The Eightfold Path, part 1

This article is the first in an eight-part series taking a look at the famous Eightfold Path, a teaching found at the core of early Buddhism.

As the name suggests, the path consists of eight factors. Note, however, that it's an 'eightfold' path rather than an 'eight-step' path - the eight factors, or 'folds', are intended to be practised together, rather than one after the other. We can even see this in the language used for each of the eight factors: samma ditthi ('right view'), samma sankappa ('right intention') and so on. The 'sam-' prefix is the same one used in samadhi, which means something like 'bringing together' or unifying. So these eight 'folds' are intended to be brought together and practised as eight aspects of a single path, rather than being a series of stages that you pass through and graduate from. Indeed, one of the criticisms of the modern mindfulness movement is that it essentially extracts two of the eight folds (samma sati, 'right mindfulness', and samma samadhi, 'right concentration') and attempts to offer them without their wider context - particularly including the ethical aspects of the path, which we'll come to in a few weeks' time. Now, personally, I think that modern secular mindfulness can be offered in a way which does include an ethical component, but equally there's a lot to be said for engaging with the whole Eightfold Path - whether you think of yourself as a Buddhist or not. If nothing else, each of these eight factors can be contemplated in the context of your own life, to see what meaning they might hold for you and how you might be able to work them into your meditation practice and your wider day-to-day activities. It's also worth noting that the English word 'right' isn't necessarily the best translation of the Pali word 'samma' - for example, 'right' doesn't have anything like that connotation of 'togetherness' that I mentioned above. It can also come across as judgemental, like 'this is the right thing to do and everyone else is wrong'. For this reason, some teachers today suggest 'wise' or 'appropriate' instead of 'right'. Personally, I don't really like any of these! So I tend just to say 'right', because it's the most common one you'll encounter, and thus hopefully the least confusing for people who don't already know enough about the subject that they don't need this paragraph of explanation! Enough with the preamble - let's jump in to the first of the eight folds, samma ditthi - right view. What is right view? In Digha Nikaya 22, the longer discourse on mindfulness practice, the Buddha defines right view simply as 'Knowing about suffering, the origin of suffering, the cessation of suffering, and the practice that leads to the cessation of suffering.' Astute readers will recognise these as the Four Noble Truths, another central pillar of early Buddhism. (There's a nice self-referential detail here: the fourth of the Four Noble Truths is the path of practice, which is typically equated with the Eightfold Path - and the first aspect of the Eightfold Path is right view, which is here equated with the Four Noble Truths. I like that kind of stuff.) Now, I've written before about the Four Noble Truths, so go and check out that article if you're totally new to the idea. In a nutshell, though, the Four Noble Truths is a kind of tweetable version of the whole Buddhist path.

(OK, that's too many characters for a single tweet. I'm not really a Twitter person.) In a nutshell, then, the Buddhist path is about studying our first-person subjective experience and learning to understand its cause and effect - how our experience comes to be, how our suffering arises, and how that suffering can cease. The good news is that other people have been through the same thing, and mapped out a path for us to follow to get through it ourselves. A more detailed elaboration of right view There's actually a whole discourse on right view, Majjhima Nikaya 9, which unpacks right view in more detail, and in particular delves more into the cause-and-effect aspect I mentioned above. The discourse starts with Sariputta, one of the Buddha's chief disciples, giving a teaching on right view. He starts by saying that 'right view' is a matter of understanding 'the unskilful and its root, and the skilful and its root'. 'Skilful' is one of those Buddhist jargon words that means anything which is helpful in our practice - so having a daily meditation practice would be regarded as skilful, while setting fire to people's houses for fun would fall into the 'unskilful' category. (Why? We'll talk more about that in a few weeks, when we get to the fourth factor of the Eightfold Path, 'right action'!) Sariputta goes on to say that the 'unskilful' is 'killing living creatures, stealing and sexual misconduct; speech that's false, divisive, harsh or nonsensical; and covetousness, ill will and wrong view.' All of these factors develop out of the 'root' of unskilful behaviour: 'greed, hatred and delusion'. Similarly, 'skilful' behaviour is basically avoiding unskilful behaviour, and traces back to the root of 'contentment, good will and right view'. You'll note that the roots of skilful behaviour are the opposite of the roots of unskilful behaviour - so 'right view' is here being defined as the opposite of 'delusion'. The monks then ask Sariputta to define right view in another way, and so he offers a few alternatives. One is simply the Four Noble Truths that we've already seen. Another is an examination of 'fuel' - that is, the things that give rise to greed, hatred and delusion; Sariputta says that when these are fully understood, the roots of the unskilful can be abandoned, and one's suffering left behind. Finally, Sariputta defines right view in terms of a thorough understanding of Dependent Origination. Again, I've written previously about Dependent Origination, so check out that article if you're new to it. The simplest form of Dependent Origination is the observation that every aspect of our experience - every object we encounter, every thought or feeling we have, etc. - arises dependent on other things. Nothing whatsoever within our experience is outside the web of causality - absolutely everything is dependent on other things, and has no existence independent of that. I recently heard the meditation teacher Michael Taft comment that this dependently originated nature of all things can be compared to the words in a dictionary. When you look up a word, you find that it's defined in terms of other words. If you look up those words, they're also defined in terms of other words - maybe even including the first word you started with. There's no 'ultimate word' that exists independently of all the others and from which all the others derive their essential meaning. And yet despite the contingent, unstable, mutually dependent nature of the words in a language, the words are still really useful! It isn't that they don't exist just because they depend on other words. The point is rather that there's no particular 'special word' that is the source of everything else. And, in just the same way, no matter what aspect of our phenomenal experience we examine - sights, sounds, thoughts, feelings, intentions, impulses, memories and so forth - all we ever find is phenomena that depend on other phenomena. In particular, it can be very helpful to apply this examination to ourselves. Who are you, really? For most of us, it feels like there's a definable 'me' here, perhaps sitting behind the eyeballs pulling the levers that move the arms and legs around. But can you actually find such a thing in your experience? Can you find anything truly independent, anything that's 'in charge' of everything else? Right view as emptiness Perhaps the fullest expression of this approach to right view that's found in the early discourses is in Samyutta Nikaya 12.15, where Kaccanagotta asks the Buddha about right view, and the Buddha says 'This world, Kaccana, for the most part depends upon a duality — upon the notion of existence and the notion of nonexistence. But for one who sees the origin of the world as it really is with correct wisdom, there is no notion of nonexistence in regard to the world. And for one who sees the cessation of the world as it really is with correct wisdom, there is no notion of existence in regard to the world.' The language is tricky, but the Buddha is making a version of the 'dictionary' point above. We tend to believe that things either exist in a definite way or don't exist at all, but actually what we find is more like a web of things all dependent on each other, neither existing 100% in their own right, nor not existing at all. As time went on, this idea was developed much further, and became more commonly known as 'emptiness'. Again, I've written previously about emptiness (e.g. here), so I won't do a deep dive now. For today, it's enough to say that a key aspect of right view is to understand this web of interconnected dependency very deeply. Much of our confusion and suffering comes from seeing the world in fixed terms, hanging on to a frozen idea of a person or situation and then being surprised and dismayed when the living, breathing, dynamic reality moves in another direction. A big part of practice is relaxing our fixed views of what's going on, and correspondingly suffering less. The key point about all of this is that right view, like each of the other aspects of the Eightfold Path, is something to be practised. It isn't enough to think about it and come up with a logical argument in favour of or against the ideas of emptiness, dependent origination and the cause-and-effect relationships of our suffering. Rather, we are to see and experience these things for ourselves, directly - like biting into a piece of mango rather than reading a scholarly essay about the nature of mangoes. Right view as the first of the eight 'folds' Earlier I commented that the eight aspects of the path are intended to be practised together rather than sequentially. Nevertheless, we can also look at them in sequence - each one provides support for the one that follows it, and in particular it makes sense to start with right view. If we don't know where we're going, how will we know if we're getting any closer? Having a sense of the over-arching view of the Buddhist project helps us to orient ourselves within the sometimes confusing multitude of practices, traditions and teachers. Fundamentally, Buddhism is concerned with the alleviation of suffering - enabling us and those around us to live happier, more fulfilled lives. If your practice is making you hostile, judgemental and uptight, something has gone a little off track somewhere along the way. But if you find more gratitude, love and joy in your life, especially in relation to the simplest things, you're moving in the right direction. May you be happy and free from suffering.

0 Comments

Stillness and motion in Zen practice

This week we're looking at case 36 in the Gateless Barrier, a classic collection of Zen stories, or koans, compiled in the early 13th century. Once again we find ourselves dealing with Zen master Wuzu, who we met for the first time last week in case 35. In that case, he asked a monk a question about a well-known Chinese folk tale. This week, he seems to have more practical matters on his mind.

So - when you're out and about, and you meet someone who is enlightened, what should you do? Master Wuzu seems to be saying that we shouldn't speak to such a person, but we shouldn't remain quiet either. So what the heck are we supposed to do? Encountering people who have attained the Way Before we go further, there's an interesting point here. The question presupposes that we have met someone who has 'attained the Way' - in other words, someone who has realised the awakening of Zen for themselves. But how are we supposed to know whether someone else is enlightened or not? Tellingly, Wuzu's question begins 'On the road' - in other words, outside the confines of the monastery, with its rigid hierarchy and small population, where everyone knows who the Roshi is, everyone's heard the gossip about how highly attained the head monk or nun is or isn't, and so on. When we're working within a community that we know very well, we automatically have a fairly clear sense of the pecking order - we know who should be treated with respect (and whether or not they've earnt it, at least in our eyes!). But once you step out of that environment, the situation is much more ambiguous. A random person walking down the street might be a Buddha in disguise - or a criminal mastermind. How can you tell? What are the signs of someone who is fully enlightened, anyway? Different traditions seem to hold different ideals - and the highly experienced teachers I respect all seem pretty different to one another. My Zen teacher Daizan, my early Buddhist teacher Leigh Brasington, Stephen Batchelor and Brad Warner are all pretty different to each other. Does that mean only one of them has 'got it'? Exploring this question can show us a lot about what we're hoping to get out of our practice, which in turn can clarify and strengthen our intention, helping us to move in that direction (assuming we still want to after we realise why we've been practising up to this point!). Another way this question is important is that it exposes the way we can treat people differently depending on our relationship to them. It's quite natural (rooted in our biology) to treat our family with greater kindness and attention than total strangers, for example. But a big part of Zen practice is about questioning the validity of the dualities we set up - in this case, between 'us' and 'them'. (My teacher Leigh Brasington likes to ask 'How big is your "us"?') In this case, Zen master Wuzu asks us how we might behave towards someone we regard as enlightened - but if I find myself thinking 'Oh, well, I should clearly be very respectful and listen carefully to what such a person would have to say,' well, does that mean that I don't feel the need to be respectful or attentive toward someone who I don't regard as enlightened? Do I have a sense of a kind of 'spiritual elite' who are worth my time and attention, as compared to a vast mass of ignorant plebs who I'm free to ignore because they haven't 'got it'? Hmm. This problem can also show up in a more insidious form as we get more into Buddhist practice, particularly if we have some significant shifts or insights. It's very easy to think 'Ahh, now I get it - not like those losers over there who talk a good game but don't know the real stuff!' When someone is a bit too impressed with their own level of insight, it's sometimes said that they 'stink of Zen' - Daizan's teacher Shinzan Roshi would sometimes hold his nose and say 'Stinky, stinky!' This is a very sneaky problem indeed, because we don't want to devalue the genuine power of insight - but equally it's very easy to start thinking of yourself as special if you've had a breakthrough. (At the end of a retreat, if there's been a bit of this kind of thing going on, Daizan will sometimes get us to turn to the person next to us and say 'Hi, I'm Matt, and I'm a bit special...') If you do fall into this trap, it isn't the end of the world, but at some point you'll come back down to earth, perhaps with a bit of a bump. Finding out that you're not so special after all is a hard lesson to learn, but learn it you must. (Went a bit Yoda at the end there, not sure what that's about.) Not speech, not silence Leaving aside for a moment the thorny problem of how to recognise someone who is enlightened, we also have Wuzu's other conundrum to deal with. He says 'You do not face them with speech, you do not face them with silence. So tell me, how do you face them?' That's a bit like saying 'You can't turn left, you can't turn right, so which way are you going to turn?' I've mentioned a few times before that Zen master Wumen, who compiled the collection of koans that this story comes from, provides both a prose and a verse comment for each case. Usually I don't include those, in general because they're just as difficult as the main case and I only have so much time on a Wednesday night to render all this stuff into an accessible enough form that we can practise with it. This time, however, Wumen takes the unusual step of giving us a direct answer to the case in his verse comment. On the road, meeting people who've attained the Way, You do not face them with speech or silence: Punch them right in the jaw; If they understand directly, they understand. As usual, we're not meant to take this entirely literally, fun as that might be. (One of my martial arts teachers used to say 'The problem with you guys is that you take things too literally', to which I was always tempted to suggest that he could just say what he meant instead... but he was a pretty scary dude, so needless to say I never said that to him.) Wuzu is cautioning us against two possible errors when approaching a situation (any situation, actually, not just an encounter with an enlightened master). Koans are often critical of an overly intellectual approach to Zen - we commonly see scholars defeated by uneducated tea sellers and the like. 'Speech' here could be seen to represent an academically wise, philosophically erudite approach, perhaps based on some kind of well-intentioned principles - in other words, an attempt to 'figure out' what to do in advance, using the powerful tool of the intellect to reason our way to success in every circumstance. Alternatively, we can simply withdraw, and hope to avoid error by not committing to any definite action, remaining silent, perhaps hanging out in the peaceful stillness of our meditation practice where we don't have to deal with the messiness of other people 'out there'. The alternative is what we might call dynamic action - a response which fits itself to the situation like a hand fits a glove (or like Wumen's fist fits my jaw). We engage, but not in a predetermined way, simply acting out a script written long ago. Rather, the focus of our practice is on bringing ourselves as fully as possible into the here and now, and trusting that an appropriate response will arise within us to meet the needs of the moment. (What is 'an appropriate response'? That's another koan in its own right - I'll leave that one as an exercise to the reader!) Form is emptiness, emptiness is form One of the most famous lines in all the Buddhist canon is 'Form is emptiness, emptiness is form'. This line, from the Heart Sutra, can be viewed as a very concise map of Zen practice. Most of us come to practice seeing the world in a certain way - a world of separate, disconnected things, like a series of billiard balls rolling across a table crashing into each other. Zen practice invites us to find a different way of seeing things which is based not on separation but rather on wholeness. That sense of wholeness can be reached through a variety of means, but very commonly through developing an orientation towards stillness, silence, nothingness, emptiness. When we're caught up in the things of the world (and in particular the thoughts that represent our discriminating mind's activity of chopping up the world into separate, individually labelled pieces), it's very difficult to see the wholeness - so we incline toward the gaps between the things, rather than the things themselves - the space in the room, rather than the furniture. When we find our way to emptiness, it's often a tremendous relief. The mind is able to let go of all its usual worries and obsessions, at least for a moment. Finally, we can rest - but rather than falling asleep, we're wide awake, perhaps more fully awake than we've ever been before. It's a lovely experience, and it's quite natural to want to hang out there as much as possible. However, as another Zen saying puts it, 'heaven is the most dangerous place'. If we become too fixated on the peaceful stillness, we become intolerant of any disturbance, allergic to the world and the day-to-day dealings of our lives, seeking only to get back to that peaceful place as soon as possible. So the next step of the practice is to recognise that emptiness is form. It turns out that the peaceful stillness is not so much an end in itself as a very helpful doorway that leads us to that sense of wholeness. Once we're more familiar with it, we can start to find it everywhere - even in the particular things of the world. Ultimately, all of our experience has the same underlying nature - the nature of mind - and if we can recognise that in any given moment then we're right back in touch with that sense of wholeness. Trying to push away form to get to emptiness (or trying to suppress thoughts or sounds to get to inner and outer silence) is fundamentally to misapprehend what's going on, setting up a false duality between stillness (good) and movement (bad) rather than recognising them to be two sides of the same coin. Instead, wholeness can become a kind of background texture throughout all of our experience, no matter what's going on. Acting effectively in the world The Zen tradition thus places a strong emphasis on continuous practice, which flows between stillness and movement and back again. We sit in meditation (zazen), of course, but we also walk, work and speak with the same attitude of mindful presence that we bring to our sitting meditation. (This 'meditation in action' is sometimes called 'do-zen'.) This is also where Zen's energy practices fit into the picture. We can see sitting meditation as a fundamentally subtractive activity - resting in stillness, letting go moment by moment, gradually becoming less in the process. By comparison, energy practices such as qigong can be seen as fundamentally additive in nature - generating and circulating energy, promoting health, refining the functioning of the body to live longer, becoming more in the process. I've written several articles on energy practices, so check those out if this is a side of Zen practice that you haven't encountered before. The bottom line is that we want to get to a place where our well-being is not dependent on the conditions of the moment, where we can see the wholeness that unites all experiences even in the midst of dealing with the particulars of a live situation in the moment. Daizan likes to say that we need both eyes open - the eye that sees emptiness and the eye that sees form. If we're fixated on one at the expense of the other, we become a 'board-carrying fellow' in the Blue Cliff Record (another famous koan collection) - like someone carrying a plank on their right shoulder who can thus only see what's to their left. While it's definitely valuable to focus on silence, stillness and emptiness in the early stages of the practice in order to break through to a clear sense of this new way of seeing things, in the long run it's all about integration. We don't need to set up a competition between form and emptiness, relative and absolute, enlightened and non-enlightened, and then try to make sure we're always on the winning team. So what's this place of integration like? Unfortunately, it can't be boiled down to a simple strategy ('just do this, this and this in every situation and you'll be fine') - 'speech' is not a viable option here. But doing nothing ('silence') isn't going to work for us either. Ultimately, we have to find out for ourselves, moment by moment, as the activity of our lives plays out. In the right circumstances, maybe that even looks like a punch to the jaw. Let's find out! Half of you is in other people

This week's koan, taken as usual from the Gateless Barrier, is case 35, called 'A woman's split soul' in the Thomas Cleary translation. This is one of those koans that needs a certain amount of cultural context before it can even begin to make sense, so we'll start there.

The story of the woman's split soul The koan is actually a reference to a traditional Chinese story which would have been well known at the time the koan was composed - the sparse text we're given was evidently enough for readers of the era to pick up the reference, in just the same way that most modern readers will know what's meant if I were to say 'use the Force, Luke!' with no further explanation. (Maybe I should substitute 'Rey' for the young'uns among you...) Anyway, rather than attempt to write my own telling of the story (which, although fun, I don't really have time for this morning), here's a version of the story that I found on the Zen Center of Syracuse website. (Note that the story uses the Japanese version of the characters' names, which is common practice in Zen lineages tracing back to Japan. In the original version of the story, of course, they would have Chinese names.) There was once an old man named Chokan, who had lost his first daughter. As you might imagine, he was very attached to his second daughter. Seijo was her name; Jo means young woman. Seijo was very beautiful, and so was her cousin, a boy named Ochu. The two of them were so cute together. The family would watch the two children playing and say, "Ah, what a great couple they make. How adorable." Chokan often said, "The two of you are so perfect together." Well, they grew older, and indeed they felt that way about each other: "You are right for me. You are my great love." But then, to their dismay, Chokan told his daughter that he had chosen a husband for her. It was not Ochu! We can't imagine that here, but this was a very common occurrence back then, and even not so long ago. Now, too, in some cultures this kind of arranged marriage is quite common. So what happened to this young loving pair? They couldn't bear it. Ochu couldn't stay and see his beloved married off to someone she didn't love. He got into a boat and began making his way up the Yangtze River. Then he noticed someone running along the shore, calling after him. He peered into the darkness-who could it be? It was Seijo! She got into the boat, and they went off together. Years passed. They had a family together. Now the mother of two children, Seijo began feeling deep regret for having run away from her father. Knowing what it's like to love a child, she could imagine his anguish. She said to Ochu, "I long to go back to my native village and see my father and beg his forgiveness." And he replied, "I, too, feel that way. Let us go." So they got into a boat again and went back down the river. When they reached the village, Seijo stayed in the boat while Ochu went to her father. Ochu bowed low and begged for forgiveness for having run off with Seijo. The old man listened with a look of incredulity on his face. "What? Who are you talking about?" Ochu said, "Your daughter, Seijo. She's in the boat." Her father replied, "No, she's not. She's lying in bed. She's been sick all these years, and we haven't known what's wrong; she's been lying there like an empty husk. She hasn't spoken since you left." "But she followed me," Ochu said. "We've been living in another country. We're married, and have two children, and she's in great health. She's here now to ask for your forgiveness." Ochu went to the boat and asked Seijo to come to the house. Meanwhile, Chokan went to tell that sick daughter of his about all this. Still not speaking, she got up out of bed and walked out of the house. Seijo coming from the boat, Seijo coming from the bed, now One. The shocked father said to his daughter, "Ever since Ochu left, you have been lying lifeless, as though your soul had fled." Seijo replied, "I didn't know I was lying sick in bed. When I heard Ochu was going away, I ran after him as if in a dream." So, which was the real Seijo - the one in the bed, or the one in the boat? An allegorical reading of the koan We can approach this koan in a variety of ways. One approach is to treat it as an allegory for a common feature of our psychology - daydreaming. When I was a kid, I loved to imagine all the cool ways my life was going to turn out - all the awesome things I'd be able to do, all the cool people I'd hang out with, all the exciting adventures I'd have. Actually, although I said 'when I was a kid', I still have some of that tendency today - it's pretty common to find myself approaching an activity (let's say learning a new Tai Chi form) with part of my mind busily caught up in imagining how awesome it will be when I'm proficient at it. It's been a hard lesson for me to learn that, while that kind of fantasy is an entertaining way to pass the time, it isn't terribly useful, and it does take up quite a bit of my time and energy if I let it. So a big part of my Zen practice these days is noticing when I'm straying into 'what if?' territory and bringing myself back to what's in front of me. (Or, continuing the Star Wars theme from above and quoting Master Yoda: 'All his life has he looked away... to the future, to the horizon. Never his mind on where he was, hmm? What he was doing.') In this reading, it's fairly clear which is the 'real' me - and it isn't the one with awesome Tai Chi skills, sadly. Taken this way, the koan is a gentle reminder that, no matter how exciting our imaginary life might be, the real one that's right in front of us is the one that really needs attention, and we're perhaps better served working to improve our actual life than imagining a better one but never taking any action to move in that direction. A relational reading of the koan A second way to explore this koan is to take a look at the concept of identity in the context of relationships, where we find another 'split'. Suppose you and I meet. You get to see certain aspects of me, and I get to see certain aspects of you - any other aspects of our personalities that don't come out in the interaction we have remain hidden, so the picture is necessarily incomplete. Finally, we part. I now have an 'idea of you' in my head, and you have an 'idea of me'. In the time we've been together, we've formed opinions about each other - I have some sense of the sort of person you are, the way you speak, the way you dress, the way you behave; and you have the same kind of information about me. The idea of you that I've formed doesn't necessarily bear any relation to what you might regard as 'who you really are'. Hopefully it's close enough to be workable, but every now and again I'll make a mistake because my model of you isn't accurate enough to predict everything about you - so maybe I'll buy you a Christmas present that you hate, or I'll inadvertently say something that upsets you because I didn't realise that topic was a hot button for you. Over time, as I get to know you better, I'll refine my idea of you and (hopefully!) make fewer mistakes, but it'll never be totally accurate, not least because you're constantly changing in small ways as you gain new life experiences, whereas my idea of you only gets updated when we interact, and is basically a frozen snapshot of how you were at a particular point in time (or rather how I thought you were at that point in time!). On a podcast once I heard someone say 'Fully half of yourself is in other people' - it's interesting to reflect that everyone we meet is relating to us through their idea of us rather than our own sense of who we are! In the story, Seijo is seen one way by her father - as a daughter, perhaps with a social obligation to be married according to the father's intentions, as was the way of things in that era in China - and another way by Ochu - as his lover, a life partner, a soul-mate, an independent individual who doesn't have to be beholden to her father's wishes for her. Which is the 'real Seijo' here - the obedient daughter or the independent lover? In the course of a day, we may find ourselves taking on many such roles. For example, right now, I'm a meditation teacher. Earlier, I was a qigong practitioner, and before that a meditator. Later on, I'll be a partner in a relationship. Tomorrow I'll be a colleague, a manager, a managee, a mentor and a researcher, amongst other roles. Sometimes I'm a son, sometimes I'm a godparent, sometimes I'm a friend - and sometimes I'm a thorn in someone's side, although usually not deliberately. In the same way, in the story we see Seijo in a variety of roles - daughter, partner, mother. (It's also noteworthy that when Seijo takes on the role of mother later in the story, it has a profound effect on her, recontextualising the 'daughter' role as she comes to understand her father's perspective better than she previously did.) Each of these roles requires a slightly different set of behaviours, language and so forth. How I speak to my own mother is not how I speak to my goddaughters. Neither mode of address would be appropriate in the workplace. (I've actually seen a senior manager speaking to their staff as if speaking to their children, and it wasn't pretty!) Even when I'm in the role of 'friend', I'm a little different depending on which set of friends I'm with, because we share different interests - Yoda references will land with some of my friends better than others, for example. These roles aren't only about other people's ideas of us - they're also something which exists within ourselves. We don't simply act a certain way in a certain situation because others compel us to do so (although at times it may feel that way!) - we select modes of behaviour which are appropriate to the circumstance, either consciously or unconsciously. It can be worthwhile to spend some time thinking about the many roles that you play in the course of a day, a week, a month or a year. Are some roles more comfortable than others? Do you feel forced into certain roles, or find it difficult to escape others once you've taken them up? Have you found, like Seijo, that taking on a new role (e.g. parent) sometimes changes the way you relate to another role (e.g. child)? Which, if any, is the 'real' you amongst all these roles? Is Seijo daughter, partner, mother, all of the above or none of the above? An existential reading of the koan Most people conclude that none of these roles really fully capture their 'true' self. Roles are more like masks which - ideally - we put on when they're helpful and take off when they're no longer needed. But then what's behind the mask? As we dig into this, we find a third reading of the koan, based on a more fundamental, existential question. We may feel that we have two aspects to ourselves - what we might call 'nature' and 'demeanour', to borrow terminology from a game I used to play at university (ironically, a 'role-playing' game). In the language of the game, the 'demeanour' of a character represented the face that that character chose to show to the world, while their 'nature' represented who they really were, deep down inside. At the time, this struck me as a nice model - I certainly felt like who I was inside wasn't necessarily what other people saw on the surface. Of course, it's not uncommon for teenagers to feel that 'nobody understands me!', but I think some degree of that sense of a split continues into adulthood for many people too. So then we can ask: what exactly is my 'nature'? What sits behind all the masks, at the centre of the web of aspects, personalities, roles and social interactions? What is the deepest, truest part of ourselves - beneath our social identities, beneath even our beliefs about ourselves? Who am I really? In fact, among the classic 'breakthrough' koans (i.e. those which lead to kensho, a first glimpse of awakening in the Zen tradition): we find two which point right to the heart of this exploration: 'Who am I?', and 'What is my true nature?' These are tremendously powerful questions to sit with - if you aren't familiar with how to work with a koan in meditation check out my page on koan study for details. It's well worth the exploration, particularly if you have the opportunity to go deep into the question, such as by going on a retreat like the Breakthrough to Zen retreats offered by Zenways, the sangha I belong to. Going deeply into these questions will change your life forever. One more for the road - a mystical reading of the koan Personally, I've always looked at this koan as being about the emptiness of self, exploring it primarily through the second and third lenses above - although the first perspective is also very helpful as a splash of cold water to the face whenever I'm getting too clever for my own good! A few years ago, though, one of my teachers mentioned another, more mystical, interpretation. Some traditions teach meditation practices which are designed quite literally to separate one's consciousness from one's body, resulting in a kind of out-of-body experience - another type of 'split'. Personally, this is something I don't have much experience of, so it's not a practice that I would ever offer myself. If you're interested, though, here's the link I was given. If you do want to explore this kind of practice, I strongly recommend finding a teacher who is appropriately qualified to guide you! Whichever of these interpretations speaks to you, I hope you get some value from the story of Seijo's split soul. I've found it very fruitful in my own practice; may it be similarly helpful for you. Letting go of resentment: a how-to guideThis week we're going to continue our recent explorations of heart-opening practices by looking at another heart practice which is perhaps less stressed than the four main Brahmaviharas, but which in my view is equally important - forgiveness. Along the way, we'll also dip a toe into the complex, murky waters of karma. So without further ado, let's get into it!

Karma and the cosmic scales of justice Karma (that's the Sanskrit spelling; the Pali, which you'll encounter more in early Buddhist circles, is kamma) is a tricky beast. It's a word that means different things to different people - sometimes multiple different things to the same person, depending on the context. For most people today, the word 'karma' conjures up a sense of a kind of 'divine retribution'. If you do something bad, it'll come back to bite you! A casual YouTube search will reveal many 'instant karma' videos, in which someone does something unkind or unpleasant and then promptly has some kind of accident, injury or humiliation. On a certain level, these can be quite satisfying to watch - one of the great questions that's troubled people throughout the ages is why good things happen to bad people, like being able to do crummy things and get away with it, so it can produce a slightly unsavoury kind of thrill to see someone get their comeuppance. This 'what you do comes back to haunt you' idea of karma is sometimes associated with the idea of rebirth - the view that, rather than living only a single life, we die and are reborn as another person, with another family, another name, another social situation and so on. Most people don't remember their past lives, but some people do claim to, and some meditation teachers offer practices which promise to reveal our past lives to us. In this context, karma is something that can extend across multiple lifetimes - so if something awful happens to you, seemingly for no reason, you're encouraged to see it as negative karma from a previous life coming back to haunt you. This is actually quite a helpful way of looking at things if you're able to do so, because it provides us with a means of understanding why an otherwise seemingly inexplicable disaster has singled us out for torment. Like everything, however, this view of karma also has a dark side. Born disabled? Must be your negative past life karma. Having a difficult time? Well, that's just your karma to work through, I'm not going to help you with it. These sorts of attitudes unfortunately do crop up from time to time. Personally, I tend to regard anything which obstructs the heart's natural compassion in the face of suffering to be a kind of mistake, so any view of karma which says that you should turn your back on someone else's suffering - whatever the reason for it - is not what I would consider very useful. In the time of the historical Buddha, 2,500 years ago, the concept of karma had been effectively weaponised by the priestly (Brahmin) class, who generously offered to intervene in your karma by performing various rituals - for a modest donation, of course. Combined with a world view that suggested that time was basically cyclical rather than linear, and the material world was a prison of suffering into which we were inescapably reborn over and over, you can see why it would be of great benefit to pay the priests to try to ensure a slightly more comfortable experience this time around, to make the best of a bad situation. As he often did, however, the Buddha chose to redefine the term karma within the context of his teachings. In (e.g.) Anguttara Nikaya 6.63, the Buddha says 'Intention, I tell you, is kamma. Intending, one does kamma [literally, 'actions' or 'deeds'] by way of body, speech and intellect.' The point that the Buddha is making here is that our intentional actions have significant consequences. We get good at what we practise - and so, if we regularly practise reacting to difficult situations with anger, we'll find ourselves slipping into anger more easily each time. Conversely, if we practise the cultivation of loving kindness, compassion, appreciative joy or equanimity, those qualities are more likely to be our default responses to situations as they arise. Over time, our intentions have the power to change our character - and so it's important that we're mindful of those intentions, and that they're pointing us in a direction we want to be going, rather than pushing us toward a slippery slope of negativity. The Buddha's view of karma wasn't solely limited to one's personal intentions - elsewhere he does talk about the external consequences of our intentional actions as well. It can be interesting to consider the knock-on effects of our actions - but I already wrote about that quite recently, in the last part of my recent article on equanimity, so check that out if you're interested. For our purposes today, the crucial point is the shift from a focus on karma as an external force of 'cosmic justice' to a focus on one's own subjective experience, and how to work with the contents of one's mind to lead us in a more helpful, constructive direction. Forgiveness, debt and resentment When I run meditation courses for beginners, I'll always include a segment on the importance of forgiveness. Scientific studies suggest that people who practise forgiveness on a regular basis live longer, happier, healthier lives than people who don't - so it ought to be easy to persuade people to give it a go, right? Actually, though, many people find forgiveness very difficult. The major objection I encounter is 'Why should I?' If you've been hurt by someone else, you may well ask why on earth you should forgive them? What have they done to deserve your magnanimity? Maybe nothing! This kind of reaction to forgiveness is quite natural. Going back to the karma discussion, it feels like the cosmic scales of justice are currently slanted away from you. That person did something crappy - they deserve to suffer for what they did, not to be offered your kindness, further imbalancing the scales! We often relate to misdeeds as a kind of 'debt' that has been incurred by the offender - indeed, we talk about prison sentences as 'paying off their debt to society'. From this perspective, giving someone 'free' forgiveness could even seem irrational, like writing off a financial debt rather than trying to recover the money you're owed. From this view, surely forgiveness is tantamount to letting them get away with it! But let's make the same shift of perspective that the Buddha did when talking about karma. Leaving aside the cosmic scales of justice, what is the situation here from your point of view? Something bad happened, and you got hurt, and now - after the event, perhaps even long after - you're continuing to feel some sense of resentment (or anger, or hostility, or...) in relation to what happened. Here's the thing. That resentment is causing pain to you, not to the person who hurt you. The other person might not have any idea that you're still holding on to the pain of what happened - and if they really had it in for you, they might even be pleased to know that their actions continue to cause you pain. It's often said that 'Resentment is like drinking poison and waiting for your enemy to die.' In the words of Tony Stark, not a great plan. So when we talk about 'forgiveness', what we really mean is 'letting go of resentment', as opposed to 'giving someone a free pass and allowing the cosmic scales of justice to remain imbalanced'. When we let go of resentment, we're not saying that what happened was actually OK, or that the other person should be free to do it again - we're not erasing the negative action or its consequences. We're simply letting go of the hot coal that's burning our hand. A second objection that can surface at this point is a feeling that it's somehow useful to continue holding on to the resentment - particularly if we've been feeling that way for a long time. (A kind of emotional sunk cost fallacy, if you will.) We may feel that the resentment helps us to remember not to let something like that happen again. Or it may simply be that it's a little bit embarrassing to admit to ourselves that we've been holding on to something as unhelpful as resentment for a long time. (I've certainly had a great many rather embarrassing insights like that along the way - and no, I'm not going to give you any examples!) What we can do here is to disentangle the two points. On one hand, we have what we might call 'the lesson' - what did we take away from this experience? Perhaps I now know that I never again want to work for a micromanaging bully of a boss, and I'll take active steps to avoid it in the future. Perhaps I know that when someone is very tired, they'll sometimes say extremely hurtful things, and I'm better off just keeping my distance when they're in that kind of mood rather than trying to engage with them. Perhaps it takes a little longer to figure out if there's anything to learn from what happened - in which case this can be an interesting inquiry in its own right, digging into exactly what it is within yourself that reacted so strongly to what happened. (It's worth reflecting on the point that whatever we experience is, in a certain sense, only a reflection of ourselves - our values, beliefs and feelings, being played back at us through the medium of other people. This too can be a profound investigation in its own right!) And on the other hand, we have 'the resentment' - that hot coal of burning pain that we continue to carry. As it turns out, the lesson can be separated from the resentment, and we can (and should!) consciously recognise and absorb the lesson, whilst letting go of the resentment. A practice of forgiveness Supposing you're on board with the 'why' of forgiveness, the next question is 'How do I do it?' Maybe you already have an intuitive sense of this - if so, that's great - but that isn't the case for everyone. The first time one of my students asked me 'How do you forgive someone, then?', I blue-screened. At the time, the question felt a bit like 'How do you know you're in love?' - I don't know, you just do! But since then I've spent some time thinking about the practical mechanisms of forgiveness, and have cobbled together a formal practice with a few discrete steps intended to lead us to a place where we can let go of our resentments. Here's how it goes. Step 1: Bring a situation to mind which triggers some kind of resentment (anger, hostility, ...), and sit with it for a while. I strongly suggest that you start with something easy, and work your way up, rather than jumping straight in to a profoundly tortured relationship with a lifelong nemesis. Like the other heart-opening practices, we want to start where it's easy and then gradually build up - otherwise we risk shutting the heart down completely, like forcibly over-stretching a muscle that then tenses up to protect itself. In particular, please don't try this with something deeply traumatic - if you find yourself experiencing flashbacks, sweating, palpitations etc. then come out of the practice immediately, and I strongly recommend talking to a professional about the situation. Please be kind to yourself. Once you've chosen something, bring it to mind. If you're a visual person, you might like to replay the situation in your mind's eye. Recall as clearly as you can what happened, and notice the reactions that it triggers within you. Spend a few minutes just feeling what's going on within you. (A major barrier to letting go is the instinct to suppress unpleasant feelings. Often, simply allowing ourselves to feel fully is enough to start the process of letting go. It's worth the short-term discomfort of feeling the pain fully in order to get to the long-term benefit of letting it go entirely. Or, as my Zen teacher likes to say, 'Better out than in...') It can also help to try to understand the other person's point of view. Again, it isn't about agreeing with them or approving of what they did, but if you can find a way to understand where they were coming from, it can help. Most people don't set out to do something with the intention of causing evil in the world - generally speaking, everything we do is in the service of making things better somehow, it's just that our ideas of what 'makes things better' can become extremely screwed up, for a whole host of reasons. So if what happened still seems totally inexplicable and cruel to you, it may be worth trying to understand things from another perspective - if you can. If you can't, don't worry about it, just move on to the next step. It's also worth saying that sometimes the person you need to forgive is yourself. In many cases this can be the most important kind of forgiveness - and also the most difficult. Step 2: What is the lesson here? Now take a few minutes to identify what you can learn from the experience. Make sure that you understand what happened - why it had the impact on you that it did. Was one of your personal values or principles violated in some way? Are there other situations that produce the same kind of reaction? What could you do to approach similar situations differently in the future, if they can't be avoided? Don't skimp on this step, particularly if part of your reason for holding onto the pain is because of the lesson wrapped up in it. In this step we're consciously identifying that lesson and taking it on board. Once that's done, the pain has served its purpose, and we can let it go. Step 3: Resolve to let go of the pain. Form the conscious intention to let go of the resentment, and then simply sit with it for a few minutes and see what happens. You may find it helpful to use some phrases to connect with the intention of forgiveness, like the phrases we use in the other Brahmaviharas (e.g. 'may you be happy'). Here are some suggestions:

Sometimes, the pain releases almost immediately, while other times it's a much slower process. In all likelihood, some things won't drop away the first time you practise with them - but that's OK, you can come back to it again. If it's very painful, leave it a few weeks or even months before coming back to it. Don't try to force anything - the heart has its own timetable, so just let the process unfold. There's no rush. May your burden be a little lighter each day. Connecting with our intuition

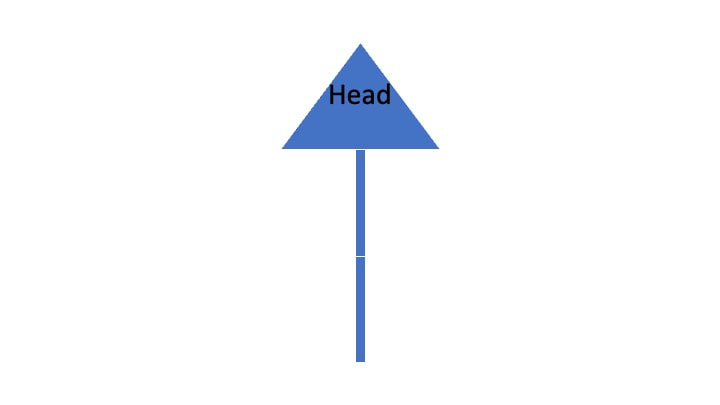

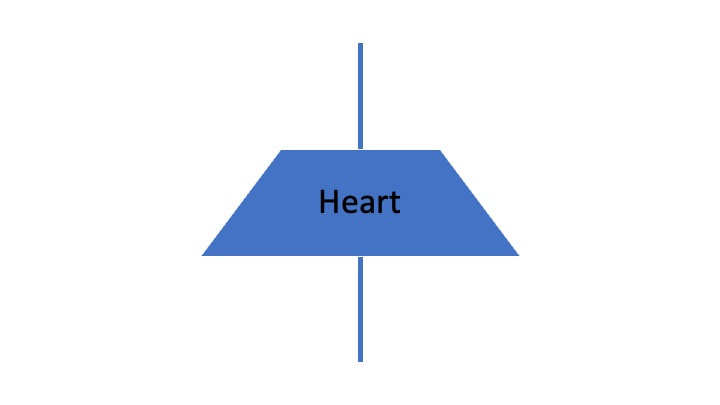

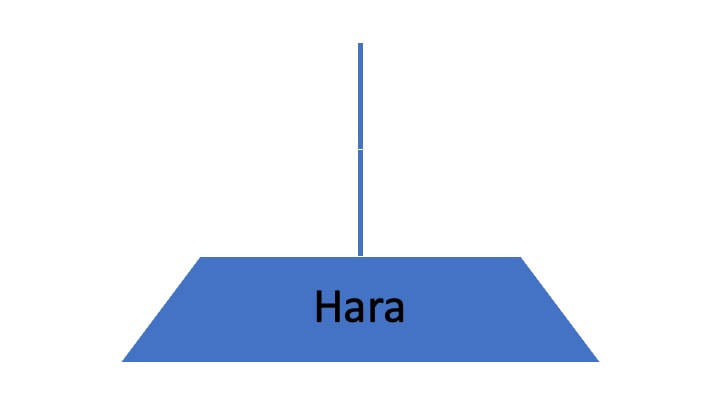

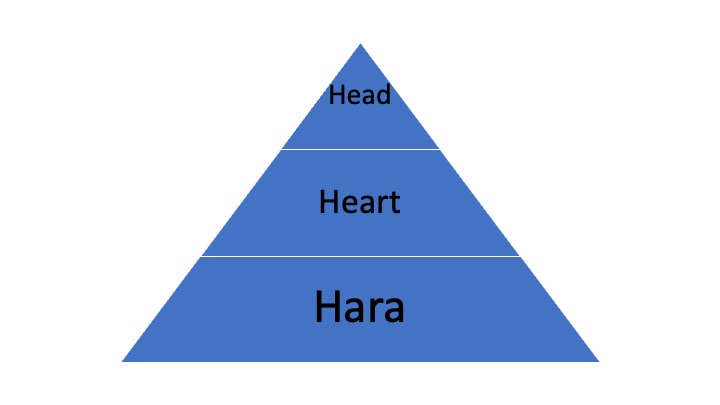

This week we're looking at case 34 in the Gateless Barrier - and if you think it looks a lot like the previous koan, case 33, you'd be right! So this week we'll go in a slightly different direction and look at intuition and the Zen ideal of how a person should be put together. I've even made pictures! So without further ado, let's get into it. Knowledge is not the Way? In the previous case, we saw Zen master Mazu rejecting his earlier saying, 'The very mind itself is Buddha', and instead taking the more contrarian stance 'Not mind, not Buddha'. This week Nanquan cranks the handle even further, telling us not only that 'mind is not Buddha', but furthermore that 'knowledge is not the Way'. I've also seen the second phrase translated as 'wisdom is not the Way', which is even more subversive. If we've been hanging around in Zen circles for a while, we might have got the idea that intellectual, scholarly 'knowledge' is not what Zen is all about - rather, we're supposed to do Zen meditation practices, like koan study and Silent Illumination, in order to have insights and cultivate... wisdom... right? Isn't wisdom the point of all this? Wisdom, after all, is one of the six Mahayana virtues (paramitas, along with generosity, ethical conduct, patience/forbearance/endurance, energy and concentration/focus). And yet here's Nanquan, telling us that even wisdom isn't the way to the Way? So what the heck are we supposed to do, then? Zen's view of the ideal person Before we answer that directly, let's take a moment to look at Zen's idea of a well-put-together person. This is something I've heard my Zen teacher Daizan talk about many times, although it's taken a while to sink in to my thick skull, for reasons that will become apparent as we get into the details! This way of looking at a person divides the body into three sections - head, heart and hara (lower abdomen) - corresponding to the three major energetic centres of the body (upper, middle and lower tanden/dantien). Let's take each one in turn, look at the attributes associated with each section, and see what happens when that aspect of the person is overdeveloped and hence too dominant.

|

SEARCHAuthorMatt teaches early Buddhist and Zen meditation practices for the benefit of all. May you be happy! Archives

June 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed