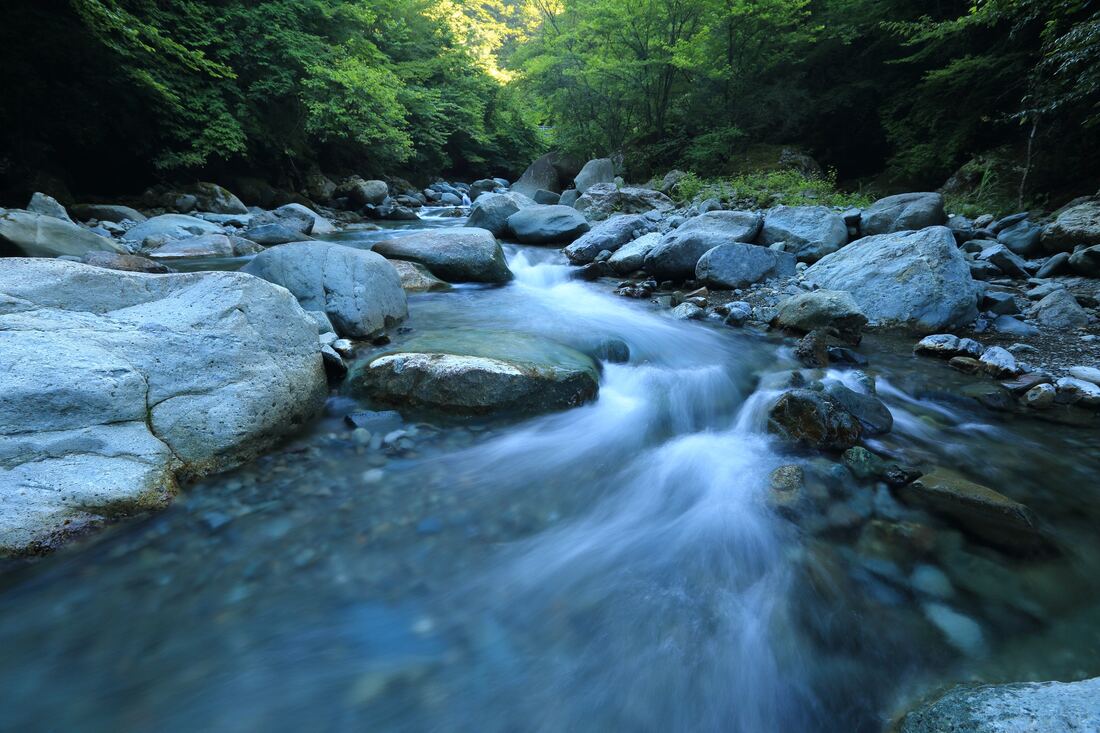

Opening to life's natural flow

This week we're looking at one of my favourite koans in the Gateless Barrier, case 19, 'The normal is the Way'. It features two characters who we've seen before, one several times - Zhaozhou showed up in case 1 (giving a puzzling answer to a question about Buddha Nature), case 7 (telling a monk who was asking for a Zen teaching to go and do the washing up), case 11 (where he tested the realisation of two hermits), and case 14 (where we also met his teacher Nanquan for the first time).

In today's story, however, Zhaozhou has not yet become the profoundly realised Zen practitioner that we've seen in those previous koans. Rather, he's earlier in his practice career, asking perfectly reasonable questions and getting frustrating answers from his teacher, just like the students in the other koans. Perhaps it's a sign of my own insecurities as a practitioner, but I like that we get to see this younger, less experienced (and perhaps more relatable) Zhaozhou, sitting alongside other koans where he's at the height of his considerable powers. We also find his teacher, Nanquan, in a kind and patient mood. (If you've read case 14, you'll recall that last time we met Nanquan he cut a cat in half to stop his monks arguing!) Zhaozhou has a string of questions - but rather than shout at him or hit him with a stick (as we might imagine Yunmen might have done), Nanquan does his best to give a kind of explanation. Of course it isn't totally straightforward - it would hardly make for a good koan if it were! - but I like the fact that Nanquan is trying to lead Zhaozhou forward gently. I've always responded better to teachers who take that approach with me! So let's get into the story and see what's going on. After the last few which were pretty short, this one gives us a fair bit to work with, so we'll take it one piece at a time. What is the Way? When Buddhism arrived in China, it encountered the native philosophy/religion of Daoism. The word 'Dao' translates as 'Way' or 'Path'. There are many such Ways; each profession is said to have its own Dao (the Way of pottery, the Way of accountancy), each animal has its own Dao (the Way of a tiger is quite different to the Way of a sheep), and so on. Encompassing all of that, however, is the Great Way, the Way of Heaven, the universal Dao. Daoist texts such as the Daodejing and Zhuangzi are concerned with pointing to this Great Way so that Daoist practitioners can learn to live in harmony with the universe, and thereby attain peace. According to some sources I've read, Buddhism was initially regarded as a form of Daoism by the Chinese, and Daoist language found its way (no pun intended) into Chinese Zen (aka Chan Buddhism). Some of the Daoist terminology is somewhat repurposed in Zen, so we should be careful about placing too much emphasis on the similarities - it's not really accurate to say that Daoism and Zen are 'the same', although they share much in common. Nevertheless, there's a strong family resemblance, and most Zen folks will find much to appreciate in Daoist writings (and vice versa). So Zhaozhou opens this exchange by asking his teacher 'What is the Way?' This is one of those questions like 'What is Buddha?' or 'What is the meaning of Bodhidharma's coming from the west?', which is really used symbolically - we could equally well say 'How should I practise Zen?', 'What is Zen?' or 'What is the meaning of life, the universe and everything (and don't say 42)?' It's an invitation for the teacher to offer whatever teaching suggests itself in the moment, as opposed to asking about a specific point of practice or doctrine. The normal mind is the Way Nanquan replies that the 'normal mind' is the Way. (In other translations we find 'ordinary mind'. Same difference.) Readers familiar with case 18 should recognise this theme straight away. It's in the same spirit as 'Just breathe naturally' - on the face of it, the answer seems to suggest that there's nothing at all that needs to be done; one should simply do whatever comes naturally. But, as we explored in that article, if that's the case, why do we need to practise at all? And is it really OK to do whatever comes to mind? Seems like that could be a recipe for trouble! I won't rehash the whole of the previous article here - go back and read it if you want to see a more detailed explanation. The basic point here is that there's a distinction between the habitual mind, which is plagued by reactivity and fettered by negative learnt patterns of behaviour, and the natural mind, aka the normal or ordinary mind, which has let go of that reactivity and conditioning, and can instead respond freely and spontaneously to whatever arises, coming from a place of generosity, compassion and wisdom rather than greed, hatred and delusion. Can it be approached deliberately? So far so good - this 'normal mind' thing sounds great. But Zhaozhou has an obvious question - how are you actually supposed to get to this 'normal mind'? Is there a method for the cultivation of the ordinary mind? Again, I really like this question. It's very human. I've read quite a number of Zen (and Daoist) texts and come away thinking 'Wow! That sounds amazing!' But then, when the initial thrill has worn off, there's the inevitable question: 'OK, so now what?' Unfortunately, Nanquan's answer probably isn't going to spark joy for most of us. If you try to aim for it, you thereby turn away from it So here's the central problem. The ordinary mind, by definition, responds spontaneously to circumstances. There's no method for that - the moment you reach for a method, you've already moved away from a spontaneous reaction which is wholly tailored to the situation. Contrary to the stereotypes of what it means to 'be Zen', there's no single strategy that will magically resolve all of life's difficulties. To make matters worse, though, the very search for such a strategy gets in the way of the natural mind. By looking for a one-size-fits-all way of being in the world, we're simply trying to replace one set of conditioned responses with another - a little like trying to learn good information to replace the bad information we previously had. Zen is asking something much more radical of us - that we let go of strategies completely, and take each moment as it comes. As it says in the Daodejing (chapter 48): In the pursuit of learning, every day something is acquired. In the pursuit of Dao, every day something is dropped. Less and less is done Until non-action is achieved. When nothing is done, nothing is left undone. The world is ruled by letting things take their course. It cannot be ruled by interfering. If one does not try, how can one know it is the Way? Zhaozhou is perhaps getting a little frustrated at this point. It seems like Nanquan's answer didn't really help at all. He started by saying 'just behave naturally', and when Zhaozhou asked 'OK, but how do I learn to do that?', Nanquan is saying 'You can't learn to do it - even trying to learn to do it is already moving you in the wrong direction.' And so, not unreasonably, Zhaozhou is wondering how this is supposed to work. If there's no method, if you can't act deliberately in order to reach the Great Way, then how will you ever know if you've made it? Once again, we're back to the central problem: if there's nothing to do, what's the difference between that and never having practised? A less compassionate koan might already have stopped, leaving us to chew on 'The ordinary mind is the Way', or even 'If you try to aim for it, you thereby turn away from it.' Fortunately, Nanquan was in a compassionate mood that day, and so gives us more to work with. The Way is not in the province of knowledge, yet not in the province of unknowing. Knowledge is false consciousness; unknowing is indifference. This is a fascinating answer, because it cuts directly to the heart of the matter. Nanquan rejects both sides of the duality implicit in Zhaozhou's question. He says that the Way is not something that can be 'known' - but, at the same time, that doesn't mean it's 'unknowable'. 'Knowledge', he continues, 'is false consciousness.' In other words, when you 'know' something, you don't really 'know' it. Huh? Zen is full of sayings like 'mountains are not mountains, rivers are not rivers'. But of course they are - that's why we call them mountains and rivers! That's what the word means! But what the Zen folks are getting at is that the word 'mountain', or even the concept of a mountain that the word points to, is not the same as the actual mountain. In order to identify a mountain as a mountain, you move from the direct experience to a concept about the experience - and, in so doing, you reduce the specific, unique mountain that's in front of you to an element of a generic category of 'mountains'. More generally, as soon as we think about something we must, by necessity, separate ourselves from that thing. But if we simply allow ourselves to be in the experience, there's no need for that conceptual gap between 'me over here, thinking about the experience' and 'the experience over there'. To use a spiritual cliché, we become one with the experience. And Nanquan wants us to be clear that there's a difference between this 'being one with' and simple ignorance. 'Unknowing is indifference,' he says - obliviousness, inattention, lack of interest. The 'normal mind' that Nanquan wants us to find is absolutely not a matter of stopping caring or giving up on the world and just doing whatever comes to mind, no matter how harmful it is to ourselves or to others. We cultivate mindfulness for a reason! Indeed, in Nanquan's closing salvo, he reaffirms that the Great Way absolutely is something that we can align ourselves with, and there's a meaningful difference between the experiences of alignment and misalignment. It's just that the difference between the two is not a matter of knowledge, not a matter of having a particular idea in mind that separates you from all the dummies who have the wrong ideas. Rather, it's a way of being - letting go of the separation between us and the experience, and finding ourselves in a place which Nanquan describes as 'like space, empty and open' - no barriers, no separation, no obstacles. Simply the unfolding of experience. The flow state There's a clear parallel here with the 'flow' state described by psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, who spent a great deal of time studying the types of experience that people reported as being most enjoyable and most effective. His book on the subject is very good and surprisingly readable, but in brief, flow is a state characterised by the following:

As the second point notes, in flow there's no 'knowledge' in the sense that Nanquan means it - there's no gap, no split, no separation between you and what's happening. There's simply the unfolding activity. What Nanquan is suggesting is that the flow experience can increasingly become our natural state. We can learn to find our way into this 'ordinary mind' and then rest there, at first only briefly, but eventually for longer and longer, until it becomes our default way to be in the world. It's perhaps a little ironic that the flow state, which is considered rare and exalted in Western psychology, is regarded as the mind's 'ordinary' condition in Zen - but perhaps that's just a sign of how far out of step with the Great Way our modern society has become. One thing is for sure - the flow experience is rewarding enough that there's really no need for 'affirmation and denial', as Nanquan points out. When we're in flow, we're so fully engaged in the flow that there's no space to ask 'Wait, am I in flow yet?' - if you have to ask, you ain't there yet. But once you are, you don't need to ask any more. So don't delay - enter the Great Way today!

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

SEARCHAuthorMatt teaches early Buddhist and Zen meditation practices for the benefit of all. May you be happy! Archives

June 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed