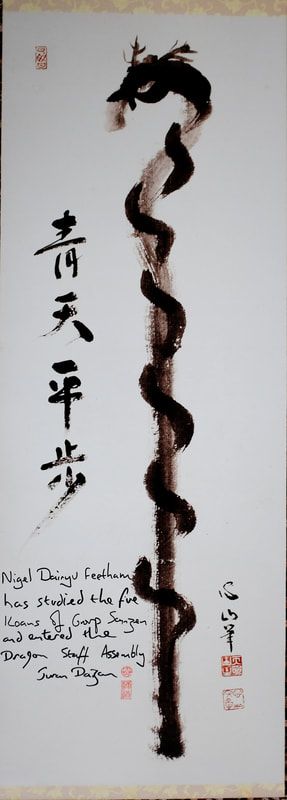

The winding road of Zen practiceThe image above is a painting of a staff transforming into a dragon, symbolising Zen awakening. Copies of this scroll have historically been given to Zen students who have met a certain bar in their practice. Within Zenways, my Zen sangha, it was the practice at one point to give a copy of this scroll to students who'd studied all five Group Sanzen koans, as you can see from Daizan's inscription above. The image is taken from Nigel Feetham's website, used without permission.

This week we're looking at case 44 in the Gateless Barrier, simply titled 'A Staff'. As usual, on the face of it, it doesn't seem to make much sense - but once we get into the symbolism involved, it'll hopefully become a bit clearer.

Giving you a staff: formlessness to form Zen teachers often have a staff, which represents their role as a teacher. More generally, the staff represents a method, a form of practice. When we are first drawn to the spiritual life, we begin in a state of 'formlessness'. Perhaps we have an aspiration - to be a better person, to achieve enlightenment, to find peace of mind - but unless we have a practice of some sort - something to do - it's difficult to make that aspiration a reality in our lives. Traditions like Zen and early Buddhism offer us a whole variety of methods of practice. Perhaps we're drawn to exploring a spiritual question through koan study, or perhaps the holistic nature of the Eightfold Path appeals to us as a way of life. One way or another, in the early stages, we very much need some kind of 'form' - a practice or set of practices that we can undertake consistently over a period of time (weeks, months, years). Here, a teacher is very helpful. Of course we can concoct our own spiritual path, either from a single tradition or by blending together techniques from a variety of sources (just like I tried to 'teach myself' to play the guitar when I was a teenager!). But it tends to be much easier and more effective to find a teacher that we're willing to work with - in an ideal world, a teacher has already travelled at least some of the path that interests you, and they can help to save you time by pointing out the common pitfalls and correcting mistakes that are easily seen from the 'outside' but more difficult to spot from the 'inside'. Different teachers take different approaches to providing 'form' for the student. Some teachers develop systems and curriculums which encapsulate what that teacher understands the Dhamma to be. Other teachers prefer to guide students on a more individual basis, trying to find the forms which best suit that individual. I tend more toward the latter, although I had a bit of a stab at system-building here - in a nutshell, I generally recommend that people have a practice that combines concentration, insight, heart-opening and energetic cultivation, with a strong ethical foundation. In any case, when it's working well, the teacher will be supporting the student to develop in a way that's working well for them. That's the first part of the koan here - 'If you have a staff, I will give you a staff.' At least the way I understand Dhamma teaching, it isn't my job to tell you how to live your life; rather, it's my job to help you work within the life you already have and do my best to support and accelerate your progress. As such, I'm not looking at you as a person with no staff who needs to be given my staff (which is, of course, the best of all staffs) - rather, I recognise that you already have a staff, and I'm just supplementing what you already have, to the best of my limited ability. Taking your staff away: form to formlessness In the fullness of time, practice begins to mature. In the early stages, you're learning 'how to' - you're getting the basic instructions for a practice and figuring out how to do it in the most basic sense. As we continue to practise over the months and years, however, a transition takes place. At the beginning, we're working with a technique that someone else has given us. In the fullness of time, however, the practice becomes our own. We develop our own relationship to it, our own sense of how the practice works, and how best to engage with it in this moment, with this particular set of conditions. This transition reflects a process of integration - a blurring of the boundaries between 'this technique' and 'me'. Gradually, the separation between the two disappears. My daily Silent Illumination practice is no longer a fancy Zen meditation performed with much ceremony and specialness; it's simply how I start each day, sitting quietly and watching my experience. At times I'll find myself sitting in the same way on train or coach journeys, simply observing. There's no real distinction between 'formal practice' and 'informal practice' - resting in awareness has simply become one expression of my life, which emerges when the conditions are right. (Perhaps that sounds a bit grandiose! I don't mean to suggest that I'm incredibly advanced or have an amazing practice, or anything like that. I'm just trying to highlight the way in which my relationship to my practice has changed over the years.) In some ways, this period of practice can even bring up a bit of sadness. The novelty has very much worn off! Indeed, there can be a sense that practice 'used to be more interesting' - particularly when things are first taking off, it's quite common to have lots of deep insights, and to start to feel a bit special as a result. 'Look at me!', you might think. 'All these other suckers don't understand anything, but I know what the Buddha was getting at, I understand all these Zen texts!' The technical term for this stage of practice is 'the stink of Zen'. My teacher's teacher, Shinzan Roshi, would sometimes hold his nose and say 'stinky, stinky!' if people were getting a bit too impressed with themselves. It's an exciting period, but it's also an immature one, and a responsible teacher will typically do their best to bring the student's feet back down to the ground. And that's what the second part of the koan indicates - 'If you have no staff, I will take your staff away'. Early on, a very intense fascination with and attraction to the forms of practice can be very helpful - but past a certain point it simply becomes another kind of attachment, another ego support to make ourselves feel special because of all of our wonderful insights. In the long run, the spiritual path is all about letting go - and that includes letting go of the story of what a great meditator we are. And thus we return again to formlessness - letting go of our attachment to specific techniques, allowing our practice to integrate itself so completely that there's no distinction between 'practising' and 'not practising'. This is a long and difficult journey, and perhaps one that takes a whole lifetime to 'complete' - but it's also a rewarding one. Along the way, we learn the true value of these practices as they manifest in our own lives, not as they're portrayed in ancient texts from other cultures around the world. Gradually, we return to formlessness; this second formlessness is both fundamentally different to, and fundamentally the same as, the first formlessness at the beginning of our practice. As T.S. Eliot put it: We shall not cease from exploration And the end of all our exploring Will be to arrive where we started And know the place for the first time. Through the unknown, remembered gate When the last of earth left to discover Is that which was the beginning; At the source of the longest river The voice of the hidden waterfall And the children in the apple-tree Not known, because not looked for But heard, half-heard, in the stillness Between two waves of the sea. Or, in the words of the great Zen master Bruce Lee: Before I learned the art, a punch was just a punch, and a kick, just a kick. After I learned the art, a punch was no longer a punch, a kick, no longer a kick. Now that I understand the art, a punch is just a punch and a kick is just a kick. Where are you on this journey? Do you have a staff, and if so, do you have the support of a teacher who can ensure that your staff is in the best shape it can be? Or is it time to let go of your staff - and if so, do you have a teacher on hand to point out when you're reflexively grasping at the familiar, comfortable staff that's brought you so far, and to prise it gently out of your grasp?

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

SEARCHAuthorMatt teaches early Buddhist and Zen meditation practices for the benefit of all. May you be happy! Archives

June 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed