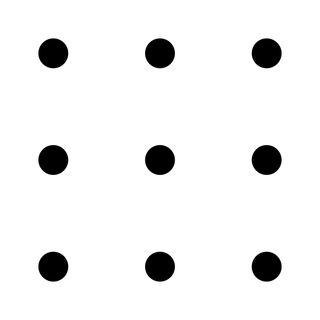

Getting a better grip on what's going onA couple of years ago, someone in my meditation class with a deep personal practice commented how strange it was that 'sitting and doing nothing' could be so transformative. And we laughed... but his comment stuck in my mind, and I've spent a lot of time reflecting on it ever since. What actually are we doing here? We talk about insight and seeing the true nature of reality - but how is that even possible, and even if it is, why does meditation help us to do it? Meditation practice clearly does something, after all. You can find any number of books in which people describe the profound spiritual experiences that changed their lives forever. Often these experiences involve unusual, altered states of consciousness, in which things appear 'more real' than before, and there's a sense of 'waking up' to a 'deeper truth' that was previously hidden from us. But why should altered states of consciousness be given any credence at all, let alone be regarded as life-changing? We enter an altered state of consciousness every night when we go to sleep, but we don't typically regard our dreams as revealing a 'real truth' to us - if anything, dreams are easy to dismiss as a kind of 'mental garbage'. (I've kept a dream diary for a while, and most of my dreams are pretty lame remixes of whatever's been happening to me lately. Not terribly exciting, and not particularly insightful!) But why do we dismiss dreams, yet accept spiritual experiences? Both are private experiences - you have them, but the people around you don't notice anything different to usual. And both are completely out of line with 'consensus reality' - the generally agreed-upon version of 'how things are'. In a nutshell, what makes meditation and spiritual experiences different from dreams is that they're insight-producing. Dreams might be interesting but are not terribly useful. Insight, however, changes the way we see ourselves, our lives and the world around us for the better - it helps us to get a better grip on what's going on. What the heck is insight? Take a look at this picture. Can you find a way to connect all nine dots using exactly four straight lines? (If you give up, the solution is here.)

Whether or not you've seen this problem before, the first time you encountered it you probably had a hard time with it. You try all the obvious things, but they all seem to need at least five lines. It's not until you're able to make the mental leap to 'think outside the box' (this problem is the origin of that expression) that you can solve it. What's going on here? When we first look at the nine dots, our minds tend to see a square, and thus draw a kind of implicit boundary around the nine dots. That boundary delimits the 'playing area' for the problem, and so we try to find a way to work inside that space to connect all the dots. But that boundary is something that we put there, not something that was imposed by the problem. In essence, we unconsciously self-limit in such a way that the problem becomes insoluble. Even being told 'think outside the box!' is unlikely to help us, because we're doing this unconsciously - we don't realise we're self-limiting, so it's very hard to move beyond that limitation until we finally see it for ourselves. Transparency and opacity We say something is 'transparent' if we can see through it. In the case of the nine-dot problem, our limiting belief that we have to work 'insight the box' starts out as a 'transparent' constraint. It's there, but we don't see it - we look straight through it to focus on the problem. It's only when we're able to notice the constraint - when the constraint becomes opaque - that we understand how we've been limiting ourselves, and can move beyond it. We can explore transparency and opacity in another way too, in a way that's going to be relevant for meditation practice. To do this exercise, you'll need two objects - a cup and a pen. You'll be doing the exercise with eyes closed, so read the instructions first! 1. Close your eyes, and begin to tap the cup with the pen. You're trying to explore the cup in a tactile way, using the pen - just by tapping it, you're trying to get a sense of what shape the cup is. Really put your full attention into the cup. (Notice how effortlessly you can do that - how quickly the pen becomes a part of you, and your whole focus goes into the cup.) Spend maybe 15-20 seconds doing this. 2. Then, continuing to tap, shift your attention into the pen. Feel the pen moving as you continue to tap - put your full attention into the pen, now ignoring the cup as completely as you can. Spend another 15-20 seconds here. 3. Then, still continuing to tap, shift your attention into your hand. Feel the sensations in the hand and fingers as they move, holding the pen, tapping the cup. Put your attention as fully into your hand as you can. Spend another 15-20 seconds here. 4. Now we'll go the other way - continuing to tap, shift your attention back into the pen. Again, spend 15-20 seconds here. 5. Finally, shift your attention back into the cup again, and spend another 15-20 seconds here. This simple exercise illustrates how we can shift our reference frame very quickly and easily, almost effortlessly changing what is transparent and what is opaque in each moment. We started out with the cup opaque, and the pen and fingers transparent; then we made the pen opaque (and largely forgot about the cup); then we made the fingers opaque (and largely forgot about the pen); and then we went back the other way again. What does all this have to do with meditation and insight? We see the world through a particular conceptual frame, based around the idea of duality. I see myself as a separate individual, living my own life, with the rest of the world 'out there' and generally not terribly in line with how I want it to be. And we've seen the world this way for so long that it's become completely transparent to us - it's simply obvious, natural, just how the world is. Except it isn't. It turns out that this is a form of self-limiting constraint that our minds are imposing on our experience in order to help us navigate it, based on an over-emphasis of the mind's powerful ability to divide and compare. And what meditation is intended to do is to help us make this self-limiting constraint opaque, and then move beyond it and its many drawbacks (suffering, isolation, alienation, feelings of inadequacy and insufficiency... the list goes on). We can take a couple of different approaches to try to bring about this shift. Our starting perspective is the conventional one - I'm an entity in my own right, you're a different entity in your own right, and so on. From there, we can either 'go small' or 'go large' in our attempts to break out of our self-limiting prison. To 'go small', we can use what some teachers call the 'event perspective' approach, where we look at the phenomena that come and go in our experience in more and more detail. For example, we could work with the sensations of the breath in the deconstructive way I described in a previous article. As we dive further and further into the micro-sensations of the breath, moment to moment, we arrive at a seething flux of phenomena, constantly in motion, nothing fixed, solid or ultimately reliable, and nothing which we can honestly call 'me' or 'mine' - simply a field of rapidly changing sensations. And if we can get down there deeply and clearly enough, we may see our minds constructing the usual 'entities' that we experience out of that sea of ever-changing phenomena, and know clearly that the usual perspective of duality is not 'just how things are', but is simply the mind's projection. To 'go large', we can use the 'mind perspective' instead, where we look at that which is aware of all events. In the cup experiment, we shifted our transparency/opacity up and down the hand, the pen and the cup - this approach is asking us to shift back one step further beyond the hand, to that which is aware of the hand - the source of all experience, the ground of being. The mind itself must become opaque. To do this, we might use a practice like Silent Illumination. As our practice deepens, and we settle into mental and physical stillness, our minds naturally begin to let go of self-imposed concepts and boundaries, and we naturally shift into unification, oneness and finally the ultimate stillness and clarity of the Buddha Nature itself. (Instructions for several approaches to mind perspective practices can be found in a previous article.) This is the promise of the world's great contemplative and spiritual traditions - that we can come to see through our implicit, self-limiting constraints, and arrive at a totally different relationship with the world, one which is more useful (and in a deep sense truer) than the conventional perspective. So what are you waiting for? (Parts of this article were inspired by John Vervaeke's lecture series, Awakening From The Meaning Crisis.)

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

SEARCHAuthorMatt teaches early Buddhist and Zen meditation practices for the benefit of all. May you be happy! Archives

June 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed