Letting go into the flow of lifeThis week we're continuing once again with our discussion of the Anapanasati Sutta, looking at the fourth and final section (or 'tetrad') of practices, before bringing it all together next week in the final article of the year. Each step in the Anapanasati Sutta builds on the ones that came before it, so there will be a few references back to the previous parts (part 1, part 2, part 3) - it may be worth reading those first before proceeding unless you're already familiar with this discourse.

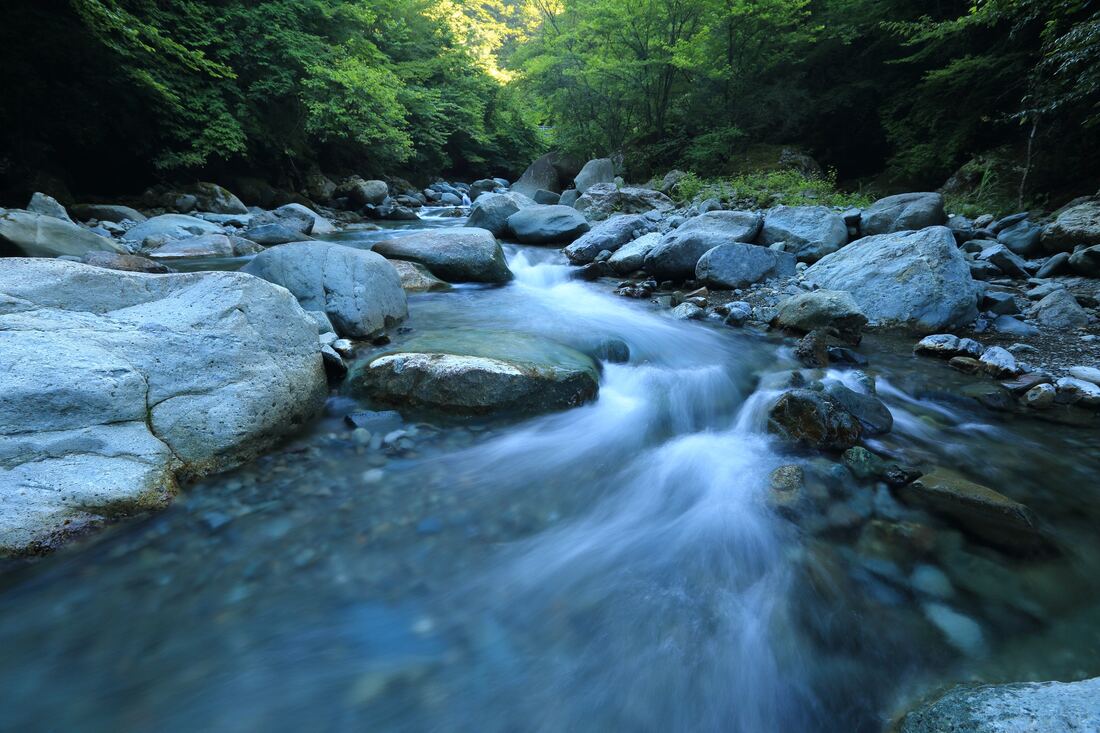

Without further ado, let's get into the Buddha's instructions for the final four steps of this practice! The fourth tetrad, in the Buddha's words One trains thus: 'I shall breathe in contemplating impermanence'; one trains thus: 'I shall breathe out contemplating impermanence.' One trains thus: 'I shall breathe in contemplating dispassion'; one trains thus: 'I shall breathe out contemplating dispassion.' One trains thus: 'I shall breathe in contemplating cessation'; one trains thus: 'I shall breathe out contemplating cessation.' One trains thus: 'I shall breathe in contemplating letting go'; one trains thus: 'I shall breathe out contemplating letting go.' The fourth tetrad is associated with 'mindfulness of dhammas', which essentially means bringing mindfulness to the deeper aspects of the Buddha's teaching, and in the case of the Anapanasati Sutta signals a pivot away from the samadhi orientation of the previous three tetrads (steps 1-12) and toward a greater focus on insight practice for the final four steps. As with each previous tetrad, we continue to use mindfulness of breathing as the 'foundation' of our practice - the constant thread running through all sixteen steps. If we ever find that we're no longer aware of our breathing, that's a sure sign that the mind has wandered, and it's time to renew our intention. As I mentioned last week, if we've been following the first 12 steps up to this point, our minds are likely to be pretty calm and focused by this stage, so we probably won't lose the breath that often. If we jump straight in at step 13 - an approach often called 'dry insight' - then there's likely to be a lot more mind-wandering. The practice will still work, but it's likely to be less efficient and impactful than it would be if we'd spent some time stabilising the mind first. But if, for whatever reason, you just want to go straight for the insight practices without the preceding samadhi component, you can board the anapanasati train at station 13: contemplation of impermanence. Step 13: Impermanence 'Impermanence' is one of those big Buddhist concepts that it's easy to get a very quick intellectual handle on. Everything changes, right? The only constant is change itself. Civilisations rise and fall. The sun rises and sets. The seasons cycle on. (At the time of writing, winter has recently arrived here, and it's gone from being rather brisk outside to positively freezing. Change is also apparent in my wardrobe - the gloves, hat and scarf have now made their annual reappearance.) But, well... So what? Yeah, we get it, things change. Who cares? What's supposed to be insightful about that? From a Buddhist perspective, the contemplation of impermanence helps to undermine our own minds' tendency to want to solidify things. When we meet a person, we form a kind of mental 'snapshot' of who they are - they like xyz, they don't like abc, they do these sorts of things, and so on. If, the next time we meet that person, they're doing something wildly different, it's a confusing experience - this person is exhibiting behaviour that doesn't align with our snapshot of them, which means that either we have to update our snapshot or explain it another way (oh, he was only saying that because he was drunk, that's not who he really is). The truth is that everything is changing all the time, and life goes easier for us if we're able to open ourselves fully to that truth. It means that our minds can't use quite so much shorthand to simplify everything, but it has the advantage that the world appears fresher, newer and more interesting - and, critically, that we aren't caught off guard so much when something changes that we secretly believed should have been totally dependable for all time. One way to open ourselves up to impermanence is to pay attention to the changing nature of our experience in meditation. For example, when we breathe, things are changing all the time. The in-breath has a beginning, a middle, and an end. Then there's a gap. Next comes the out-breath, which also has a beginning, a middle and an end. Then there's another gap. Next is another in-breath - different from the previous one, if we're really paying attention. Maybe it's a bit longer or a bit shorter, maybe we feel the sensations in a slightly different part of the body - perhaps the left side of the nostril is more noticeable than the right side for one breath, then it's the other way around next time. And so on. You can tell that this is working when the breath becomes interesting. At first, it really isn't. You breathe in, you breathe out, you breathe in again - yep, got it, what's next? When we relate to the breath on this conceptual kind of level - 'breathing in now', 'breathing out now' - there's not a lot going on, and so the mind wanders very easily and the practice is dull as ditchwater. But when you connect with the impermanence - the flowing quality of each breath - then each moment is new and distinctive in its own way, and the practice becomes much more like watching a flowing river which is a little bit different every single moment. When you've got a taste for that, we move on to... Step 14: Dispassion / fading away Dispassion is Bhikkhu Analayo's translation; Bhikkhu Bodhi prefers 'fading away'. At first glance these look pretty different, so what's going on? These days, when we talk about 'passion' we typically picture some kind of torrid love affair, or someone who wears their emotions on their sleeve. With that interpretation in mind, 'dispassion' can sound a bit rubbish - like we're going to become an emotionless zombie incapable of feeling love. Yikes. But the original meaning of the term 'passion' is actually 'suffering' - you might have come across the term 'the Passion of the Christ', in relation to the story of Jesus's crucifixion. So, in a Buddhist context, 'dispassion' is ultimately about suffering less. How do we become dispassionate, then? Well, first we have to recognise what causes us to suffer - and, if the Buddha's Second Noble Truth is to be believed, it's our attachment to desire - desire for sense pleasure, desire to become something attractive, desire to get rid of something unattractive. A traditional remedy for such desires is to contemplate their unsatisfactory nature - and, building on the previous step, one way to do that is to recognise their impermanence. Yes, it's nice to have nice things, but sooner or later those nice things will come to an end - will 'fade away', as Bhikkhu Bodhi has it. In practice terms, we might thus shift our attention primarily to the latter half of each breath, noticing that whatever has arisen is subject to passing away. (In the early discourses, a common indication that one of the Buddha's followers has reached the first stage of awakening is that they exclaim 'All that is subject to arising is subject to passing away!' - so this is well worth exploring until your experiential appreciation of impermanence goes bone-deep.) Ultimately, we can thus become aware of the transient nature of everything in our lives. Continuing the river analogy from the previous step (borrowed from Bhikkhu Analayo's book on the Anapanasati Sutta!), it's as if we're now standing on a bridge over the river and watching the water moving away from us. Perhaps we see small twigs and other objects floating along the river; they're here for a while, but the river is carrying them inexorably away from us, so there's no use in getting too attached to them. This, too, shall pass. Again, when we have a clear sense of fading away and the dispassion that comes with it, we move on to... Step 15: Cessation There's a particular power in trying to notice the moment that an experience ends. Typically we don't - we're drawn to beginnings, to arisings, to new things. Sooner or later they always come to an end, but by that time we've already moved on. Carefully skating over the moment of vanishing can help our minds to preserve the illusion of permanence and reliability that I mentioned earlier - and so paying particular attention to that moment of vanishing can help to puncture that illusion more deeply than simply observing impermanence in a broader way. In fact, paying attention to cessation is such a powerful practice that renowned meditation teacher Shinzen Young - who is famous for his vast collection of practices and elaborate systems organising them all together - has said that if he could only teach one practice for the rest of his days, it would be 'just note "gone"'. (You can read more of Shinzen's thoughts on the subject here.) Paying attention just to the vanishing of experience might perhaps sound nihilistic at first sight, but like a lot of seemingly negative practices from early Buddhism, it's actually intended to bring about a more balanced view. There's a practice in the Satipatthana Sutta which is all about contemplating the undesirable aspects of our bodies - translators often use frankly alarming terms like 'contemplating the foulness of the body' to describe it. My teacher Leigh Brasington skips right over that practice when he teaches the Satipatthana Sutta, pointing out (quite rightly) that we already have way too much negative feeling towards bodies in our culture as it is. But the Buddha wasn't trying to body-shame people - he was operating on the assumption that it's quite common for people to 'exploit their bodies for pleasure', as Ajahn Sumedho puts it. We feel down, so eat a bit of chocolate to get a quick lift in mood. We see someone who has a pleasing body, and perhaps that gives rise to lustful thoughts. And so on. So the idea of the body contemplation is to point out that, while there are attractive qualities there, they're also balanced by unattractive qualities that we tend to overlook or brush under the carpet. In just the same way, in the present discourse we aren't choosing to focus on the ending on experiences because we're trying to cultivate a negative view of the world. Rather, we're trying to arrive at a place of balance, where we can see both the attractive and the unattractive qualities of whatever arises. We can appreciate what's here while it's here, but we also know it won't last, and we shouldn't rage too hard against the unfairness of the universe when it does finally pass away. Continuing the 'river' analogy from above, it's as if we've now turned around on our little bridge to face upstream, and we're looking straight down, noticing the very moment when each twig or stone disappears from view as it passes underneath us. In the previous step, we saw things floating away, but slowly and gradually, in a way that could potentially still support a sense of a kind of permanence. Now we're seeing things vanishing, moment by moment, in a way that's impossible to ignore. When we have a clear sense of cessation, we move on to the final step of the discourse... Step 16: Letting go Where has all this practice brought us? We started by tuning in to the impermanence of the world - the shifting, changing, ultimately unreliable and unsatisfactory nature of all things. Then we turned toward the 'second half' of experience - the fading away, the inexorable current of life which will sooner or later take all that is ours, dear and delightful as it might be, away from us. Next, we focused specifically on that moment of disappearance, counteracting our tendency to focus on the new and avoid confronting the inescapable reality of cessation. If we see these things truly, deeply and repeatedly, we arrive at the final stage of the practice - letting go. We realise, beyond any doubt, that it's simply impossible to hold on to anything in this life - possessions, relationships, even our own bodies. In the Zen tradition, teachers often refer to our conventional lives as 'this floating world', which is an image I particularly like. I imagine a kind of village made up of rafts, bobbing up and down on the water currents, lashed together with ropes but forever moving from side to side, always just one bad storm away from coming untethered entirely. We go to great lengths to avoid seeing the world in this way. We make buildings out of stone, brick and concrete, imposing straight lines and right angles on nature's curvature. We use air conditioning to keep our environments at a fixed temperature, immune to the changing seasons beyond the double-glazed windows. And yet, ultimately, all of this is an illusion too. We can't control anything, really. We can't prevent things from changing, nor should we try to - to do so is to deny the innate vitality of the universe, to crush the life out of what we love so that we can somehow preserve it, but in so doing killing the very thing we wanted to save. Rather than approaching life with a clenched fist, trying to hold on tightly and keep things just the way we want them, Buddhism invites us to open our hands instead. 'Letting go' doesn't mean 'getting rid of' - we don't have to give away all our possessions and avoid all relationships 'in case we get attached'. But it also means not imposing, not demanding, not requiring things to be a certain way. We appreciate the good things that come into our lives - perhaps appreciating them all the more for the recognition of their impermanence, rather than taking them for granted until one day they're no longer there. And we endure the bad things that assail us, using the equanimity that we've cultivated through our meditation practice to maintain a sense of perspective that even this is impermanent too. In terms of the river analogy, this is the point where we no longer stand apart from the river, observing it from a distance, but instead slip into the water and allow it to carry us along. May you be carried by life's river..

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

SEARCHAuthorMatt teaches early Buddhist and Zen meditation practices for the benefit of all. May you be happy! Archives

June 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed