Reward-based learning and the BuddhaIn the meditation world, a great deal of emphasis is placed on the present moment. Eckhart Tolle's well-known book is called 'The Power of Now' - it doesn't get much more on-the-nose than that.

The present moment is certainly an important part of spiritual practice, to be sure. But there's another dimension of practice which can sometimes be overlooked if we focus too much on 'right here, right now' - and that's how the practice can help us to change over time. Pre-enlightenment practices of the Buddha-to-be When looking at the discourses in the Pali canon (the records of the earliest period of Buddhist teachings, and generally thought to be closest to the teachings of the historical Buddha), the Buddha doesn't talk much about his personal practice history. Instead, he mostly focuses on giving practice advice tailored to the audience he's addressing. (Notice the resonance with the role of the teacher as discussed in last week's article!) However, in Majjhima Nikaya 19, the Buddha does talk about a practice that he undertook in the early years of his spiritual journey, before reaching awakening. “Bhikkhus, before my enlightenment, while I was still only an unenlightened Bodhisatta, it occurred to me: 'Suppose that I divide my thoughts into two classes. Then I set on one side thoughts of sensual desire, thoughts of ill will, and thoughts of cruelty, and I set on the other side thoughts of renunciation, thoughts of non-ill will, and thoughts of non-cruelty.' (Readers familiar with the Eightfold Path will note that the Buddha-to-be chose to divide up his thoughts based on those in line with Right Intention and those not in line with it.) The basic premise here is that thoughts can be conceptually divided into two categories: those which support our growth in the directions we wish to move, and those which don't. This is potentially helpful in two ways. Firstly, by getting clear about the types of thoughts we have, we start to develop an awareness of how much time we spend engaging in mental activity that is beneficial and supportive of our aims in life, and how much we spend doing the exact opposite! Then, secondly, we can start to do something about it. But what should we do, and how? Well, let's see what the Buddha has to say. Continuing with MN19: "As I abided thus, diligent, ardent, and resolute, a thought of sensual desire arose in me. I understood thus: 'This thought of sensual desire has arisen in me. This leads to my own affliction, to others' affliction, and to the affliction of both; it obstructs wisdom, causes difficulties, and leads away from Nibbāna.’" (The discourse later goes on to describe the same process for thoughts of ill will and thoughts of cruelty, but to keep things simple we'll focus on thoughts on sensual desire here.) What's being described here is a mindfulness practice - specifically, mindfulness of thoughts. Typically, when thoughts arise in meditation, we simply let them come and go, doing our best not to pay too much attention to them, perhaps remaining focused on an object such as the breath or the body sensations. In this case, though, the practice is actually to look at the thought carefully - but without being drawn into the story associated with the content of the thought. That's tricky! The reason that most meditation practices work with something other than thoughts is because they're so 'sticky' - a thought comes up about something disagreeable that happened to us, and before we know it we're replaying the memory and getting annoyed all over again. At this point, the meditation practice has usually been lost, swept away in the tidal wave of thoughts and emotions associated with the story. Nevertheless, if we're able to pay attention to our thoughts without getting drawn into them (which is possible, with practice), then we start to notice some interesting things. Over time, we can observe where our thoughts lead us. In the example above, the Buddha describes noticing the arising of a thought of sensual desire. We might think 'Well, what's wrong with that? What's wrong with wanting something nice?' Maybe nothing - but you should check it out for yourself! In my case, I've noticed that thoughts of sensual desire often over-emphasise the positive aspects of the experience that I'm craving, and brush under the carpet the negative side. When I see a chocolate cookie, the pleasure I'll experience when I taste it is immediately apparent to me... and I tend not to think about the regret I'll feel when I weigh in the next morning and the scale has bad news for me. There's also a subtler detail that has taken a lot longer for me to notice - which is that, after I eat a sugary snack, my body actually feels pretty bad not long after. The taste is great at first, but it leaves a kind of slightly unpleasant residue in my mouth afterwards - which, ironically, my habits tell me can most easily be assuaged by eating another cookie. Eating too much sugar can also lead to a sugar high, in which both my mind and body become slightly agitated and uncomfortable. It's not a big deal, easily missed - usually missed, because I've gone straight from eating the cookie to focusing on something else - but it's there in the background of my experience nonetheless, making me feel 5% crappier than if I hadn't eaten the cookie in the first place. Humans have a tremendous capacity for selective awareness. I know I do! It's easy to focus on the positive aspects of an unhealthy behaviour - the taste of the cookie, the rush of the cigarette, the thrill of doing something dangerous - and ignore the negative aspects. But something interesting starts to happen if we're able to bring the light of awareness to the totality of a situation. Slowly but surely, we arrive at a more balanced view of what's going on - the good and the bad. This can help to take the sting out of very difficult experiences, as we notice the silver lining to the cloud, and it can also help to reveal the dark side of patterns like unhealthy pleasure-seeking. The Buddha describes coming to this exact realisation. By examining his own thoughts of sensual desire, he discovered that, ultimately, they led to his own 'affliction' - a strong word, perhaps, but the point is that he realised that, in the long run, chasing material sensual pleasures wasn't taking him where he wanted to go - and, looking more broadly, the same pattern seemed to apply to the people around him as well. Becoming disillusioned - which isn't as bad as it sounds! One slightly annoying feature of insight meditation is that it's possible to see something once, twice or even a few times without it really having much impact. Perhaps we notice 'Gosh, things really are impermanent, aren't they?', and yet we're still left with a sense of 'Yeah, but so what?' In just the same way, it's quite possible to notice the negative aspects of some of our behavioural patterns, and to accept fully on the intellectual level that this is something we should probably stop doing... and yet the behaviour still doesn't change. (Unfortunately, I speak from experience!) I once heard a teacher compare insight meditation to a process of conducting a survey. You ask a couple of people what they think about something, and you get a bit of information - but it isn't really enough to draw conclusions from. You ask a thousand people, maybe a pattern starts to emerge - you're starting to get somewhere, but there's still a way to go. By the time you've asked a million people, you've now got a pretty solid basis to draw conclusions. In the same way, each time we observe our experience, we're gathering evidence. Maybe that first glimpse of impermanence doesn't seem like a big deal - OK, you definitely noticed something, but you've spent a lifetime building up the implicit world view of permanence and solidity, and it'll take more than a few experiences of impermanence to really make a difference. But if you keep at it, then sooner or later the sheer weight of evidence you've accumulated becomes undeniable - and that's when things flip around, and your world view changes. And the same applies to behaviour change. The Buddha goes on: "When I considered: 'This leads to my own affliction,' it subsided in me; when I considered: ‘This leads to others’ affliction,’ it subsided in me; when I considered: ‘This leads to the affliction of both,’ it subsided in me; when I considered: ‘This obstructs wisdom, causes difficulties, and leads away from Nibbāna,’ it subsided in me. Whenever a thought of sensual desire arose in me, I abandoned it, removed it, did away with it." By examining his thoughts of sensual desire and noticing that they consistently led away from where he wanted to go, those thoughts began to subside. The Buddha realised that the promise of lasting happiness offered by those thoughts of sensual desire was an illusion - and so he became disillusioned. The experience of disillusionment is generally not a happy one. I experienced a fairly significant disillusionment recently, and it sucked! But - as a friend was kind enough to point out at the time - disillusionment means letting go of an illusion - something that wasn't real in the first place. It's uncomfortable and embarrassing to realise that we've been operating under a false impression all this time, but in the long run it means we're moving into closer alignment with the truth of things - and that's ultimately what this path is all about. And, just like a magic trick that's been seen through, when we become disillusioned with something, it loses its power over us. In the Buddha's case, when he deeply understood that his thoughts of sensual desire weren't taking him where he wanted to go, the thoughts subsided. As we can see, this wasn't an immediate process, like flicking a light switch - the thoughts continued to come up for a while, but each time they did, he reflected on negative consequences, and again those thoughts lost their power. Reward-based learning and habit change The understanding of psychology has undergone some pretty significant changes since the time of the Buddha 2,500 years ago, and this can sometimes lead to a bit of a language barrier when trying to map traditional teachings on to modern concepts. (For example, you might be surprised to hear that there's no Pali word for 'emotion', since the concept didn't exist back then - perhaps that's even shocking, given how central emotion is to our modern understanding of human behaviour.) Nevertheless, MN19 is describing a deep truth about human experience - and one which is now being validated and fleshed out in modern terms by scientists. There's a biological mechanism called 'reward-based learning' (or simply 'reward learning') which is key to how living beings learn to navigate their environment. At the simplest level, 'if it feels good, I should do it again; if it feels bad, I shouldn't do it again'. It hurts to stub your toe, so you learn to try to avoid doing that - which means that, overall, you're less likely to damage yourself. It feels good to spend time with friends, so you learn to do that - which means that humans tend to build communities that support each other and help us to survive by pooling our skills and resources. And so on. While this is probably an oversimplification (if you're more knowledgeable on the science of all this and want to fill in some of the blanks, please leave a comment below!), we can start to see both where our bad habits come from, and how bringing clear awareness to an experience (including its downstream consequences) can lead to behavioural change. We start with that first bite of the cookie. It's sugary - and that's good, because our bodies use sugar as an energy source. Unfortunately we evolved in an environment which didn't have shops selling chocolate on every corner, and so we're biologically geared to load up on resources when they're available, since we might not get to eat tomorrow. That ingrained biological response is then exploited by junk food manufacturers, who take great care to design sweet treats that are as appealing as possible to our old-fashioned instincts. So we take that first bite - and it's good! Reeeeeally good! The behaviour of taking a bite of a cookie leads to a significant positive reward - and by the time we've eaten the whole thing, we've repeated that pattern a few times. Already, our brains are starting to learn 'eating cookie = good, more please!' But this only works if we do what we usually do, which is focus on the pleasant aspects of the experience and distract ourselves (whether deliberately or not) from the unpleasant aspects. If we instead bring mindfulness to the whole experience, then the overall 'reward' of the activity starts to go down - because now we're noticing not just that initial high but then the low that follows it. And if we do this repeatedly (that 'gathering evidence' process I mentioned above), then we can recalibrate our brains to the new reward level. We start to realise that, although the cookie still looks good, actually there are some significant downsides to it as well. Maybe we'll just have one today, rather than the whole bag - or maybe we'll just get a cup of tea instead. For more on reward-based learning, habit change and mindfulness, check out the work of Dr Judson Brewer, who uses mindful approaches inspired by the early Buddhist suttas to help people to quit smoking and make other positive behavioural changes. Closing on a tangent: a few thoughts on pleasure, happiness and the spiritual life It's pretty common for people to object to the idea that sensual desire could be viewed in a negative light. To Western audiences, it smacks of joyless puritanism, asceticism for its own sake, an anti-life philosophy. It's usually easier for people to see why thoughts of ill will and cruelty should be abandoned - but what's wrong with pleasure? One response to this is to say that it isn't about eliminating pleasure from our lives, but about coming to a more balanced appreciation of what's going on. As I've outlined above, eating a cookie is neither 100% positive or 100% negative. It tastes great - that's a nice thing! But it also has some negative consequences - and if we're focusing only on the positive and ignoring the negative, we're deluding ourselves as to what's really going on. When we have a more balanced appreciation of the whole picture, we might still choose to eat the cookie - but we'll be making that decision with our eyes open, rather than sleepwalking into it because we're too distracted by the promise of pleasure. A slightly more sophisticated version of this argument (which is admittedly harder to justify in the context of MN19 above) is that we aren't necessarily trying to eliminate sensual desire, but rather to be free from it. What does that mean? It means that we have a choice in the matter. I've had times in my life when I've been so hooked on caffeine that at 11am every day my legs carry me to the shop at work and my hands grab the Coke bottle out of the fridge and pay for it with my credit card without my conscious intervention - I can watch the process happening, vaguely aware on some level that I'd been planning to cut down on my caffeine intake, yet the habit is so strong that it feels like I'm watching it play out on a TV screen. When we're really hooked on some kind of sensual desire, we really don't have much say in the matter - we're at the mercy of our habits and our environment. Part of the reason for cultivating mindfulness is to bring some agency back into the picture - to open up a space in which we can see our impulses come up and decide whether to act on them. Both of these answers lead to an approach which is eminently compatible with being fully 'in the world'. We continue to have families and friends, jobs and hobbies; and we continue to do things just because they're fun - but this is balanced by the cultivation of mindfulness and a gradually deepening awareness of the full story of how these things affect us. It becomes easier to notice when a 'harmless fun' activity is starting to get problematic - that addictive mobile phone game is starting to take up a bit too much time in the morning, and we're beginning to arrive late for work, or we no longer have enough time to make a healthy packed lunch to take with us, so instead we're going to the shops and buying junk food instead. If there's no problem, there's no problem - but when there's a problem, we're more likely to spot it, and to have sufficient presence of mind to steer ourselves back on track. This is fine so far as it goes. But you won't have to look far to find spiritual teachers and philosophers advocating something much stronger - a deep renunciation of the world, a total cutting off of 'frivolous' activities in favour of solitude and spiritual pursuits. What's going on here? First, I should say that I'm not a monk and have never been one, so I can't really say what the monastic life is like from personal experience. The closest I've come is doing residential meditation retreats, the longest of which have been two month-long retreats at Cloud Mountain Retreat Center in the U.S. - but I think that's long enough to give me a sense of what the more thoroughly renunciate life offers. I've previously offered a model of 'excitation and stimulation' to describe the process of 'settling the mind' in meditation. The basic idea is that, at any given moment, we have some internal level of 'excitation' - from being utterly calm to being excited, terrified or stressed out - and that, in order to meditate effectively, we need to find a meditation technique which offers a level of 'stimulation' (how interesting/engaging/active/busy the technique is) which approximately matches our current level of excitation. If the technique isn't stimulating enough, we get bored and can't stay with it. If it's too stimulating, we actually disturb our minds rather than settling them. Well, it turns out that when you get the mind settled enough - which typically happens for me after a few days on a residential retreat - it feels really, really good. Not 'cookies and ice cream' good, but a different kind of experience - a subtle, beautiful, deeply profound contentment. Like the taste of a mango, you have to have experienced it to know what I'm talking about. But the key point is that, when you're there, it's very obvious that it's a really, really good place to be, and that all of the usual pleasure-seeking activities of your busy life don't come close. And a very natural thought that comes up at such a time is 'Why would I ever want to go back to how things were before?' Because here's the thing - accessing that kind of peace really isn't compatible with going to the cinema at weekends and playing video games in the evenings. Those activities are so stimulating - being aimed at people who are living highly stimulating lives in our busy modern society - that they're utterly destructive to the peace of mind that comes from solitude. Whether or not you've experienced the kind of deep peace that the renunciate sages are pointing to, it isn't so outlandish to believe that if we want to take something to its farthest, deepest extents, we're going to have to make some sacrifices along the way. Suppose you want to play the piano. If you play for ten minutes two or three times a week, the chances are you'll have some fun but you'll never play to a sold-out crowd at the Royal Albert Hall. If you want to be a professional concert pianist, you're most likely looking at practising for many hours every day - and you'll also have to give up any activities that would interfere with your piano playing (for example, anything which has a serious risk of injury to the hands). I remember one point when I was practising both Kung Fu and Tai Chi with the same teacher, and I was having some trouble taking my Tai Chi to the next level of subtlety due to habitual muscular tension in my wrists. My teacher nodded and said 'Yeah, that's a Kung Fu thing, unfortunately.' At that moment I knew I'd have to give up Kung Fu if I wanted my Tai Chi to go deeper - not because Kung Fu was bad and Tai Chi was good, but simply because they were pulling me in opposite directions. (I quit Kung Fu - and while I miss it sometimes, overall I don't regret my decision. Deepening my Tai Chi was very much the direction I wanted to go, and my practice has developed significantly in the years since then.) Getting back to the spiritual life, in the same way as the Tai Chi-Kung Fu example, it isn't that worldly pleasures are intrinsically bad - but, past a certain point, if you want to go as deep as possible in terms of deep states of peace and tranquility, you can't have it both ways. Either you pursue the path of solitude in a very dedicated way, sacrificing a great deal of modern life in the process, or you accept that by remaining embedded in the world you're only going to touch into that place of peace deeply on long retreats. Which is it to be? And I suspect that the way we each answer that question is what makes the difference between those who choose to pursue a truly renunciate lifestyle and those who don't. I have friends who are very strongly drawn to that way of life above and beyond everything else - but I'm not one of them. I'm drawn to the world. I enjoy learning complex technical things and solving problems. I want to play a hands-on role in helping people - and not just in the spiritual world, but in wider society as well. So I have a day job in which I try to solve technical problems in a way that benefits the wider society. I also have hobbies and interests - I really like science fiction (as you can probably tell from some of the references that make their way into these articles), I enjoy writing, making music, playing games with my friends (we just started a Cyberpunk RED campaign that I'm very excited about - note, excited, not peaceful and content!), going to the cinema and so on. I also have a dedicated daily spiritual practice - which brings me the kinds of benefits I've outlined above and more - and at least a couple of times a year I go on retreat, and reconnect with that deeper place of stillness. My personal sense - and I could be totally wrong - is that some degree of that peace and stability does work its way into daily life, maintained by my daily practice and deepened by my time on retreat. And that's enough for me. I find that it's worth the trade-off to give up the full depth of contentment that might be available if I had a more renunciate lifestyle, in order to remain more fully in the world, committed to making whatever small contribution I can to our modern society from within rather than leaving it behind - and enjoying some conventional pleasures along the way too. But that's just me. I don't say this to criticise anyone else's lifestyle choices! Maybe meditation helps you but going on a retreat is a step too far - great, meditation helps you! Or maybe you're making that transition to the more fully renunciate way of life - good for you. Sometimes I wish I could join you! May you find your own path to happiness - whatever that looks like. Postscript: as synchronicity would have it, Zen teacher Domyo Burk has recently uploaded two podcasts on the subject of renunciation and the household life. Check them out: part 1 and part 2.

0 Comments

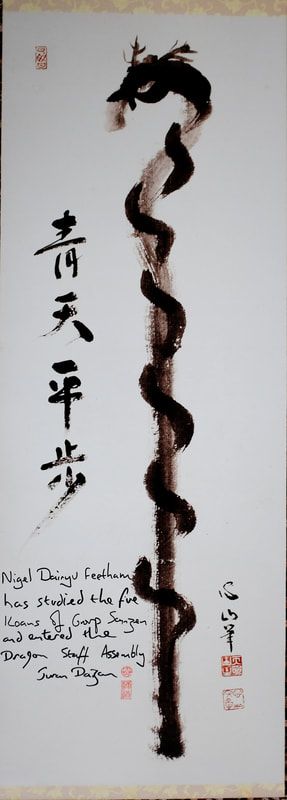

The winding road of Zen practiceThe image above is a painting of a staff transforming into a dragon, symbolising Zen awakening. Copies of this scroll have historically been given to Zen students who have met a certain bar in their practice. Within Zenways, my Zen sangha, it was the practice at one point to give a copy of this scroll to students who'd studied all five Group Sanzen koans, as you can see from Daizan's inscription above. The image is taken from Nigel Feetham's website, used without permission.

This week we're looking at case 44 in the Gateless Barrier, simply titled 'A Staff'. As usual, on the face of it, it doesn't seem to make much sense - but once we get into the symbolism involved, it'll hopefully become a bit clearer.

Giving you a staff: formlessness to form Zen teachers often have a staff, which represents their role as a teacher. More generally, the staff represents a method, a form of practice. When we are first drawn to the spiritual life, we begin in a state of 'formlessness'. Perhaps we have an aspiration - to be a better person, to achieve enlightenment, to find peace of mind - but unless we have a practice of some sort - something to do - it's difficult to make that aspiration a reality in our lives. Traditions like Zen and early Buddhism offer us a whole variety of methods of practice. Perhaps we're drawn to exploring a spiritual question through koan study, or perhaps the holistic nature of the Eightfold Path appeals to us as a way of life. One way or another, in the early stages, we very much need some kind of 'form' - a practice or set of practices that we can undertake consistently over a period of time (weeks, months, years). Here, a teacher is very helpful. Of course we can concoct our own spiritual path, either from a single tradition or by blending together techniques from a variety of sources (just like I tried to 'teach myself' to play the guitar when I was a teenager!). But it tends to be much easier and more effective to find a teacher that we're willing to work with - in an ideal world, a teacher has already travelled at least some of the path that interests you, and they can help to save you time by pointing out the common pitfalls and correcting mistakes that are easily seen from the 'outside' but more difficult to spot from the 'inside'. Different teachers take different approaches to providing 'form' for the student. Some teachers develop systems and curriculums which encapsulate what that teacher understands the Dhamma to be. Other teachers prefer to guide students on a more individual basis, trying to find the forms which best suit that individual. I tend more toward the latter, although I had a bit of a stab at system-building here - in a nutshell, I generally recommend that people have a practice that combines concentration, insight, heart-opening and energetic cultivation, with a strong ethical foundation. In any case, when it's working well, the teacher will be supporting the student to develop in a way that's working well for them. That's the first part of the koan here - 'If you have a staff, I will give you a staff.' At least the way I understand Dhamma teaching, it isn't my job to tell you how to live your life; rather, it's my job to help you work within the life you already have and do my best to support and accelerate your progress. As such, I'm not looking at you as a person with no staff who needs to be given my staff (which is, of course, the best of all staffs) - rather, I recognise that you already have a staff, and I'm just supplementing what you already have, to the best of my limited ability. Taking your staff away: form to formlessness In the fullness of time, practice begins to mature. In the early stages, you're learning 'how to' - you're getting the basic instructions for a practice and figuring out how to do it in the most basic sense. As we continue to practise over the months and years, however, a transition takes place. At the beginning, we're working with a technique that someone else has given us. In the fullness of time, however, the practice becomes our own. We develop our own relationship to it, our own sense of how the practice works, and how best to engage with it in this moment, with this particular set of conditions. This transition reflects a process of integration - a blurring of the boundaries between 'this technique' and 'me'. Gradually, the separation between the two disappears. My daily Silent Illumination practice is no longer a fancy Zen meditation performed with much ceremony and specialness; it's simply how I start each day, sitting quietly and watching my experience. At times I'll find myself sitting in the same way on train or coach journeys, simply observing. There's no real distinction between 'formal practice' and 'informal practice' - resting in awareness has simply become one expression of my life, which emerges when the conditions are right. (Perhaps that sounds a bit grandiose! I don't mean to suggest that I'm incredibly advanced or have an amazing practice, or anything like that. I'm just trying to highlight the way in which my relationship to my practice has changed over the years.) In some ways, this period of practice can even bring up a bit of sadness. The novelty has very much worn off! Indeed, there can be a sense that practice 'used to be more interesting' - particularly when things are first taking off, it's quite common to have lots of deep insights, and to start to feel a bit special as a result. 'Look at me!', you might think. 'All these other suckers don't understand anything, but I know what the Buddha was getting at, I understand all these Zen texts!' The technical term for this stage of practice is 'the stink of Zen'. My teacher's teacher, Shinzan Roshi, would sometimes hold his nose and say 'stinky, stinky!' if people were getting a bit too impressed with themselves. It's an exciting period, but it's also an immature one, and a responsible teacher will typically do their best to bring the student's feet back down to the ground. And that's what the second part of the koan indicates - 'If you have no staff, I will take your staff away'. Early on, a very intense fascination with and attraction to the forms of practice can be very helpful - but past a certain point it simply becomes another kind of attachment, another ego support to make ourselves feel special because of all of our wonderful insights. In the long run, the spiritual path is all about letting go - and that includes letting go of the story of what a great meditator we are. And thus we return again to formlessness - letting go of our attachment to specific techniques, allowing our practice to integrate itself so completely that there's no distinction between 'practising' and 'not practising'. This is a long and difficult journey, and perhaps one that takes a whole lifetime to 'complete' - but it's also a rewarding one. Along the way, we learn the true value of these practices as they manifest in our own lives, not as they're portrayed in ancient texts from other cultures around the world. Gradually, we return to formlessness; this second formlessness is both fundamentally different to, and fundamentally the same as, the first formlessness at the beginning of our practice. As T.S. Eliot put it: We shall not cease from exploration And the end of all our exploring Will be to arrive where we started And know the place for the first time. Through the unknown, remembered gate When the last of earth left to discover Is that which was the beginning; At the source of the longest river The voice of the hidden waterfall And the children in the apple-tree Not known, because not looked for But heard, half-heard, in the stillness Between two waves of the sea. Or, in the words of the great Zen master Bruce Lee: Before I learned the art, a punch was just a punch, and a kick, just a kick. After I learned the art, a punch was no longer a punch, a kick, no longer a kick. Now that I understand the art, a punch is just a punch and a kick is just a kick. Where are you on this journey? Do you have a staff, and if so, do you have the support of a teacher who can ensure that your staff is in the best shape it can be? Or is it time to let go of your staff - and if so, do you have a teacher on hand to point out when you're reflexively grasping at the familiar, comfortable staff that's brought you so far, and to prise it gently out of your grasp? Training the mind

This article is the final one in an eight-part series on the Eightfold Path, a core teaching from early Buddhism. I introduced the Eightfold Path in the first article in the series, so go back and check that out if you haven't heard of it before. (You can find links to all the articles in this series on the index page in the 'Buddhist theory' section.)

This week we're taking a look at the eighth factor of the path, right concentration. In the quotation above, the Buddha explains right concentration as the practice of the four jhanas - altered states of consciousness which we can train ourselves to enter through diligent practice. I've written about jhana several times before (giving detailed instructions here, setting the jhanas in the context of the wider path here, and looking at the so-called 'higher' or 'formless' jhanas here), so rather than repeat that material here, I'll instead try to give a sense of my current understanding of what the jhanas actually are, what function they serve in the context of the Eightfold Path, and then take a look at how some other traditions have arrived at different solutions to the same problems. What actually are the jhanas anyway? The jhanas are altered states of consciousness that can be entered through meditation. Each has a number of associated 'factors', but at a high level, the first jhana is a state of strong bodily bliss, the second jhana is a state of strong emotional joy or happiness, the third jhana is a state of quiet contentment, and the fourth jhana is a state of deep peace and equanimity. (I go into much more detail about the jhana factors here.) The jhanas are sometimes described as 'concentration states', and they're strongly associated with samadhi practice, often called 'concentration meditation'. The basic idea with samadhi practice is to rest your attention on an object, and when you notice that your mind has wandered, let go of the distraction, relax, and come back to the object. Rinse and repeat until the mind wanders less and less - there's often a kind of tipping point when you notice that you aren't really getting distracted any more (a state which my teacher Leigh Brasington would call 'access concentration'). Following the instructions from this article, you can then enter the first jhana - at least, the way Leigh and I teach it. It turns out that this is not the only interpretation of jhana. Some teachers require a much, much deeper level of concentration than what's described above before they're willing to call the resulting state 'jhana' - see the work of teachers like Pa Auk Sayadaw, Tina Rasmussen and Beth Upton for examples. And other teachers require less concentration, such as Bhante Vimalaramsi, because they want to use their version of the jhanas to do things that are difficult to do when the mind is more deeply concentrated. And to cap it all, every teacher worth their salt will tell you that their version of the jhanas is what the Buddha really taught, accept no imitations! What's a meditator to do? My impression now, after ten years of jhana practice in Leigh's style and having dabbled a bit with a few other approaches (both a bit lighter and a bit deeper - I haven't gone really deep, so if you'll only accept the deepest of the deep, you can stop reading now!), is that it isn't really accurate to call the jhanas 'concentration states'. I say that because I can enter an altered state of consciousness which is recognisably one of the jhanas at will, without having first done the preparatory practice to stabilise my mind and build up concentration. The resulting state is weak, unclear and easily lost, but is still clearly whichever jhana I was aiming for - it's the same state, just with substantially less concentration. If I build up more concentration first, I go into a version of the jhana which looks exactly like what Leigh taught me. If I build up even more concentration first, the phenomenology starts to resemble some of the deeper jhanas taught by other teachers. And I presume that if I built up incredibly strong concentration, I would end up in the version of the jhanas taught by Pa Auk and friends. So if the jhanas aren't 'concentration states', why do they come under the heading of 'right concentration', and why are they taught on 'concentration retreats'? Well, for one, it's very helpful to have a concentrated mind to learn the jhanas in the first place. When you're first learning the practice, you're asking your mind to go somewhere unfamiliar, and that's a difficult thing to do. It's very helpful to have stabilised the mind beforehand so that it's less prone to wandering - otherwise you'll probably fall out of the state before you've had a chance to get used to it. Once you've become more familiar with the jhana, you'll probably find that you can intuitively 'incline' your mind toward it, and enter the jhana with less concentration than it took when you were first learning. Secondly, and more relevantly for the Eightfold Path, the jhanas are also a fabulous way to deepen your concentration. Fundamentally, the jhanas are states of enhanced wellbeing - they're nice states that the mind likes to inhabit. Bliss, joy, contentment, peace - these are good places to be, so once the mind figures out how to find them, it gets easier to stay there for long periods. While you're in the jhana, you're focused on the qualities of the jhana itself, and so the mind will tend to be even less prone to distraction than it was previously, and thus become more deeply concentrated. The stillness and clarity of the mind coming out of the fourth jhana is typically much stronger than the stillness and clarity of a mind which has spent the same length of time in access concentration. So concentration helps us to find the jhanas in the first place, and then in turn the jhanas help us to deepen our concentration further. That sounds like a solid definition of 'right concentration' to me. Other interpretations of right concentration As I mentioned above, some teachers have extremely high standards for jhana - high enough that most people don't have the time or even the capacity to develop concentration deep enough to meet their requirements. Perhaps as a result, you'll now find many teachers who will say that jhana isn't necessary at all, or even that it's a bad idea - just another cause for attachment. (To that I would say - can you get attached to the jhanas and start using them just to get high? Sure. Don't do that. There are lots of ways to misuse spiritual practice, but that doesn't mean you should reject the whole thing. That's like saying that because you might burn yourself on a flame, everyone should eat all their food raw all the time to avoid the terrible risk of getting burned. Raw food is fine if that's what you're into, but you could alternatively learn not to burn yourself and then enjoy cooked food. To each their own.) At the extreme end of the spectrum, you'll find teachers offering what's usually called 'dry insight'. This approach doesn't have any 'concentration practice' per se - students will simply go directly into an ***insight practice. (See, for example, Mahasi noting.) But now these teachers have a problem, because 'right concentration' is one of the aspects of the Eightfold Path, and they've deleted the concentration practice. Their solution is to emphasise 'momentary concentration', or 'khanika samadhi'. This is the type of concentration needed to stay focused on a complex, moving task - such as noting the arising and/or passing away of every sensation in your sensory experience. By comparison, the type of concentration I described above - putting your attention on one object and staying with it for a prolonged period - can be called 'one-pointed samadhi'. The noting practice is not one-pointed - since you're moving your attention from one sensation to another in order to note it - but you do nevertheless stay engaged in the (moving) practice for an extended period of time, so there's a kind of 'concentration' there. The 'momentary concentration' approach has a couple of advantages. First, it's simpler - you only have one type of practice to do (your insight practice), rather than two. Second, some people have a really hard time focusing the mind, and so find one-pointed samadhi practice to be pretty unbearable. Being given permission to 'skip' the concentration can actually be really helpful in a circumstance like that, because it allows the practitioner to focus on their strengths rather than having to suffer through their weaknesses. Another, more middle-ground, approach to redefining 'right concentration' is to make some effort to develop one-pointed concentration, but to omit any mention of jhana. (See, for example, the concentration practice in the Goenka tradition, which builds one-pointed concentration on the breath without referencing jhana at all.) Again, this has some advantages. Most practitioners will develop more concentration this way than through the 'dry insight' route, which will in turn make their insight practice deeper and more impactful. And by omitting any mention of jhanas, there's no need to learn altered states of consciousness which - depending on whose definition you're using - may be difficult or even unattainable. Needless to say, I'm a fan of the jhanas! They really helped me, and I've seen them help plenty of other people too. But I've also seen people do well in other styles of practice too, so - despite the quotation at the top of the article - I don't want to give the impression that I think you'll go straight to Buddhist hell if you don't learn the jhanas right away. (Even so, I'd encourage you to give them a try! Come on a retreat with Leigh or me and see what happens. I'm currently hoping to arrange some retreats in Europe over the next few years, and I'd like some people to come to them - maybe you could help me out here?) What does Zen make of all this? Amusingly enough, although the words 'Zen' and 'jhana' actually come from the same root (Pali 'jhana' -> Sanskrit 'dhyana' -> Chinese 'chan'na', shortened to 'chan' -> Japanese 'zen'), the Zen tradition tends not to teach the jhanas, at least not openly. It's actually very common for meditators of all traditions to stumble into the jhanas - I recently met a guy who said he was interested in them but had no idea how to get there, and when I asked him about his practice it was clear that he'd been in at least the first jhana many times without recognising it. In the case of Zen, though, the teacher will typically show little interest in reports of altered states of consciousness, saying something like 'Oh yes, that happens from time to time, just let it come and go like everything else.' Within the Soto tradition there's a much greater emphasis on 'ordinariness' and integration into daily life, while Rinzai Zennies are usually more interested in insight, kensho and satori than altered states which are not themselves intrinsically insight-producing. (Another risk of jhana is that people might mistake them for insights, because 'look, something's happening!' - again, in my mind, that's an argument in favour of teaching the jhanas openly, so that practitioners know what's happening, rather than concealing or demonising them, but whatever.) As far as Zen is concerned, though, it's also worth noting that there's perhaps a little less need for a jhana practice in that context than in the early Buddhist context. Many of the insight practices in early Buddhism (and the Theravada tradition that developed out of it) place great emphasis on noticing impermanence and unreliability - and it can be unsettling or even destabilising to notice these things directly. Spending time cultivating the jhanas sharpens the mind, allowing you to notice impermanence more easily, but also stabilises it, allowing you to face aspects of your experience which would be unnerving or upsetting under normal circumstances, but which are easier to bear with the equanimity cultivated through samadhi. So you end up with two practices: samadhi to stabilise the mind, then insight which unsettles it, then back to samadhi to restore the stability, then back to insight to keep digging deeper, and so on. By comparison, Zen's two major practices are Silent Illumination and working with a koan. Silent Illumination can actually be defined as a balance of stillness (the silence, aka samadhi) and clarity (the illumination, aka insight). We stabilise our attention on the totality of the present moment and allow it to reveal itself to us more and more deeply - we aren't particularly focusing on impermanence or unreliability, or deconstructing anything, we're not actually doing anything apart from simply remaining aware. Individual moments of insight may have a destabilising effect, but the practice itself doesn't have an intrinsically abrading effect on the mind's calmness - quite the opposite. Working with a koan can be a bumpier process, especially at first, when asking the question is bringing up all kinds of thoughts and ideas. But the key is that we don't do anything with whatever comes up - we simply notice it, let it go, and then ask the question again. Over time this has a kind of 'winnowing' effect, ultimately allowing the mind to become focused on the questioning itself rather than whatever 'answers' might be coming up. This focus on 'wanting to know' (sometimes called Great Doubt in the Zen tradition) should be balanced with a kind of radical openness, a willingness to receive an answer in any form, from any direction, at any moment. Thus, again, we have a balance of stillness (the focus on the questioning) and clarity (the receptivity to whatever may come up) - incorporating both 'concentration' and 'insight' into one practice. So what exactly is 'right concentration'? Well, if you're a purist, and you want to go with what the Buddha is reported to have said in the Pali Canon, then click on the link at the top of this article and check out Samyutta Nikaya 45.8 - and you'll find right concentration defined in terms of the four jhanas. You can use the resources on this website, or buy Leigh Brasington's excellent book Right Concentration, or (best of all) come on a retreat with Leigh or me and give it a go. (In fact, you can do any of those things even if you aren't a purist!) If you're more inclined to the Zen way of things, then the key is to ensure that your practice includes both aspects - the silence and the illumination, the questioning and the receptivity. More generally, any amount of concentration, of any sort, is likely to strengthen your insight practice - so even if you aren't interested in jhana, it's worth taking a look at how concentration might manifest itself in your practice. It's in the Eightfold Path for a reason! The end of the Eightfold Path? So, this brings us to the end of this article, and this series. Like I said at the start, though, the Eightfold Path isn't really sequential - you don't start with right view or end with right concentration. All eight aspects are to be practised as part of one holistic path. Different aspects will come to the fore at different times - but they're all helpful in their own ways. It can be interesting to reflect on this from time to time - are there aspects of the path where you're stronger, aspects which don't get so much attention? What might happen if you spent some time focusing on a neglected aspect of the path? And what does each aspect mean to you - not just in terms of the 'textbook' definition, but as an actual, living practice? How might the Eightfold Path manifest itself in your life? Finding a way forward when none of your options are viable

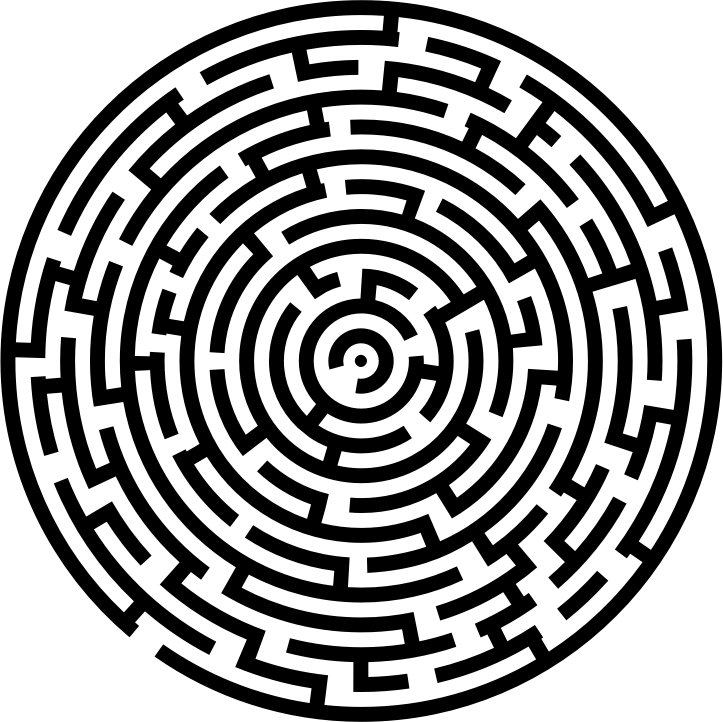

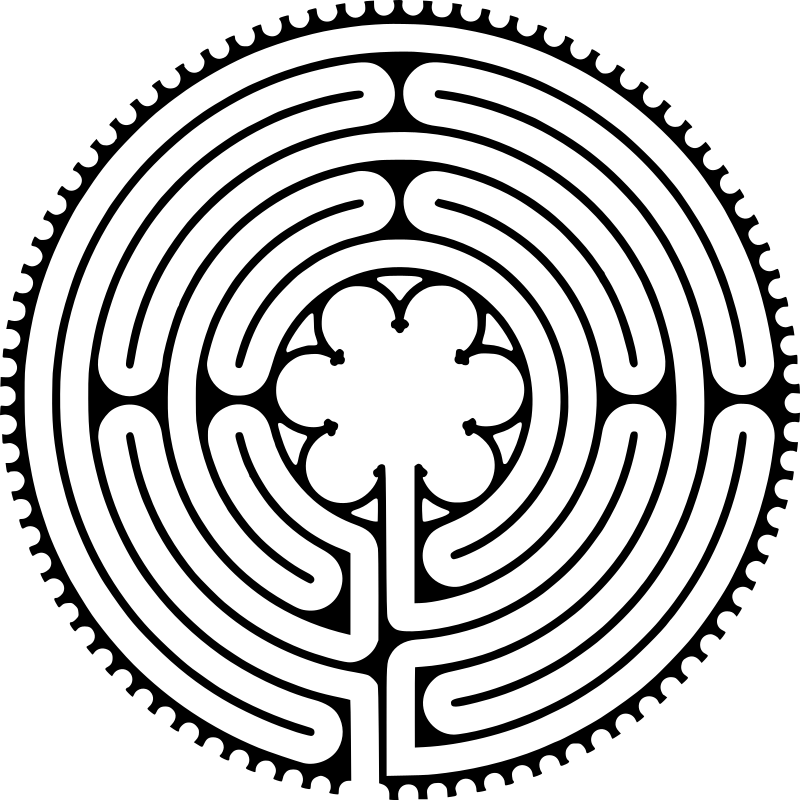

This week we're looking at case 43 in the Gateless Barrier. Regular readers of the blog might notice a striking similarity with the key moment in case 40, and you'd be right to do so - it's very similar. Rather than repeat the points I made in my discussion of that koan, though, today we'll go in a different direction (in other words, don't feel that you have to go and read that article first!). Koans are annoying! Zen is famous for its use of koans - short vignettes often describing an encounter between a teacher and a student in which some pivotal question is posed, or insight is arrived at in some other way. At first glance, koans often appear totally nonsensical, and some people will tell you that that's exactly what they are - pure nonsense, designed to confuse and frustrate your thinking mind, with no intrinsic meaning beyond that. In general, I disagree with that view - as I've attempted to show over the course of this series of articles (which is almost complete now - only five more koans to go after this one!), koans are often filled with cultural and literary references that would have been well understood by practitioners of the era but which are now totally mysterious to modern readers until they're explained to us. (Imagine a Zen teaching story made up entirely of Star Wars references, and how that would look to a 12th century Chinese Zen practitioner!) Nevertheless, although I wouldn't say that koans are total nonsense, it absolutely is true that koans are intended to take us beyond the purview of the analytical mind. You can see this even in the basic instructions for koan practice - students are advised not to think about the koan and try to 'figure out' the answer in a logical manner. Instead, we 'throw' the koan into our minds, like a stone into a lake, and then simply observe to see what splashes up in the air in response. If we do this for long enough, we'll notice something interesting. (Extending the lake analogy, we might say that Silent Illumination practice is a different means to the same end - in Silent Illumination, we simply allow the water to become still and clear all by itself, deliberately avoiding doing anything that might stir it up, until we can finally see all the way to the bottom of the lake.) Of course, despite the standard instructions, many people (myself included) will find themselves thinking about the koan and trying to solve it like a riddle or a logic puzzle. This is a big problem for me - I've been a problem-solver my whole life (it got me good marks at school and a decent salary in adulthood), and I'll often find myself trying to 'figure out' something that really doesn't need to be figured out at all, just because it's a familiar activity that results in a periodic burst of pleasure when whatever puzzle I'm chewing over suddenly resolves itself. (As an aside, it's interesting to note that the source of that pleasure is actually relief from the mild stress of wrestling with an unsolved problem. In other words, I'm chasing those brief hits of pleasure, but in doing so I'm actually subjecting myself to much longer stretches of discomfort. Many of our habits are like this!) So a koan like this one - in which we're offered a binary choice, and explicitly told that neither option is acceptable - is a good one for people like myself who have this tendency to overthinking; there's simply no way out using logic, so in order to progress we have to find another approach entirely. The present koan gives us an analogy for this kind of over-reliance on the thinking mind - Shoushan compares it to 'clinging' to the bamboo stick. What happens if we try to cling to a bamboo stick in real life, holding it as tightly as we can? Sooner or later, our muscles get tired, and spontaneously relax. Working with a koan can have an equivalent effect on our thinking minds - sooner or later, they simply run out of steam, and relax all by themselves. (That's why koans are such an effective approach, particularly for people who aren't able to 'just let go' into Silent Illumination - which I wasn't when I first learnt it!) An equal and opposite mistake We have to be careful, though. Letting go of the thinking mind is not the same as giving up on solving the koan - but that's a tactic that people sometimes try. 'It's just semantics!', 'It's just a game', 'I don't care what the answer is any more', 'Why can't you just tell me?' (I would if I could, but it wouldn't help!) Koan practice only works if we're able to maintain what Zen master Hakuin called Great Doubt, and what my Zen teacher Daizan prefers to call 'wanting to know' - a sense of continuing to press forward toward some kind of resolution, even when the koan has become totally meaningless and we have no idea which way is up any more. If, instead, we give up, then it's easy to fall into the seductive trap of a stagnant kind of quietism, sometimes called 'the ghost cave on the dark side of the mountain' (eep!). We say 'Well, I can't figure it out, so there's no point. Just let it all go. Just sit quietly and don't worry about anything.' That sounds a bit like the instructions for Silent Illumination, but the attitude behind it tends to point instead to what's sometimes called 'subtle dullness' - a condition in which the mind basically shuts down and disengages from what's going on, and the practitioner just sits there with nothing much going on. It feels kinda restful, and it definitely provides an escape from the struggle of wrestling with the koan, so that must be good, right? Wrong. (Sorry.) If over-thinking was the mistake of 'clinging', the ghost cave is the equal and opposite mistake of 'ignoring'. Training ourselves to deal with problems by turning away from them is emphatically not what Zen practice is about - it's actually a kind of 'spiritual bypassing', a way of (mis-)using practice to avoid dealing with the things we don't want to have to face. The trouble is that life is full of things that we don't want to have to deal with, but we have to deal with them nonetheless, and turning away is just putting off (and often compounding) the problem. A more extreme version of this mistake is to give up on practice entirely, throwing out the baby with the bathwater. A version of this actually came up for me recently. For pretty much my whole life, I've admired people who are very focused on doing one thing well, whereas I've always been prone to doing too many things at once, spreading myself too thinly. On a good day, I can recognise that I love the richness of having multiple interests, but on a bad day I'm convinced that all of my problems stem from a lack of commitment. A pretty big theme over the last ten or fifteen years of my life has been gradually streamlining my commitments and trying to bring more quality time to fewer things. Then, just recently, during a particularly disastrous meditation retreat (that's a story for another time, and probably not one that I'll publish on this blog!), I realised that I've now achieved what I set out to do - I really have pretty much pared things down to the minimum set of activities needed to pursue the most important things in my life. And yet I was still surrounded by problems and sources of unsatisfactoriness, and having a generally miserable time. My grand strategy to 'sort my life out' had, basically, failed - not because it was a bad strategy, but because life isn't like that. No matter what you do, there will be sources of dissatisfaction in all directions. In short, this was a very visceral experience of the Buddha's First Noble Truth - in life, we suffer. The next thought that occurred to me was 'So what's the point of it all? Why not just give it all up and eat cookies all day? At least I enjoy that!' In other words, I'd overshot the mark - I'd gone from clinging to an unachievable ideal about how wonderful life would be if only I could sort out x, y and z to the opposite extreme, trying to retreat into a cocoon of pleasure where I could ignore the rest of the world. Luckily, the habit of practice is pretty ingrained at this point, so I didn't give up entirely (otherwise I'd never finish this set of articles!). And, actually, once I got past the frustration that all my efforts had not resulted in a perfect life, the arguments for keeping up with all the various facets of my work and practice became obvious. Evidently on some level I'd been holding onto the hope that all those activities would sooner or later 'fix everything' - but I also do them because I enjoy them, and I wouldn't actually want to give them all up. On the other hand, it's also now manifestly clear that, while giving up eating cookies will help my waistline, it isn't going to eliminate my existential suffering, and so it probably isn't the end of the world if I continue to eat them from time to time. I usually don't talk about what's going on in my practice right now because it's a risky thing to do - I'm never quite sure whether there's another massive revelation just around the corner, or whether I'm even getting my point across when I'm attempting to articulate something that's very much a work in progress as opposed to something that I can look back on with plenty of perspective. But maybe there's some value in sharing something a little 'rawer' than usual - well, you can be the judge of that! So what's the take-home message here? The koan presents us with an impossible choice: we can't cling to our analytical minds, but we can't ignore them either. So what the heck are we supposed to do? We can see similar 'impossible choices' in many of the great paradoxes of spirituality - the apparent contradiction between the relative and the absolute, or Shunryu Suzuki's beautiful statement regarding the simultaneous need for self-cultivation and self-acceptance: 'Each of you is perfect the way you are... and you can use a little improvement.' The simple answer to these kinds of problems is to recognise that context matters. Sometimes, we absolutely need self-acceptance. (I'm blind in one eye - no amount of yelling at myself to 'do better' is going to give me depth perception.) Sometimes, we absolutely need self-cultivation. (I'm taking on a new project at work and I don't know anything about it yet. My colleagues will not be impressed with my Zen 'don't know mind' - I'd better do some reading!) The drawback with that 'simple' answer is that we've just created another problem. OK, in what situations do we need self-cultivation, and in what situations do we need self-acceptance? How can we tell? The more we dig into questions like this, the harder it gets to find a nice answer that's easily articulated. Every system, every strategy seems to have its blind spots. Every situation is different, and it's impossible to foresee all of the consequences of whatever actions we take. The worst experience of our lives may turn out to be a turning point that ultimately transforms us for the better - but there's no guarantee that this will be true, and deliberately trying to have awful things happen to us isn't a good plan either! Fundamentally, life is mysterious. As Kierkegaard said, 'Life can only be understood by looking backward; but it must be lived looking forward.' Or as Daizan puts it, 'None of us actually know anything about anything... and yet we still live and love.' Ultimately, all we can do in any given situation is the best we can at that moment, on the basis of our experiences and skills up to that point, and the intentions that we've cultivated within ourselves to act in the world in a way that seems right to us - whatever that means in practice. And even then we won't know if we're getting it right! Another way to put this is using an image that occurred to me one night on the difficult meditation retreat that I mentioned earlier. In the moment, I was pretty convinced that the situation was totally unworkable - I couldn't see a way to get through it, given all of the challenges that were facing me at that point. (I couldn't even get to sleep, to make the time pass quicker!) But then I realised that I was getting through it, moment by moment. OK, time felt like it was passing like treacle, but even so each moment of experience was one moment closer to the end of the ordeal. It wasn't fun, it wasn't glamorous, I wasn't feeling how I thought a big fancy experienced meditator like myself should be feeling - but, nevertheless, I was getting through it. The image that came to mind was the difference between a maze and a labyrinth. Sometimes these terms are used interchangeably (as I was reminded when I was trying to find an image of a labyrinth and all I got was mazes!), but actually there's a difference. A maze has wrong turnings and dead ends. You can get lost in a maze. You can wander a long time without getting any closer to your destination. The question posed in the koan at the top of this article evokes a maze - you can turn left or right, but they're both wrong! A labyrinth, on the other hand, is actually just one long twisty path. It has one destination (usually the centre), and although the path itself twists and turns, there are no 'wrong choices' - you can't get lost in a labyrinth, and even when it looks like you're walking in exactly the wrong direction, your footsteps are actually carrying you closer to the destination with complete certainty. My sense now is that life is a labyrinth. We know where we're going to end up - all that arises passes away, and all beings who are born will die sooner or later. The path we take through life is pretty twisty and turny, and sometimes it looks like we're going in a totally different direction than we'd intended. And yet, with each passing moment, we advance one step further. From an absolute perspective, there are no wrong choices, just choices. There's just life, flowing through us moment by moment. We do our best to make good choices, and sometimes the consequences line up with what we'd hoped for, and sometimes they don't. If we really understand this, we can perhaps at least let go of some of the stress, angst and guilt that goes into second-guessing our every move - we can realise that we're doing the best we can with imperfect information, and that's all anyone is ever doing. We can, perhaps, stop holding ourselves back from the moment at hand until we're able to calculate all the possible outcomes of our choices in order to choose the absolute best - and simply get on with it, doing whatever seems to need to be done, bringing as much presence, attention and care as we're able to muster right now. Little by little, moment by moment, we discover what lies ahead on the winding, labyrinthine path of our lives.

May your journey go well. |

SEARCHAuthorMatt teaches early Buddhist and Zen meditation practices for the benefit of all. May you be happy! Archives

June 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed