Five things to do at the end of a meditation sessionLast week we looked at five things to do at the beginning of a meditation session, using a list from my teacher on the Early Buddhist side, Leigh Brasington. Leigh also has a list of five things to do at the end of each session, so let's take a look at those too!

(You can find Leigh's own thoughts on these steps on his website - what follows will be my interpretation of the same principles.) 1. Review (Leigh's term for this is 'recapitulation' but I find 'review' easier to remember.) So, you've made it all the way to the end of your meditation session without screaming, throwing your timer at the wall or giving up and going for a walk. Well done! But before you rush off to do something else - and, by the way, if you've had a difficult sit, notice how much more relaxed you feel now that the bell has rung, even though almost nothing has changed yet - it can be helpful to review what just happened. First up, what was the state of your body and mind at the beginning of the session (and, more broadly, especially off retreat, what were you bringing with you to the cushion)? Were you highly agitated, sleepy, hyper-caffeinated, ill, short on time? What effect did that have on the practice? Do you notice trends emerging over time (e.g. every time you sit down to do Silent Illumination when you're tired, you fall asleep without fail)? Next, what was your practice or practices? What happened during the course of the meditation? Did your mind settle? If you were doing a samadhi practice, did you enter jhana or an equivalent state? If so, how did you get there? (It's worth noting that Leigh teaches jhana retreats, and so in that context this step is mainly about looking at the quality of your jhana practice. The hardest part in the early days of jhana work is figuring out how to get into the first jhana at all, and so taking time to review which approaches worked and which didn't can be invaluable. Each person ultimately learns their own route into jhana, so it's essential to have a degree of introspection into the mechanics of your personal practice. That said, the same is true of other practices such as the Brahmaviharas too, so the review step is useful for all practitioners, not just people learning the jhanas.) 2. Insights (Leigh puts this step third, but to me it makes more sense for it to flow naturally from the reviewing process.) Something else to consider is what you learnt from the practice - whether any insights cropped up. Insights can come on the relative level, telling you something about yourself (for example, the discovery of a deep psychological mechanism which has been making unhelpful life choices for you for twenty years), or on the absolute level, telling you something about the nature of experience itself (for example, that all experience is mind-originated and we are not fundamentally separate from the rest of the universe). Insights are tricky beasts. An insight is not the same as an experience - we can have a dramatic experience in meditation and learn nothing useful from it, or we can have a profound, life-changing insight with no experiential fireworks whatsoever, just a simple falling-into-place of understanding. When we do have an insight, it's useful to take some time to reflect on it. My Zen teacher Daizan strongly recommends keeping a meditation diary and taking a few minutes for a 'brain dump' after every sitting, making a note of anything useful that you've learnt. At the same time, though, we should be careful not to over-intellectualise what we've learnt in practice. Meditative insight is transformative only when it's experiential in nature and fully embodied in our day-to-day life - otherwise it rapidly becomes just another spiritual trophy on the shelf, a story to tell other practitioners about 'that time I saw emptiness' to show what a great meditator you are. 3. Impermanence (Leigh puts this step second, so I've switched Insights and Impermanence.) One of the central insights in all forms of Buddhism is the impermanent nature of the phenomena of our experience. Everything comes and goes - civilisations, nations, loved ones, the food we eat, each breath we take. Nothing is ultimately stable or reliable, and trying to hold on to something and force it to be solid, dependable and permanent is a recipe for suffering. Thus, we take a moment to recognise the impermanent nature of all things. Your practice is now over. Even if jhanas arose during the practice, they're gone now; if the practice has left you feeling peaceful, content or joyful, that's beautiful, but it too will pass sooner or later. While this might seem like a bit of a downer (what's the point in practising contentment if I'm just going to feel stressed again later?), it's really an opportunity to appreciate and celebrate whatever positive or beautiful qualities we experience in our practice and our lives right now, precisely because we know they won't be around forever. Sooner or later it all goes away, whether or not we choose to take a moment to enjoy it - so isn't it better to make sure we do take that moment when we can? Impermanence is also particularly important to recognise if we've had an insight (noted in step 2) which was bound up in an experience. Experiences come and go, but insights change the way we see the world, and the deepest ones can't fully be un-seen or forgotten. However, if we associate the insight with the experience, we might start to feel like we're 'losing our awakening' when the experience wears off. 4. Dedication of merit In last week's article we saw how Leigh's suggested things to do before a sitting helped to create a positive, supportive environment for meditation in part by connecting our practice to a wider context beyond ourselves. In the same way, the dedication of merit at the end of any period of practice is a traditional Buddhist ritual used to re-connect ourselves with our wider community. Sometimes I'll end a day-long retreat by ringing a meditation bell three times and saying 'May any merit from our practice today be for the benefit of all beings.' But wait, what's this 'merit' stuff? And where did this suspiciously religious-looking ritual business come from? The concept of karma is found throughout Buddhist teachings - and it often means subtly or even wildly different things depending on the era of the text you're reading or the teacher who's talking about it. In modern-day Thailand, for example, it's common to hear people talking about 'making merit' by doing good actions, like if you do enough good stuff then it 'balances out' the bad stuff you've done on some set of cosmic scales. (I read a book once where the main character was involved in activities that she regarded as creating negative karma, but it was to earn money to send her highly intelligent kid brother to university so that he could become a doctor and help many people, and by her calculations the positive karma he would create through his work would outweigh the negative karma of her actions, so she regarded it as a net positive.) In the Pali canon, we find the Buddha talking about karma (kamma in Pali) as 'intention'. He points to something that modern neuroscientists also recognise - whatever we do frequently becomes habitual, as our minds become trained to move in that direction naturally and instinctively. So if we routinely meet difficult situations with anger, we'll be more likely to respond with anger in the future, whereas if we practise responding with compassion instead, we'll be more likely to display compassion instinctively in the future. Personally, I find this a more useful way to relate to karma than the 'cosmic scales of justice' thing, because otherwise we have to explain why bad things happen to good people and so forth, which gets into multiple lifetimes and all that jazz. Whatever you think about karma, though, the ultimate purpose of practice in the Buddhist context is the alleviation of suffering - and, with my Zen/Mahayana hat on for a moment, not just our own suffering, but the suffering of all beings. Our practice goes far beyond ourselves - the changes we make in ourselves are reflected in our relationships and interactions with other people, and those people will go on to interact with others, and on and on - the web of influence that spreads out from our personal thoughts, words and deeds reaches far and wide. So it can be worth taking an explicit moment to remember that web of interconnection at the end of a practice. Even if you've just had the best sit of your life, experienced lots of wonderful jhanas or had lots of deep insights, this isn't ultimately about how great you are, and please don't run around telling everyone how much more enlightened you are than them. Dedicate the merits of your practice to the benefit of all. The interesting thing about this work is that, the more you give it away, the more you have... 5. Continuing mindfulness In the context of a jhana retreat, off-cushion mindfulness is really important, because the concentration that you build up in your meditation practice is easily frittered away if you return to a scattered state when the practice ends. If you're trying to learn the jhanas, it's helpful to have the best concentration you can possibly muster, which means guarding the sense doors and paying attention to what you're doing between sits. More generally, perhaps the biggest pitfall for experienced meditators is to 'compartmentalise' the practice. It can be easy to think that, because you meditate for twenty minutes every day, that's all you have to do - and yet, after a few years, you start to notice that you have a lovely experience whenever you go on retreat, but it all falls to bits when you come back to daily life, despite your best efforts to hold on to whatever peace of mind you found on the retreat. But if you've established a boundary between your 'spiritual life' (which happens all day on retreat, but only for 20 minutes a day off retreat) and 'normal life', even unknowingly, you'll tend to find that most of the benefits of your spiritual practice are confined to those moments when you're engaged in your 'spiritual life'. Ultimately, the practice goes far deeper if we widen our sense of 'spiritual life' to include everything that we do. Our relationships, our work, our most mundane activities can all become opportunities for practice - which is not to say that we start having artificial conversations with our loved ones because we're trying to 'practise compassion' or whatever, but simply that we continuously work at bringing clear, bright awareness and total presence into whatever situation we find ourselves in, rather than spending most of our lives only half there, always thinking about what we'd rather be doing. In the long run, we do this practice not to reach some final point where we don't have to practise any more. Rather, we practise so that this way of relating to our experience - with presence, clarity and openness - becomes who we are. May all beings benefit from the merit of our practice!

0 Comments

Five things to do at the start of a meditation sessionWhen my teacher Leigh Brasington is leading a retreat, a few days into the practice he'll introduce a list of five things to do at the beginning of each sitting. It's a neat little list that does a great job of setting up supportive conditions for any meditation practice, so let's take a look and see what's in there!

1. Gratitude It's very helpful to begin your practice by cultivating a positive mind state. Whether you're interested in samadhi, insight, heart-opening, energy practice or something else, it all tends to go better when you're starting from a place of well-being. Negative states tend to reinforce contraction, grasping and clinging to old habitual patterns of thinking and behaving, whereas positive states tend to open us up to new possibilities. Thus, Leigh recommends starting every meditation practice by generating a sense of gratitude. How you do this is really up to you, but here are some starting points for consideration:

So another approach is simply to cast your mind back over the last few days and pick out three or four small things for which you can feel some degree of gratitude. Even if this is hard at first, please persevere, because you'll find it gets easier over time, as you train your mind to notice and remember little incidents throughout the day that would otherwise be overlooked and forgotten. 2. Motivation Why are you doing this? What brings you here, to this website, to this article? More generally, what brings you to a meditation practice? This inquiry can actually be a complete practice in itself (as can most of the items in this list, with the possible exception of the next one). You can work with 'Why am I here?' as a koan, just like 'Who am I?' or 'What is this?' (Koan practice is discussed in the latter part of this article.) However, for today's purposes, we're going to take it in a slightly different direction - koan practice is more about the exploration of the question than the answers we arrive at, but if we're looking at our motivation as a preliminary to a meditation practice, it can be more helpful to arrive at some kind of answer, even if it's only a provisional one. We are meaning-making creatures. We like things to make sense, to be contextualised in a wider frame, to be part of a broad narrative that tells us who we are and what's going on. Generally speaking, people who feel that their lives are meaningful tend to report higher levels of subjective well-being than those who feel that life is meaningless and arbitrary. And, interestingly, people who spend time assigning meaning to things tend to report the subjective sense that their lives are more meaningful. In other words, by actively relating to our lives as meaningful, we feel that they are, indeed, meaningful. You may have heard the story of the janitor at NASA who, when asked why he was working so late, replied 'I'm helping put a man on the moon.' Now that's meaning! So - why are we here? What is the meaning of our meditation practice to each of us as individuals? Are we here to find a way out of suffering? To explore a rich and fascinating historical wisdom tradition? To learn things about ourselves and how our minds work? To find peace of mind? 3. Intention Leigh's term for this one is 'determination', but I'm personally not so keen on that word. Perhaps it's because my natural tendency is to try a bit too hard, but whenever I think of 'determination' I get a kind of anime-esque image of myself enwreathed in a halo of flames about to transform into my most powerful form. Then I tend to charge headlong into my meditation practice like a bull in a china shop, totally lacking the subtlety needed to navigate my internal landscape. So let's not do that. But it's still useful to take a moment to set a firm, clear intention for our practice. In the previous step we reminded ourselves why we're here. Now we should get clear about what we're going to do. What is your practice for this sitting? Are you going to cultivate samadhi, do an insight practice, something else? It's all too easy to sit down to meditate, start your timer, and then fifteen minutes later realise that you've been lost in thought and haven't actually started meditating yet. Deliberately setting a clear intention at the beginning of each sit can really help to avoid this pitfall. Having a clear intention in mind can also help if you find yourself getting bored part-way into the sit. This is especially a problem if you have a sizeable toolbox of different practices (which is the way I teach, so the longer you hang around me, the more prone to this problem you'll be - sorry!); it's easy to think 'Ahh, this body scan thing isn't really working, I'll do some jhana practice instead. Hmm, nope, jhanas don't seem to be happening, how about some noting? Ugh, this is making me agitated, maybe I'll do some metta.' And ultimately you end up spending the entire session jumping from one practice to another, never settling into anything properly. One last point worth mentioning is that part of your intention-setting can include a reminder to treat yourself kindly when you notice that your mind has wandered. As I mentioned in a previous article, if we beat ourselves up whenever we notice our mind has wandered, we'll ultimately train ourselves to be less likely to notice mind-wandering - because who wants to get yelled at? The intention-setting stage of practice can be a good time to remind ourselves 'For the duration of this sitting, whenever I notice that my mind has wandered, I will consciously celebrate that moment of clear mindfulness before returning to my practice', or something like that. (It sounds cheesy but it really works - try it!) 4. Metta / loving kindness Of the five, this is the step that Leigh is 100% adamant that you should never, ever skip. Leigh's recommendation is that you should always do metta for yourself, and optionally for others if you have time and feel so inclined. Actively cultivating loving kindness is a central practice in early Buddhism, and it can be powerfully transformative. By cultivating love within ourselves, we become less dependent on external sources of validation and affection; we also become kinder, friendlier people to be around. A deep enough metta practice can also lead us to states of samadhi and deep insights into the nature of dualistic perception, so don't be tempted to write it off as 'just some hippie thing', even if it isn't really to your taste at first. It took me a long time to 'click' with metta practice, and honestly it'll probably never be in my top three go-to practices, but equally there have been times when metta practice has been exactly what I needed in the moment, and my practice would be impoverished without it. You can find out some more about metta on the Brahmaviharas page in the Early Buddhism section of this website. There are also a couple of 10-minute guided metta practices on my Audio page - one based around visualisation, the other using phrases. A third approach is simply to generate the felt sense of wishing someone well, and rest in that feeling. By the way, metta isn't just a great practice in its own right, it's also serving an important purpose at this stage in Leigh's list of preliminaries. We started by generating a positive, relaxed, open frame of mind with gratitude, but the motivation and intention-setting stages can sometimes have a kind of 'sharpening' effect, generating a certain amount of intensity and 'spiritual urgency'. It's helpful to have this kind of energy fuelling our practice, but as I said above, we don't want to go too far in this direction. So bringing in metta at this point will tend to soften everything back down again, making us flexible rather than overly rigid. 5. 'Breathing in I calm body and mind, breathing out I smile' The final step is a 'gatha' - a short verse recited mentally in rhythm with the breath. The use of a gatha is a practice popularised in modern times by the Vietnamese Buddhist teacher Thich Nhat Hanh, and indeed this particular gatha comes from him. Reciting a phrase in this way acts as a support for mental focus, in much the same way as counting the breathings. Unlike counting the breaths, however, the meaning of the gatha is also intended to support the practice, reminding us to move towards relaxation and well-being. (Leigh has commented that this particular gatha is potentially all the instruction you need to enter jhana - one of Leigh's preferred techniques for entering jhana is to focus first on stilling the mind to the point of access concentration whilst smiling, then shifting the attention to the pleasantness of the smile itself as a route into the first jhana.) So this is the final part of the 'on-ramp' for your main meditation practice - having cultivated gratitude, set up the frame of motivation and intention, and opened up the heart with metta, we now let go of all of that and simply focus on breathing, relaxing and smiling, calming the whole mind-body system down and letting us slide smoothly into whatever comes next. How long should I spend on all this? There's no single answer to that - as I mentioned above, steps 1, 2, 4 and 5 could potentially be complete practices in themselves. If you never got past the gratitude step for the rest of your life as a meditator, there are worse ways to spend your time! In general, though, we're looking for these to be preliminary steps, and once you've done each one a few times you should be able to move fairly quickly through them. In a 30-minute meditation session, you might want to spend a minute or so cultivating gratitude (perhaps a little more if you're coming to the practice in a negative frame of mind); once you've clarified your motivation sufficiently, it only takes a few moments to reconnect with that, and likewise with the intention-setting. For metta, Leigh would recommend that the absolute minimum is a minute focusing on yourself, longer if you have more time and/or would like to include other people. As for the gatha, it depends a little on how busy your mind is and where you're going next. In the same way that if you're working with the breath, you might start out by counting the breaths and then later drop the count once the mind is a bit more settled, you'll tend to find that you reach a point where the gatha is no longer supporting the practice and actually starting to get in the way. Certainly if you want to move on to an insight practice, at some point you'll have to shift gears and let go of the gatha to make space for the insight practice. But there's no particular formula (35 seconds of gratitude, then 12 seconds of motivation, then...). Rather than looking at these preliminaries as a rigid set of obligations that you have to drag around with you like chains, see them instead as optional supports. As you learn more about your own mind states and the effects that these preliminaries have on them, you'll develop an intuitive sense of how much of each one is 'enough'. So give them a go and see what works! Is it OK to enjoy meditation? What if I don't want to?There's more than one way to meditate, as anyone who has perused the dizzying array of practices on Insight Timer or YouTube will know. Within the Buddhist traditions alone, we find concentration/samadhi, insight, heart-opening and energetic meditation techniques, along with other related techniques like contemplation.

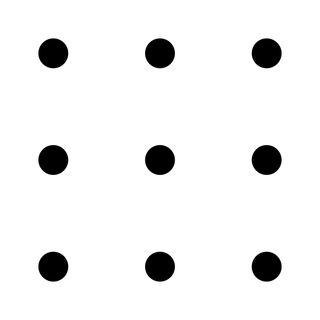

Different constellations of these techniques show up in different traditions. For example, early Buddhism has jhana practice for samadhi, the Four Foundations of Mindfulness for insight, and the Brahmaviharas for heart-opening, but not much in the way of energetic practices. Rinzai Zen, on the other hand, mainly stresses insight and energetics (Hakuin's 'two wings of a bird'). Within traditions, too, different teachers will have different emphases and different go-to practices to share with their students. (You can see my standard offering for new meditators in my free book Pathways of Meditation.) But, in such a saturated marketplace, how are you supposed to know which techniques to practise, and what difference does it make anyway? The Buddha's advice on different paths of practice In the Pali canon (the oldest records of the teachings of the historical Buddha), we find a discourse (AN4.163 if you want to read the whole thing) which sets out some of the different paths available to us. "Mendicants, there are four ways of practice. What four? 1. Painful practice with slow insight, 2. painful practice with swift insight, 3. pleasant practice with slow insight, 4. pleasant practice with swift insight." To me, the fourth option sounds the best, no question! But actually there are arguments to be made for each approach. Some of us are naturally more drawn to the unpleasant aspects of life. The historical Buddha initially became interested in practice precisely because of the problem of human suffering - sooner or later, all the things we love change and vanish, and we get old, sick and die, so what's the point of any of it? Why love anything when you know it's just going to be taken away from you? If this is your orientation, a meditation practice which is primarily pleasant might actually feel inappropriate or unhelpful - a kind of spiritual bypassing, just sitting there with your head in the clouds ignoring the problems all around you. If you came here to study suffering in detail, then a practice which puts the microscope on the painful aspects of your experience might be a much better fit for your interest, and much more motivational (especially at first), than the cultivation of love or bliss. On the other hand, some of us are here because we already feel bad and would like to feel a little better. If this is you, then cultivating love, compassion, contentment and joy might be exactly what you're looking for, and infinitely more appealing than the alternative. There's even some nuance in the slow/fast distinction. Awakening is often framed as a goal at the end of a path, and when we look at it that way, it's only natural to want to move down that path as rapidly as possible. Whole traditions have set themselves up as 'the fast path to enlightenment' throughout the ages, playing into exactly this sentiment. My teacher's teacher, Shinzan Roshi, would sometimes encourage people to achieve kensho (initial awakening) quickly, both for their own good and the good of those around them. When we hear things like this, it can give rise to samvega, a kind of 'spiritual urgency' which can be helpful in giving us the energy to practise and the motivation to focus on our meditation rather than getting lost in distraction. However, this way of looking has some drawbacks too. It sets up a situation in which we're deficient right now, trying to get somewhere to find a thing we don't have. The urgency of samvega can easily turn into a frantic grasping which actually tightens the mind and body rather than opening it. And we can become oblivious to our own needs and the needs of those around us in a way that's very unhelpful, ultimately becoming selfish and distant rather than open-hearted. Reportedly, the Dalai Lama was once asked what was the quickest way to enlightenment, and in response he burst into tears. Taking our time, proceeding slowly and carefully, can sometimes help us to avoid these negative excesses, whilst also giving us enough time to integrate what we're learning fully into our lives instead of simply chasing the next insight. So what are the pleasant and unpleasant approaches? Returning to AN4.163, the Buddha goes on to describe 'painful practice' thus: And what’s the painful practice [...]? It’s when a mendicant meditates observing the ugliness of the body, perceives the repulsiveness of food, perceives dissatisfaction with the whole world, observes the impermanence of all conditions, and has well established the perception of their own death. (Readers familiar with the Satipatthana Sutta will recognise some similarities with some of the suggested exercises in the first foundation of mindfulness.) What's being suggested here is a form of insight practice: a deep inquiry into the body, its nutriment and the things of the world, recognising their fundamentally unsatisfactory nature (dukkha), an investigation of impermanence (anicca), and the contemplation of death. By contrast, 'pleasant practice' is described as follows: And what’s the pleasant practice with slow insight? It’s when a mendicant, quite secluded from sensual pleasures, secluded from unskillful qualities, enters and remains in the first jhana, [...] (The whole passage is quite long, so I won't quote the whole thing here, but you can find a slightly shorter version of the standard formulation in my article on jhana practice.) What's being described here is samadhi practice, specifically the cultivation of the four jhanas, since this is a discourse from early Buddhism and that's their approach to samadhi. So the Buddha seems to be suggesting that insight practice is likely to be 'painful', whereas samadhi practice is likely to be 'pleasant' - and experientially this does seem to be pretty accurate. The modern proponents of 'dry insight' practices like Mahasi noting will tend to trumpet how effective these practices are for generating lots of insights pretty quickly, but at the same time will talk about the negative side effects of the practice (sometimes called the 'dark night', a term borrowed from the Christian contemplative St John of the Cross). By comparison, jhana practitioners (like my teacher Leigh Brasington) tend to have a much better time of it, since their practice involves training the mind to rest in positive states for extended periods, and seem anecdotally to have much less difficulty with the bumps along the spiritual road. (As an aside, it's also interesting - and important - to note that you don't need to do the 'unpleasant practice' - i.e. formal insight meditation - to get even 'swift insight'. The yoga tradition of Patanjali described in his Yoga Sutras is a very deep samadhi practice with very little in the way of 'insight techniques', yet from Patanjali's descriptions it leads to the emergence of insight nevertheless. We talk about 'insight meditation', but insight is an outcome, not a technique. Insight meditation can lead to insight because it involves actively investigating some aspect of our experience which has been found to be fruitful over 2,500 years of exploration; but samadhi can just as easily lead to insight because it involves training, sharpening and quieting the mind to the point that we can see what's going on far more clearly than usual.) What about the slow/swift thing? The speed of progress depends on many factors. One is simply the amount of practice we do - more tends to move things along faster than less. My practice noticeably accelerates if I double the amount of sitting I'm doing each day. (Conversely, when someone is going through a difficult patch of practice - perhaps the aforementioned dark night - it can help to reduce the dosage a little bit to make things more manageable.) Another is our intention - if we are clear about why we're sitting, we tend to see clearer benefits than if we just sit out of habit or because we think we're supposed to for some reason. Going back to AN4.163, however, the Buddha suggests another reason: "they have these five faculties weakly: faith, energy, mindfulness, concentration and wisdom. Because of this, they only slowly attain the conditions for ending the defilements in the present life." (And conversely, by having those five faculties strongly, a practitioner may swiftly attain the conditions for ending the defilements in the present life, which is just another way of talking about awakening.) We can interpret this passage in a couple of ways. In many of the classical sutras and commentaries, you'll find practitioners split into three categories - those of inferior, middling and superior spiritual capacities. Those of inferior capacities are traditionally said to need simpler instructions, take longer to understand the ultimate truth, and so on. (Often you'll find texts saying 'That tradition over there is designed for inferior types; we've got the good stuff, but it's only for superior types!') But this rather fixed way of categorising people is pretty limited, in my humble opinion. The whole point of the Buddhist concept of emptiness is precisely that we aren't fixed, enduring entities with permanent qualities that simply can't be changed. We're much more like processes than entities. And so if, right now, someone is finding that their 'spiritual faculties' of faith, energy, mindfulness, samadhi and wisdom are a little on the weak side, that doesn't mean they're doomed to a life in the 'inferior spiritual faculties' club. A few weeks ago I wrote about the seven factors of awakening, and how we could see the subsequent factors emerging naturally from the earlier ones. Rather than trying to develop one-pointed samadhi on the breath simply through force of will, we could instead approach our practice as taking an interest in our breath, and allow the one-pointed samadhi to develop as a consequence. In just the same way, approaching our meditation practice with the right attitude helps our spiritual faculties to develop as a consequence of our practice, rather than a prerequisite. Going back to the earlier discussion of pleasant and unpleasant practice, this is why it matters that you choose a practice that speaks to you, rather than one that doesn't. If the practice looks interesting and appealing, you'll more easily trust that it's going to be helpful for you (faith), you'll be more motivated to do it and to keep going when it gets tough (energy), you'll pay more attention to what's going on (mindfulness), you'll focus on the practice better (concentration) and you'll learn more as a result (wisdom). Conversely, if you're forcing yourself to do something you think is stupid, you won't have any confidence that it's going to be useful, you'll give up when you get bored, you'll only be half there when you aren't totally lost in mind-wandering, and you'll learn nothing of value. So this stuff really matters. When you're starting out, explore what's on offer. Be critical. Try things out. Figure out what speaks to you, and go with that. Don't keep jumping around forever, though - by all means take your time choosing your means of transport, but at some point you have to set off on the journey. And remember to notice the scenery along the way! Getting a better grip on what's going onA couple of years ago, someone in my meditation class with a deep personal practice commented how strange it was that 'sitting and doing nothing' could be so transformative. And we laughed... but his comment stuck in my mind, and I've spent a lot of time reflecting on it ever since. What actually are we doing here? We talk about insight and seeing the true nature of reality - but how is that even possible, and even if it is, why does meditation help us to do it? Meditation practice clearly does something, after all. You can find any number of books in which people describe the profound spiritual experiences that changed their lives forever. Often these experiences involve unusual, altered states of consciousness, in which things appear 'more real' than before, and there's a sense of 'waking up' to a 'deeper truth' that was previously hidden from us. But why should altered states of consciousness be given any credence at all, let alone be regarded as life-changing? We enter an altered state of consciousness every night when we go to sleep, but we don't typically regard our dreams as revealing a 'real truth' to us - if anything, dreams are easy to dismiss as a kind of 'mental garbage'. (I've kept a dream diary for a while, and most of my dreams are pretty lame remixes of whatever's been happening to me lately. Not terribly exciting, and not particularly insightful!) But why do we dismiss dreams, yet accept spiritual experiences? Both are private experiences - you have them, but the people around you don't notice anything different to usual. And both are completely out of line with 'consensus reality' - the generally agreed-upon version of 'how things are'. In a nutshell, what makes meditation and spiritual experiences different from dreams is that they're insight-producing. Dreams might be interesting but are not terribly useful. Insight, however, changes the way we see ourselves, our lives and the world around us for the better - it helps us to get a better grip on what's going on. What the heck is insight? Take a look at this picture. Can you find a way to connect all nine dots using exactly four straight lines? (If you give up, the solution is here.)

Whether or not you've seen this problem before, the first time you encountered it you probably had a hard time with it. You try all the obvious things, but they all seem to need at least five lines. It's not until you're able to make the mental leap to 'think outside the box' (this problem is the origin of that expression) that you can solve it. What's going on here? When we first look at the nine dots, our minds tend to see a square, and thus draw a kind of implicit boundary around the nine dots. That boundary delimits the 'playing area' for the problem, and so we try to find a way to work inside that space to connect all the dots. But that boundary is something that we put there, not something that was imposed by the problem. In essence, we unconsciously self-limit in such a way that the problem becomes insoluble. Even being told 'think outside the box!' is unlikely to help us, because we're doing this unconsciously - we don't realise we're self-limiting, so it's very hard to move beyond that limitation until we finally see it for ourselves. Transparency and opacity We say something is 'transparent' if we can see through it. In the case of the nine-dot problem, our limiting belief that we have to work 'insight the box' starts out as a 'transparent' constraint. It's there, but we don't see it - we look straight through it to focus on the problem. It's only when we're able to notice the constraint - when the constraint becomes opaque - that we understand how we've been limiting ourselves, and can move beyond it. We can explore transparency and opacity in another way too, in a way that's going to be relevant for meditation practice. To do this exercise, you'll need two objects - a cup and a pen. You'll be doing the exercise with eyes closed, so read the instructions first! 1. Close your eyes, and begin to tap the cup with the pen. You're trying to explore the cup in a tactile way, using the pen - just by tapping it, you're trying to get a sense of what shape the cup is. Really put your full attention into the cup. (Notice how effortlessly you can do that - how quickly the pen becomes a part of you, and your whole focus goes into the cup.) Spend maybe 15-20 seconds doing this. 2. Then, continuing to tap, shift your attention into the pen. Feel the pen moving as you continue to tap - put your full attention into the pen, now ignoring the cup as completely as you can. Spend another 15-20 seconds here. 3. Then, still continuing to tap, shift your attention into your hand. Feel the sensations in the hand and fingers as they move, holding the pen, tapping the cup. Put your attention as fully into your hand as you can. Spend another 15-20 seconds here. 4. Now we'll go the other way - continuing to tap, shift your attention back into the pen. Again, spend 15-20 seconds here. 5. Finally, shift your attention back into the cup again, and spend another 15-20 seconds here. This simple exercise illustrates how we can shift our reference frame very quickly and easily, almost effortlessly changing what is transparent and what is opaque in each moment. We started out with the cup opaque, and the pen and fingers transparent; then we made the pen opaque (and largely forgot about the cup); then we made the fingers opaque (and largely forgot about the pen); and then we went back the other way again. What does all this have to do with meditation and insight? We see the world through a particular conceptual frame, based around the idea of duality. I see myself as a separate individual, living my own life, with the rest of the world 'out there' and generally not terribly in line with how I want it to be. And we've seen the world this way for so long that it's become completely transparent to us - it's simply obvious, natural, just how the world is. Except it isn't. It turns out that this is a form of self-limiting constraint that our minds are imposing on our experience in order to help us navigate it, based on an over-emphasis of the mind's powerful ability to divide and compare. And what meditation is intended to do is to help us make this self-limiting constraint opaque, and then move beyond it and its many drawbacks (suffering, isolation, alienation, feelings of inadequacy and insufficiency... the list goes on). We can take a couple of different approaches to try to bring about this shift. Our starting perspective is the conventional one - I'm an entity in my own right, you're a different entity in your own right, and so on. From there, we can either 'go small' or 'go large' in our attempts to break out of our self-limiting prison. To 'go small', we can use what some teachers call the 'event perspective' approach, where we look at the phenomena that come and go in our experience in more and more detail. For example, we could work with the sensations of the breath in the deconstructive way I described in a previous article. As we dive further and further into the micro-sensations of the breath, moment to moment, we arrive at a seething flux of phenomena, constantly in motion, nothing fixed, solid or ultimately reliable, and nothing which we can honestly call 'me' or 'mine' - simply a field of rapidly changing sensations. And if we can get down there deeply and clearly enough, we may see our minds constructing the usual 'entities' that we experience out of that sea of ever-changing phenomena, and know clearly that the usual perspective of duality is not 'just how things are', but is simply the mind's projection. To 'go large', we can use the 'mind perspective' instead, where we look at that which is aware of all events. In the cup experiment, we shifted our transparency/opacity up and down the hand, the pen and the cup - this approach is asking us to shift back one step further beyond the hand, to that which is aware of the hand - the source of all experience, the ground of being. The mind itself must become opaque. To do this, we might use a practice like Silent Illumination. As our practice deepens, and we settle into mental and physical stillness, our minds naturally begin to let go of self-imposed concepts and boundaries, and we naturally shift into unification, oneness and finally the ultimate stillness and clarity of the Buddha Nature itself. (Instructions for several approaches to mind perspective practices can be found in a previous article.) This is the promise of the world's great contemplative and spiritual traditions - that we can come to see through our implicit, self-limiting constraints, and arrive at a totally different relationship with the world, one which is more useful (and in a deep sense truer) than the conventional perspective. So what are you waiting for? (Parts of this article were inspired by John Vervaeke's lecture series, Awakening From The Meaning Crisis.) |

SEARCHAuthorMatt teaches early Buddhist and Zen meditation practices for the benefit of all. May you be happy! Archives

June 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed