposed to be aware of the awareness itself? The very thing you're looking for is the thing doing the looking! As strange as it may sound, this seemingly paradoxical - perhaps even impossible - inquiry can provide a turning point for many practitioners. So if you fancy a challenge, stop reading now and give it a go. And to be sure, it's a bit mind-bending at first (no pun intended). But there are a few approaches which can help us to get in touch with our awareness. One approach is to come at it indirectly - to start by working with the events of the mind, but then turn your attention to trying to discover what all of these events have in common with one another - their 'true nature', if you will, the thread that binds them all together. This binding thread turns out to be awareness itself - by definition, whatever event you're looking at, that event is arising within awareness. We never experience anything outside of awareness; whatever events we examine, we are examining the functioning of our awareness. Another way to say this is that awareness is the nature of the events we experience. Another approach is to direct our attention away from the events of our experience in a deliberate way, the idea being that if we continue to be aware but we aren't drawn into any particular event, there's nowhere left to go but the awareness itself. For example, we can pay attention to the space between objects, the silence between sounds or the gap between thoughts. (After a while, we start to get a sense that the spaciousness, silence and stillness is actually everywhere - for example, that the silence is not just 'between' but also 'behind' and 'around' sounds, and perhaps even 'within' sounds in a certain way. This is another sign that we're connecting with awareness.) A third approach is to search for something that you can't find, such as the self (as we discussed last week) or even the awareness itself. You can't find 'self' or 'awareness' no matter how carefully you search the events of your experience, because they aren't themselves events - and in the repeated failure to find them and the ensuing frustration, the mind becomes disillusioned with the failing strategy of focusing on the events all the time, and opens up to the possibility of connecting with experience in a different way. Connecting with awareness and discovering the Unborn So what happens when we connect with awareness itself? It's sometimes described as a kind of foreground-background shift - everything kind of turns on its head. Rather than seeing things in terms of separation and comparison, we see things holistically, all part of one seamless whole. We experience a kind of unity, a sense that everything is deeply interconnected and not truly separable. We sense that the 'things' of our experience are not really 'things' at all, but only appear that way to us because our minds are putting boxes around parts of our experience and labelling them for our convenience - essentially, that the 'world of things' that we experience is only a projection of the mind as opposed to being an ultimately true account of how the world is. On closer inspection, our experience becomes more mysterious still. Previously, we may have thought of our 'awareness' as something arising from our brain and body, but experientially it's actually the other way around - awareness comes first, and within that awareness arises all the events that we then identify as brain and body. Even time itself can flip around if we look deeply enough. What actually is time, anyway? We experience the passage of time by tracking events - the sound of a ticking clock coming and going, or the rhythm of the breath rising and falling. Again, if we search for 'time', we can't actually find it - we can only find more events, which imply time to us, but time itself is nowhere to be found. Our sense of time is simply another event arising within awareness. Awareness itself is 'outside' of time. This is what the Buddha means by 'unborn, unproduced, unmade and unconditioned', and thus what Bankei is pointing to as well. The awareness - the Unborn Buddha-mind - is not a thing, not an event, not something which comes and goes in our experience. Awareness is the foundation of experience itself, its true nature. Everything else - time, space, thinking, brain and body - arises within awareness. But we're hard-wired to experience things in terms of events, and so even when we begin to connect with awareness, at first we tend to see it terms of the 'nothing' between 'somethings'. People often report having encountered a 'still point' in their experience, or a deep 'inner silence'. The awareness is often compared to space - vast, boundless, empty. And we can start to tap into a profound sense of peace in practice when we connect with awareness in this way, a substantial relief from the crazy bustle of events in our experience. Living in the Unborn Simply chilling out isn't the end of the road, though. The stillness and silence of awareness is only half the story, and if we stop here, we're missing the best part! Zen practice has never been about cutting ourselves off from our lives and simply sitting immobile in peace or bliss waiting to die. Awareness has two aspects. One is its nature, or essence - this spacious, silent, unchanging emptiness that we've been talking about. But it also has a dynamic aspect - usually called its function. The function of awareness is precisely to produce the events of our experience that we had to turn away from in order to see its nature clearly. The awareness is not separate from the events - the events are the awareness, or at least one aspect of it. Awareness is sometimes compared to an ocean for this reason. When we look at an ocean, we see the waves - the 'events' of the ocean, if you like. Waves come and go, change and vanish. Each wave is, in a certain sense, different to every other wave, unique and individual in its own right. Equally, the whole ocean has the nature of water - every wave is simply a different shape of water, and can never be anything else. The watery nature of the ocean never changes, no matter whether the waves are calm or stormy. And, in just the same way that we can enjoy the display of waves whilst at the same time remembering that it's all water, we can learn to experience the spontaneous display of our awareness's functioning whilst remembering that its true nature is stillness, spaciousness and silence. No matter what happens, that true nature never goes away - it simply can't, because it's the Unborn, beyond time and space. As we begin to recognise the true nature of our experience, we gradually find ourselves coming to rest on this bedrock of peace and stability, even in the midst of activity. We can engage more fully than ever in the world, knowing that in a certain sense we're always safe and secure - we've come home to rest in the Unborn. |

SEARCHAuthorMatt teaches early Buddhist and Zen meditation practices for the benefit of all. May you be happy! Archives

June 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed