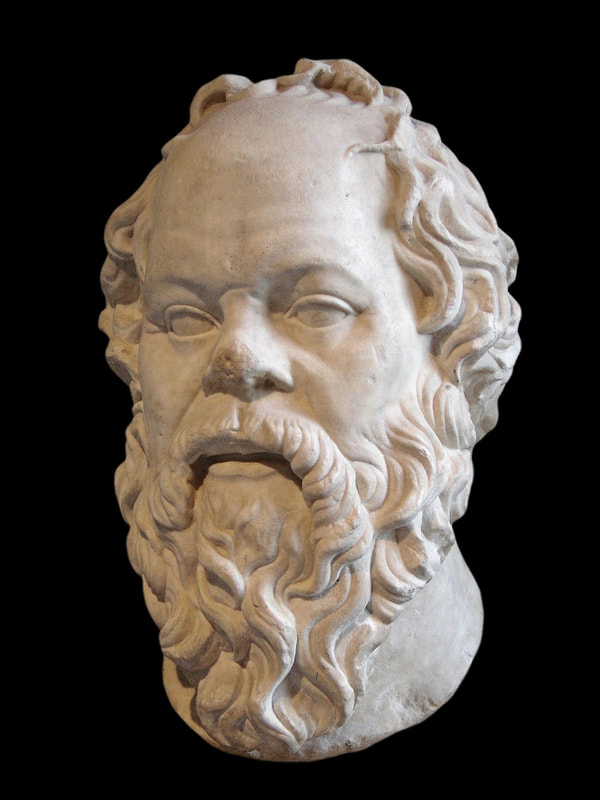

How radical questioning can save us from self-deceptionImage from Wikipedia, courtesy of user Sting; Portrait of Socrates. Marble, Roman artwork (1st century), perhaps a copy of a lost bronze statue made by Lysippos; CC BY-SA 2.5. Socrates was a Greek philosopher from Athens who lived in the 400s BCE - roughly the same period of time as the historical Buddha - and is widely regarded as one of the founders of Western philosophy. It's fair to say that the way we think about things even today is shaped in large part by Socrates (and those who came after him, like Plato and Aristotle). And, in many ways, the work of someone like Socrates is a more natural fit to the modern Western mind than Eastern figures like the Buddha, Bodhidharma (the semi-legendary founder of Zen) or Hakuin (one of the most important Japanese Zen masters in the Rinzai Zen lineage).

Despite the great gulf in time and space between Socrates and Bodhidharma, however, there's an aspect of Socrates' work which dovetails beautifully with the essential project of Zen - peeling away our false beliefs about who we are, what life is and what it means to be happy. Shortly before his death, Socrates famously said 'The unexamined life is not worth living' - but how should we examine our lives? The Socratic method Socrates was deeply interested in truth - but not just any old truth, a certain kind of truth. Socrates was interested in how to life the good life - how to be a good person, what it meant to live a life of virtue and meaning. He was relatively uninterested in the work of the Natural Philosophers (a kind of forerunner of modern-day scientists), who could tell you what something was made of and how it worked, but not how to live a good life. And he was deeply critical of the Sophists - those who studied the arts of debate and persuasion, but in a rather mechanical way; a Sophist could teach you how to convince someone to agree with you, but not whether you actually should! (We only need to look at the world of politics to see plenty of finely honed debating skills employed for the sake of personal gain rather than the flourishing of humanity.) Socrates could see the people around him pursuing their busy lives, doing this and that, each searching for happiness in their own way - but often struggling, suffering, chasing the wrong things, looking for happiness in places that clearly weren't satisfactory to them. (The historical Buddha made exactly the same observation, of course.) And so Socrates started to inquire into truth itself - how we can know something to be true, and what it means to make decisions from a position of wisdom rather than ignorance. The method he came up with for doing this - the famous Socratic Method - looks like it would have been pretty annoying to be on the receiving end of! Picture the archetypal annoying four-year-old child, who just won't stop asking 'But whyyyy?' - except that the people Socrates was questioning didn't generally have the option of saying 'Because mummy and daddy said so, now it's time for bed.' Here's a typical example, lifted wholesale from John Vervaeke's lecture on Socrates. Socrates would come up to somebody and say "Well, what are you doing here?" "Oh, I'm in the marketplace!", his unwitting victim would reply. Socrates: "Well, why are you in the marketplace?" Victim: "Well, I'm purchasing something!" S: "Well, why are you purchasing something?" V: "Well, I want to get these goods!" S: "Well, why do you want these goods?" V: "Because they'll make me happy?" (Now the claws come out.) S: "Oh, so you must know what happiness is?" V: "Well happiness is pleasure, Socrates, I guess! And these things give me pleasure!" S: "But is it possible to have pleasure and still find yourself in a horrible situation that you really dislike?" V: "Well of course, Socrates, that's possible!" S: "Oh, so then happiness isn't pleasure! You're being coy with me! Tell me, tell me, what is happiness?" V: "Oh it's, you know, it's getting what's most important to you!" S: "Well that means that you have to have knowledge. Is it any kind of knowledge?" V: "Well no, it's the knowledge of what's important!" S: "What's truly important? Or what you only think is important?" V: "I guess what's truly important, Socrates!" S: "OK, so, what's that knowledge of what's truly important called?" V: "I guess that would be wisdom, Socrates!" S: "Oh, so, in order to find happiness, you must have first cultivated wisdom! Tell me how you cultivate wisdom and what wisdom is..?" V: "AAAAARRRRRRGGGGGGHHHHHHHHH!" (This last exclamation signifies that Socrates' latest debate partner has fallen into a state called Aporia, literally 'lacking passage', i.e. 'no way to move forward'. Compare this with the Zen koan from the Mumonkan: 'How can you proceed on further from the top of a hundred-foot pole?') 'All I know is that I know nothing' and Great Doubt Socrates is often misquoted as having said 'All I know is that I know nothing,' and taken in that light, we might see Socrates' method as a kind of cruel one-upmanship, a way of showing how much cleverer he is than you by tying you up in knots of confusion, tripping you up with your own words. But that's not really what he's up to. A better translation of his famous saying is 'What I do not know I do not think I know' - and anyone familiar with Zen might recognise the resonance with its concept of Great Doubt. What Socrates is pointing to is that, generally speaking, we lack secure foundations for what we think we know - and yet we act as if it's a sure thing. We pursue what we believe will make us happy, all too often failing to realise that it isn't actually working. Essentially, we deceive ourselves - and it's this self-deception that Socrates is trying to overcome. When we arrive at the point where we no longer think we know what we actually don't know, we throw off the shackles of false, limiting beliefs about who and what we are, and we gain the capacity to open to what's really going on, in all its mystery and wonder. We can see exactly the same dynamic going on in another koan from the Mumonkan: One night Tokusan went to Ryutan to ask for his teaching. After Tokusan's many questions, Ryutan said to Tokusan at last, "It is late. Why don't you retire?" So Tokusan bowed, lifted the screen and was ready to go out, observing, "It is very dark outside." Ryutan lit a candle and offered it to Tokusan. Just as Tokusan received it, Ryutan blew it out. At that moment the mind of Tokusan was opened. "What have you realized?" asked Ryutan to Tokusan, who replied, "From now on I will not doubt what you have said." This koan symbolises our tendency to rely on others - we often believe what we do because we heard it from someone else; we approach teachers to receive the wisdom that we believe they hold and we do not. Here, Tokusan is pestering the master Ryutan with many questions, in the hope that if he just asks the right one, he will gain the missing piece of knowledge that Ryutan has been concealing from him, and will finally become enlightened. Unwilling to go out into the darkness (presented as physical darkness, but an allegory for the intellectual darkness of not-knowing) all by himself, he again turns to the teacher to offer him a light. But at the crucial moment, Ryutan snatches the light away from him, and Tokusan is forced to confront the darkness in a moment of wordless surprise. As it happens, Tokusan was ripe for awakening, and this sudden dislocation out of the comfort zone of knowledge and certainty was enough to catapult him not just into darkness but all the way through the darkness into the light of awakening. Overcoming self-deception Why do this at all? Why question everything, especially if the result is to arrive at the uncomfortable-sounding place of Great Doubt? Because it turns out that the way we decide what's relevant to us - and hence what informs our decision-making - has nothing to do with whether or not it's true, and thus our capacity for self-deception is limitless. And only by noticing this startling disparity can we start to train ourselves to see more clearly and accurately - to make relevant what is true. Our minds categorise perceptions according to their 'salience'. Right now, you probably aren't paying attention to the sensations in your right foot - although after reading this sentence, maybe you are! Your right foot suddenly became salient because I called attention to it; previously, it wasn't remotely salient, so it wasn't part of your experience at all. We've talked many times before about how our experience is fabricated - our minds select which particular stimuli out of the available soup of sensory information are going to be woven into our direct experience in any given moment. And this is a really good thing - if it didn't happen, we would immediately be overwhelmed. Think about a time when you've been in a noisy environment surrounded by too many conversations and you can't pick out the one you're trying to focus on - and now imagine that you could never focus on anything, never select any particular piece of information out of the sea of events. Doesn't sound much fun, does it? It turns out that salience is highly adaptive. Maybe you've heard of the yellow car phenomenon - normally you don't see yellow cars much at all, until you start thinking about buying one, and suddenly it seems like half the world is driving yellow cars! Yellow cars became significantly more salient when you started thinking about buying one, and so now you're noticing every single one, rather than mostly ignoring them. Unfortunately for us, many of our sources of salience are not particularly helpful. We learn a lot of what to pay attention to and how to behave from the people around us - and it's fair to say that we aren't living in a particularly enlightened society. But we're also constantly bombarded by advertisements and other messages from people who have made a life's work of studying the manipulation of salience - people who know how to make a catchy slogan or earworm, something that your mind just won't put down once it's found its way in. And so our salience is constantly hijacked by what other people are telling us to think, believe, feel and desire. We believe what the media tells us to believe (or our alternative, non-mainstream news sources, if we're so inclined - but either way it's the same mechanism), we want the things that the people around us want, we do the things that everybody does, and because everybody calls this 'happiness' we do too, even if on some level we can tell it isn't quite working for us. And this is how we can deceive ourselves. It's extremely difficult to believe something that we know to be false - try telling yourself that you're actually a small green tomato and see how well that works, even if you try really hard - but we can bias our sense of salience in whatever direction is most convenient for us, regardless of whether that bias has any grounding in truth. If we decide that someone is unkind, we start to notice every little unpleasant thing they do - all the time gathering evidence to justify our belief - whilst simultaneously ignoring the times when they don't act that way. And, of course, notice that we don't even have to do this deliberately - the input of salience into our experience is pre-conscious, so we aren't necessarily even aware that we're seeing the world through a tinted lens. The Socratic method - and Zen practice - are designed to explore the way we experience reality - what we perceive, why, and whether our perceptions are as accurate and helpful as we believe them to be. Working with a partner and trying an actual Socratic dialogue is a really interesting exercise, but if you'd like to keep things within the remit of Zen practice, a good question to bring into your koan practice is 'What do I know for certain?' So don't delay - experience Aporia today! (This week's article is heavily inspired by John Vervaeke's magnificent lecture series, ***Awakening from the Meaning Crisis, in particular episode 4.)

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

SEARCHAuthorMatt teaches early Buddhist and Zen meditation practices for the benefit of all. May you be happy! Archives

June 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed