To arrive where we started and know the place for the first time

This week, we're taking a look at case 33 in the Gateless Barrier. For those of you who like cross-references to other koans, you'll want to compare this one with case 30, and also case 27. (We'll also see a striking similarity next time, with case 34.)

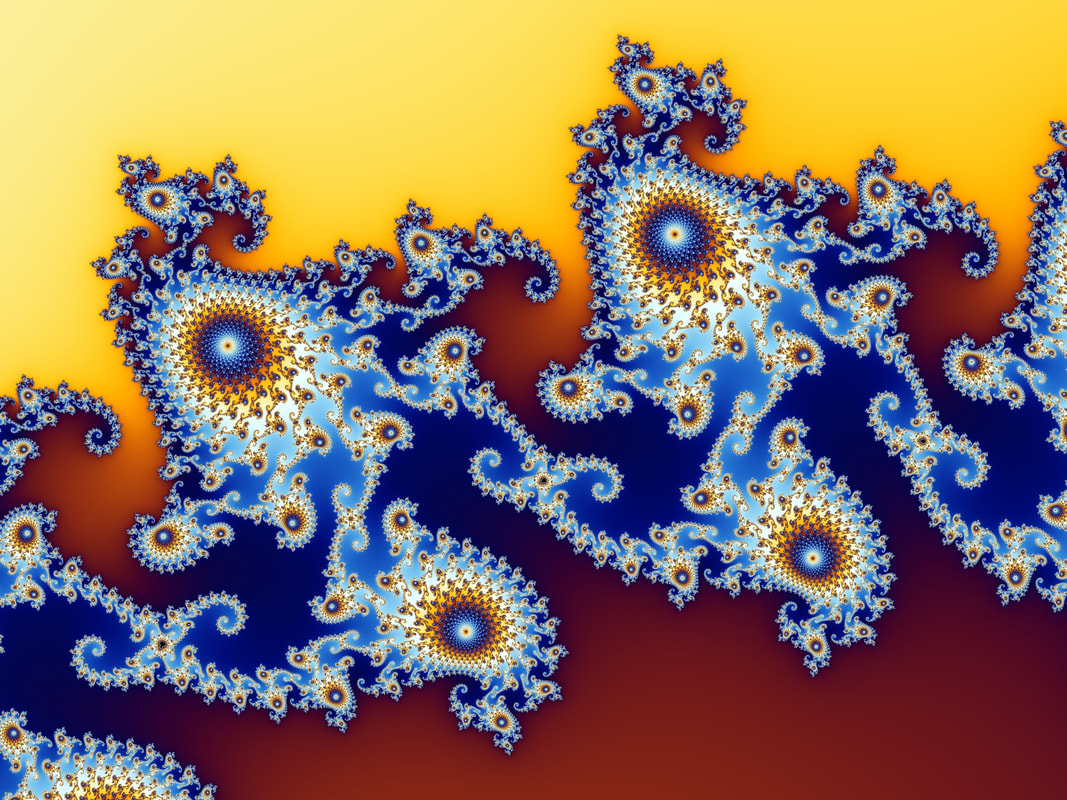

There's quite a lot packed into a pretty terse koan, so without further ado let's jump in and start unpacking it. Necessary context First, we should compare this koan with case 30. In that story, Damei asks the same question ('What is Buddha?'), but there Mazu gives the answer 'The very mind itself is Buddha.' Here, however, Mazu pulls a switcheroo, and says 'Not mind, not Buddha.' What the heck? Are these Zen teachers inconsistent, or what? First, it's worth saying that Zen, and spirituality in general, is positively overflowing with seemingly contradictory statements. This can be for (at least) two reasons. On one level, if a teacher is tailoring the instruction to the audience (as a good teacher should), sometimes the advice will vary wildly. Thai Forest teacher Ajahn Chah once commented that a student is like a person walking blindfolded through a forest, and the teacher is trying to keep them on the narrow forest path. If the student strays too far to the left, the teacher will say 'Go right, go right.' If the student veers off too far to the right, the teacher will say 'Go left, go left.' So sometimes an apparent 'contradiction' can be for a quite mundane reason - it's just what that person needs to hear then and there, as opposed to an absolute commandment to be followed at all times. At a deeper level, my teacher Leigh likes to say that the opposite of a conventional truth is a falsehood, but the opposite of a profound truth is another profound truth. Try to wrap your head around that one! And, actually, that's what's going on in this koan, at least on one level. Damei gains independence in the Dharma The last couple of koans we've looked at (case 31 and case 32) have been developing a bit of a theme of 'independence in the Dharma'. In case 31, an otherwise obedient monk is scolded for following instructions mindlessly rather than exploring for him; in case 32, students who think for themselves are regarded as 'excellent horses', while those who need to be spoon-fed are at best 'good horses', if not mediocre or worse. I talked a lot about the process of becoming 'independent' (and what it does and doesn't mean) in the article on case 31, so I'm not going to repeat all that. In brief, though, the idea is that, while it's immensely helpful to have a strong relationship with a teacher at all stages in practice, we also want to own our practice - to take responsibility for exploring spiritual questions for ourselves, rather than relying on someone else to solve all our problems. Sometimes, a Zen teacher will test a student to see if the student is still dependent on the teacher's approval. (This can be a painful process for the student if they're still attached!) And, in fact, we have an example of this kind of test in the Zen literature. In case 30, a monk named Damei goes to Mazu to ask for instruction - 'What is Buddha?' Mazu answers 'The very mind itself is Buddha.' Damei takes that away, practises deeply, and comes to a profound realisation. Eventually, he moves away from Mazu's temple to set up his own practice place. Later, around the time of case 33, Mazu changes his teaching method, and starts to say 'Not mind, not Buddha' - contradicting his previous teaching, which had perhaps become a bit of a cliche by that point. Hearing of this, a monk goes to find Damei, and says 'Hey, I heard you trained with Mazu. What did he teach you?' Damei says 'The very mind itself is Buddha.' The monk smirks, and says 'Oh yeah? Well, these days it's different!' Damei politely says 'Oh, what does he say now?' The monk says 'Not mind, not Buddha!' Perhaps he's feeling pleased with himself, for having heard the advanced teaching, whereas Damei still has the beginner's stuff. But Damei isn't impressed - he says 'Well, the old fool can keep it. As far as I'm concerned, the very mind itself is Buddha!' That's independence in the Dharma - a realisation that you know for yourself beyond any doubt, that nobody gave you and nobody can take away from you. When you arrive at this place, it doesn't matter what anyone says, they won't convince you that you've misunderstood, any more than someone can persuade you that you don't actually like your favourite food, or your favourite music. It's just totally obvious to you - not as a matter of blind faith, but as a matter of fact. OK, but why 'Not mind, not Buddha'? There's more to Mazu's new slogan than an elaborate way of trolling his former students, however - and we can see this in another story about Mazu. A monk asked, 'Master, why do you say that mind is Buddha?' Mazu said, 'To stop babies from crying.' The monk said, 'What do you say when they stop crying?' Mazu said, 'Not mind, not Buddha.' The monk asked, 'Without using either of these teachings, how would you instruct someone?' Mazu said, 'I would say to them that it's not a thing.' The monk asked, 'How about when someone comes who has finished all of these?' Mazu said, 'I would teach them to experience the Great Way.' And what is the Great Way? 'The very mind itself is Buddha.' Practising with all this craziness Believe it or not, we can actually turn the story above into a concrete practice exercise. It's in several parts, and you may find that you need to spend a long time at a particular stage before moving on to the next part. That's fine - as you've already seen, it's ultimately a circular investigation, so wherever you are right now is fine. (Actually, it might be better to think of it as a spiral - each time around, you go a little deeper. Or, if you're mathematically inclined, you might prefer the image of a fractal, like the one shown above. As you zoom in to any part of a fractal, sooner or later you find yourself back where you started - a fractal contains infinitely many 'copies' of itself at deeper and deeper levels of 'zoom', just like Zen practice.) So here's one suggestion for how to work with this second story in a practice. Set yourself up in a meditation position, maybe take some time to get settled and focused, and then turn your attention to the practice themes given below. 1. Mind is Buddha Notice the sensations in your body, coming and going. Notice the sounds around you, coming and going. Notice the thoughts moving through your consciousness, coming and going. Notice the visual impressions - either what you see through open eyes, or the flickering behind closed eyelids, both are equally fine - coming and going. Now, notice that you are aware of each of these phenomena arising and passing. By definition, you must be - if you weren't aware of a sound, it wouldn't be there for you to notice it. By the time you notice it, you're already aware of it. So now ask yourself: what is it that is aware? What is it that 'knows' these impermanent phenomena? Who or what is 'witnessing' these momentary experiences? What is this 'awareness', which seems to be always present? Notice further that, while a particular experience may be disturbing or unpleasant on some level, the awareness itself is not disturbed - the disturbance is another, separate, arising within awareness. Awareness itself accepts whatever arises, calmly and freely letting it pass through. Our awareness actually already possesses the very qualities we might associate with awakening - clarity, equanimity, acceptance, even love. As we become more familiar with this awareness, we may find that we can come to 'rest in awareness' - panoramically aware of whatever comes and goes, but not pulled into the details of what's going on, not disturbed by whatever arises in your experience. You can simply abide as awareness, at peace. This is one meaning of 'mind is Buddha'. You have it already - all you have to do is to learn to rest in it. 2. Not mind, not Buddha However, we don't stop there. There's a subtle trap - we can turn 'awareness' into something special, something 'apart' from reality, something transcendent or other-worldly. Our practice can become an escape from the world, rather than a way of being in the world more freely and effectively. So, once you've established a clear sense of 'mind is Buddha', we then turn our attention to investigating what this 'awareness' actually is. Where is it? Is it a physical thing, and if so, does it have a shape, or a colour, or a size? How much does it weigh? Or is it something more like a thought, and if so, which thought is it, out of the multitude of thoughts arising and passing every minute? Can we, in fact, find anything which is truly separate from the phenomena of our experience - the sights, sounds, thoughts and feelings? This is a strange investigation, because ultimately there's nothing to find - and yet that's an unsatisfying answer, and one which must be seen many times before it really sinks in. Seek and don't find, seek and don't find, over and over, until ultimately we are forced to acknowledge that the 'mind' in which we were taking refuge in step 1 doesn't really seem to exist. 3. It is not a thing Once we have a sense of the unfindability of the mind, we can then go even further, and extend the same kind of investigation to everything else. We tend to regard ourselves as inhabiting a world of things - solid, fixed objects with dependable properties. But what do we actually experience? A momentary stream of sights, sounds, tactile sensations and thoughts, here today and gone tomorrow. From those experiences we form a kind of belief in the 'things in themselves' - but is this something we actually experience, or just an inference? The purpose of this stage of practice is not to refute the material existence of the world, but to explore more deeply how we experience the world, to see how we create something that isn't actually there by weaving together the information from our senses into something which is more than the sum of its parts. We come to see how the mind creates the sense of separation that leads us to believe that we are individual, disconnected things in a world of things - and we find that we can let that sense of separation soften and dissolve, until we arrive at a new way of seeing in which we're not separate at all. 4. Entering the Great Way - mind is Buddha Where do we go from here? The third step can be a bit unnerving, as the seeming solidity of the world we've inhabited for our whole lives starts to dissolve in front of our very eyes. At this point it's possible to miss the mark, and go down a rather nihilistic path - 'nothing really exists, everything is illusion, there's no point to anything.' At this point, one of the old Zen teachers might well whack you with a stick - does that sudden sharp pain exist, or not? If not, why are you glaring at me and rubbing your arm? But if so, then what happened to 'nothing really exists'? In fact, the aim of Zen is far from nihilistic. I'm not trying to convince you that nothing exists - I'm trying to show you how it really exists. Our experience of the world isn't nothing - it's this, here, happening right now. It's spring flowers, warm summer days, the chill of autumn, the frost of winter. It's the countless joys and sorrows of a human life, making our way through the world moment by moment, dealing with whatever life is throwing at us right now. It's what it always was - the only difference is how we relate to it. Do we spend our days fighting against a cold, hard, inflexible world of things which are never quite arranged to our liking, or can we flow with the unfolding of the universe, playing our own unique melody amidst a vast orchestra of sound all around us? The point is not that the world doesn't exist - the point is that our experience of the world is inseparable from the world itself. The way we relate to the world is the world, from our own subjective standpoint. To see this clearly - in effect, to recognise that the very mind itself is Buddha - is to be awake, to enter the Great Way. May you enter the Great Way soon - the world needs more people who see it through the eyes of a Buddha.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

SEARCHAuthorMatt teaches early Buddhist and Zen meditation practices for the benefit of all. May you be happy! Archives

June 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed