Breaking free from the prison of the mind

This week we're looking at case 45 in the Gateless Barrier. It's a simple koan that points to a truth which is both profound and extremely difficult to express in words, for reasons that will soon become apparent!

Spiritual authorities, Zen and 'self-power' Japanese Buddhism makes a distinction between approaches to practice which depend on 'self-power' and those which depend on 'other-power'. A tradition like Pure Land Buddhism is an example of 'other-power'. The basic idea is that if you speak the name of Amitabha Buddha (a celestial Buddha who rules over the Pure Land, a kind of heavenly realm in Buddhist cosmology), then when you die you'll be reborn in the Pure Land where it's really easy to get enlightened. It's an easy method - anyone can say 'namu amida butsu' or 'namo amituofo' - and it results in an easy road to enlightenment. The key is that someone else (Amida Buddha) is doing most of the hard work for you - hence we call this an 'other-power' approach, because you aren't doing the heavy lifting yourself. By comparison, Zen is considered a 'self-power' approach. In Zen, nobody is going to do the heavy lifting for you. A teacher can provide you with a meditation method (like koan study or Silent Illumination), but when it comes to getting the work done, that's all on you. Yes, it helps to have a sangha to practise with, and a teacher to offer support and guidance, particularly if you're going through a tough patch, but fundamentally it's you sitting face to face with yourself, day in, day out, that gets the job done. There's something to be said for both approaches. Awakening requires us to open up to something beyond our conventional ideas of who we are - and it may be helpful for some people to frame that as a kind of grace received from totally outside ourselves. On the other hand, many people who've grown up in a culture heavily influenced by Abrahamic religions find that that approach isn't satisfying, and that they're drawn to meditation practice precisely because it doesn't rely on an external force to intervene on our behalf - and so framing things in terms of 'self-power' might be a much better fit. And, actually, in the long run, the two approaches do kinda meet in the middle. It's said in Japanese Buddhism that even the most ardent devotee of other-power needs a bit of self-power in their practice too, and even the most determined self-power practitioner has to be open to a bit of other-power along the way too. Nevertheless, this koan is very much aimed at encouraging the self-power approach that's characteristic of Zen, and it starts by taking aim at two possible candidates for other-power: the 'past' and 'future' Buddhas. Two Buddhas The 'Buddha of the past' referenced here is Shakyamuni Buddha, aka Siddhartha Gautama. This is the 'historical' Buddha, the man who lived 2,500 years ago in what is now modern-day India, the spiritual teacher who kicked off the whole tradition that subsequently became known as Buddhism. If you're looking for a Buddhist authority figure, you can't go far wrong with Sid himself. At least if we take the Pali canon literally, this is the guy who discovered the Four Noble Truths, came up with the Eightfold Path and introduced insight meditation as a path to enlightenment. The historical Buddha's teachings have been tremendously helpful to me personally, and that's why they're a big part of what I teach, despite this site being called 'Cheltenham Zen'. The ancient teachings of the Pali canon can be a great source of inspiration, not to mention a treasure trove of practical methods for developing generosity, compassion and wisdom. In a broader sense, Shakyamuni represents the tremendous body of wisdom that has been developed and handed down to us over the centuries by the many practice lineages all over the world. The 'Buddha of the future' is Maitreya, a Buddha who currently resides in a heavenly realm, and who is prophesied to come to Earth to revive the Dharma (the true teaching of Shakyamuni Buddha) at a time when the teachings have completely decayed. Plenty of people argue that that's already happened, and several people have claimed to be Maitreya. Whether or not we believe in this kind of prophecy, the point here is that Maitreya represents the promise of future salvation - OK, things might be crappy right now, but if we can just hold on a little longer, Maitreya will come and sort it all out for us - so take a deep breath and keep going! At the symbolic level, both of these represent 'something outside ourselves' that we might secretly hope will solve all our problems. That kind of wish can manifest in a variety of ways. Perhaps it's a subtle sense of restlessness, never settling with any one teacher because maybe the next one will say the right thing to me. The next book, the next retreat, the next empowerment, the secret scroll with the hidden teaching - these all hold the tantalising promise of being 'it', the thing that's going to turn our lives around and enable us to live trouble-free for the rest of time. Zen master Wuzu is gently and compassionately suggesting that, if this is the approach we're taking, we might be looking in the wrong place for salvation. He suggests that both Shakyamuni and Maitreya are 'servants of another' - that's a bold claim, suggesting that even the founder of Buddhism and its promised future Messiah are just underlings in the service of someone much greater. Who could it be - and do they have any books on Amazon?! Zen master Bankei's 'Unborn Buddha-mind' After a period of incredibly intense practice which very nearly led to his death, Zen master Bankei had a profound realisation, which he summarised by saying 'Everything is perfectly resolved in the Unborn.' 'The Unborn' was Bankei's way of referring to what we might alternatively call 'Buddha nature', 'true nature', 'Mind with a capital M', 'awake awareness' or 'pure being'. The Unborn is not something outside of ourselves; we don't need to climb a mountain to find it. In fact, whether we look for it to the north, south, east or west, we're looking in precisely the wrong direction. In order to find it, we need to turn the light of awareness around and look inside ourselves, to find out who we really are at the deepest level. So much for the spiritual cliches - but what does any of this actually mean? Fully understanding Bankei's teaching is, I think, the work of a lifetime - my Zen teacher's teacher apparently once commented that 'Practice is so much deeper in one's seventies than one's sixties', and I'm not even fifty yet, so I have quite a way to go! But we can perhaps get a foot in the door, so to speak, by looking at what lies beyond our thinking minds. Zen often comes across as being pretty anti-intellectual. There's a lot of rhetoric about how thoughts won't help you, and arguably one of the major purposes of koan practice is to frustrate the thinking mind. But the point isn't to eradicate the thinking mind, only to break its stranglehold on our experience. The thinking mind is a wonderful thing. It can figure things out, solve problems, learn skills, allow us to analyse facts dispassionately to overcome unconscious biases - honestly, it's great. I make my living using my thinking mind to solve complex technical challenges, and so I have the thinking mind to thank for the roof over my head and the food in my belly. Thanks, thinking mind! But the thinking mind also has its limitations. The thinking mind sees the world through two major operations: divide and compare. This is different to that, and I prefer the first one. That oh-so-simple mechanism can allow us to do all kinds of cool things - for example, we can project ourselves into an imaginary future to figure out how we want things to turn out tomorrow, allowing us to make plans to increase the chances of things going our way, while taking steps to avoid some of the obstacles that might come up and stop us from getting where we want to be. That's an immense power, and likely goes a long way to explaining the dominance of the human species on this planet. But the world of 'divide and compare' comes with some drawbacks too. Maybe you're familiar with the phenomenon of 'overthinking'. Maybe you've caught yourself planning tomorrow's important meeting for the seventh time - even though the first six runs really did cover all the important stuff. Maybe you've felt that you could be doing better - you have a clear idea of how you should be getting on, and your actual performance falls short by comparison. Or perhaps you're really good at the 'divide' part of the equation, and every time you walk into a room you start finding reasons why you don't belong there, dividing the room into 'them' and 'us' more and more effectively, until 'us' has become 'just me, all alone, unwanted and unwelcome'. So - and bear with me on this for a moment - what would happen if we stopped thinking, even for a moment? How would the world appear to us then, if not viewed through the lens of 'divide and compare'? There are two tricky points here. One, it's quite literally impossible to put that experience into words. This isn't just me being spooky and enigmatic. The moment we start to use words, we have to step back into the world of thought, because that's where words come from. So as soon as we start to 'talk about it', we have to stop 'living it'. But that's not actually as bad as it sounds, because it's like anything else - we just have to experience it for ourselves, and then we know what it's like. No description of the taste of a mango will ever convey the experience of its flavour to someone who's never eaten one, but luckily it isn't that hard to get hold of a mango and try it for yourself, at least in our affluent Western society - if you're reading this article, the chances are that you have access to a mango for the purposes of a taste test. But how the heck do we experience 'not thinking'? That's the second, and altogether trickier, point. At first, we might not even realise how much we're thinking all the time - a very common experience for beginning meditators is for people to think that the practice is actually making them think more than usual, because as soon as we get quiet and start paying attention to what's going on, the thoughts are absolutely everywhere, like an unstoppable mental fire hose thrashing around and spraying thoughts left, right and centre. If you've found this for yourself, let me assure you that the meditation didn't put the thoughts there - they were there already, you just hadn't noticed them. We tend not to notice things that are always there, like the way we rapidly stop hearing the hum of the air conditioning or central heating because it's a steady drone. In the same way, when our minds are bombarded by thoughts, we actually tend not to notice most of them - they just fade into the background of our experience. So first things first, we need to do enough practice that we start to notice our thoughts coming and going, to identify each thought as a discrete mental event with a beginning, middle and end. We can either undertake a meditation practice specifically focused on mindfulness of thoughts, as we discussed in last week's article, or we can simply allow the awareness of thoughts to develop over time as we do another practice, such as Silent Illumination. Once we have some level of familiarity with the contents of our minds, we can then start exploring what happens when we don't have any thought present. If we really pay attention, we'll start to notice moments like this, particularly if we practise meditation for long enough that the mind begins to settle and the thoughts quieten down. We may begin to find that gaps open up naturally between thoughts, and in between is... something else. Perhaps it shows up first of all as a kind of silence - one student described it to me as 'a deafening, horrifying silence', because it was such an unfamiliar and unexpected experience for him. (It doesn't stay horrifying! It's actually quite nice, but it can be a bit of a surprise the first time you encounter it.) Alternatively, if the space isn't opening up by itself, we can sometimes 'trick' our minds into falling silent for a few moments. Spend a few moments noticing your thoughts coming and going, and then ask yourself this: 'What is my next thought going to be?' Everything is perfectly resolved in the Unborn The first step here is to get a taste of this 'deafening silence'. Then, like so many things in meditation, the second step is to figure out how to get back there! It's not at all uncommon to 'stumble' quite easily into some kind of meditation experience the first time, and then really struggle to get back there. It isn't just a case of beginner's luck - often, the problem is that we want to get back to the prior experience so much that the mind actually tightens up and becomes less flexible, thus blocking the path leading back to the desired experience. Fortunately, this is something we can learn to overcome - we 'just' have to figure out how to incline our minds gently towards wherever we want to go, without getting so 'grabby' that we get in our own way. Once you can get back to 'the space between thoughts', even if it's just for a few moments at a time, you can start to explore what it's like. It's a delicate business - remember, you can't use words, because as soon as you do you're back in the world of thought again. (There's nothing worse than finding yourself thinking 'Oh hey, I'm back there in the space between thoughts!', because, of course, you aren't - at least, not any more! But maybe you were, right up until the thought came along, and that's still something.) As you start to become familiar with the space between thoughts, several things become apparent. One, you don't stop existing when you aren't thinking about something! This might sound facetious, but a genuine source of resistance to letting go of thought can be a kind of fear of annihilation. If we live entirely in our thoughts, and then we stop thinking... eek. But give it a try, and notice that it's OK - usually, quite a bit better than OK, actually, but 'OK' will do for now. Two, if you're able to rest in that space for a reasonable length of time, you'll start to notice how simple your experience has become. Although you aren't thinking, you haven't suddenly become stupid, or incapable of functioning. If something needs to be done, it's immediately, intuitively obvious what it is - unless it's a complex problem that genuinely does need to be thought about, of course, but what you'll start to notice is how rarely that actually happens. It turns out that life isn't an endless series of challenges to be figured out - unless we make it so. Third, as you continue to taste that direct, wordless simplicity, you'll start to notice that it feels pretty good. Not 'exciting', like cookies and ice cream, but more of a quality of deep contentment. When we aren't using our thinking minds to compare the present moment to an idealised alternative version of itself, things are just what they are - they don't need to be any different. Unexpectedly, this can be true even if what's actually here is unpleasant in some way. For example, right now I have a bit of a stomach ache, because I've drunk way too much coffee this week and my digestion is a bit upset. If I start thinking about what I should have done instead (like sticking to green tea, which doesn't affect me in the same way), I'll quickly become resistant to and resentful of the present discomfort and my role in creating it. But if I'm simply here, in the space between thoughts, then the pain in my guts is just something else in the room, along with the computer screen in front of me, the music coming out of the speakers, the sensations from other parts of my body, and so on. It's unpleasant, but it's also fine - it just is what it is, no need to make a fuss about it. No need to suffer over and above the discomfort, which is already here anyway. I believe that some combination of the above is what master Bankei is getting at with his statement that 'everything is perfectly resolved in the Unborn'. On one hand, we're quite capable of functioning from that place - despite the lack of thought, we understand what's what and what needs to be done. And in the absence of comparison, things are just what they are and don't need to be otherwise - which is one way to define 'perfect', isn't it? Now, Bankei was a big advocate of 'resting in the Unborn', not just as a meditation practice (although Silent Illumination is an ideal vehicle to practise this way of being), but as a way of life - sit in the Unborn, eat in the Unborn, work in the Unborn, sleep in the Unborn. To what extent that's really possible for someone in a household life, I don't know. (Maybe I'll look back in ten years' time and laugh at how shallow my practice was in my forties!) For me, there are peaks and troughs in the amount of thinking that goes on. Sometimes I'll have long stretches where my daily meditation is pretty quiet. At other times, I'll be in the early stages of a new creative or research project, and my head will be a whirlwind of thoughts (that's where I am right now, as it happens). But sometimes, things quieten down enough that I can connect with that space between thoughts - and if I can do it, you can too. And even if we only have occasional access, it's a very powerful practice to connect with it whenever we can. Whatever we're dealing with at the time, it's quite likely that the situation will seem simpler, and our immediate response more obvious, when we step out of the stream of thoughts. (I've started to think of this as 'asking my Unborn mind what needs to happen next' - perhaps there's a hint of other-power sneaking into my framing there!) Give this one a try and see how you get on. Master Bankei would say that rediscovering your innate Unborn mind is the entire path of practice, and that each moment you spend there is a moment that you already are a fully awakened Buddha. Maybe Zen isn't so difficult after all? May you discover your Unborn Buddha mind today.

0 Comments

Reward-based learning and the BuddhaIn the meditation world, a great deal of emphasis is placed on the present moment. Eckhart Tolle's well-known book is called 'The Power of Now' - it doesn't get much more on-the-nose than that.

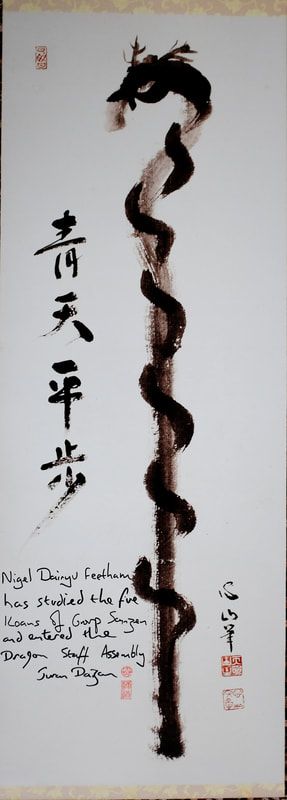

The present moment is certainly an important part of spiritual practice, to be sure. But there's another dimension of practice which can sometimes be overlooked if we focus too much on 'right here, right now' - and that's how the practice can help us to change over time. Pre-enlightenment practices of the Buddha-to-be When looking at the discourses in the Pali canon (the records of the earliest period of Buddhist teachings, and generally thought to be closest to the teachings of the historical Buddha), the Buddha doesn't talk much about his personal practice history. Instead, he mostly focuses on giving practice advice tailored to the audience he's addressing. (Notice the resonance with the role of the teacher as discussed in last week's article!) However, in Majjhima Nikaya 19, the Buddha does talk about a practice that he undertook in the early years of his spiritual journey, before reaching awakening. “Bhikkhus, before my enlightenment, while I was still only an unenlightened Bodhisatta, it occurred to me: 'Suppose that I divide my thoughts into two classes. Then I set on one side thoughts of sensual desire, thoughts of ill will, and thoughts of cruelty, and I set on the other side thoughts of renunciation, thoughts of non-ill will, and thoughts of non-cruelty.' (Readers familiar with the Eightfold Path will note that the Buddha-to-be chose to divide up his thoughts based on those in line with Right Intention and those not in line with it.) The basic premise here is that thoughts can be conceptually divided into two categories: those which support our growth in the directions we wish to move, and those which don't. This is potentially helpful in two ways. Firstly, by getting clear about the types of thoughts we have, we start to develop an awareness of how much time we spend engaging in mental activity that is beneficial and supportive of our aims in life, and how much we spend doing the exact opposite! Then, secondly, we can start to do something about it. But what should we do, and how? Well, let's see what the Buddha has to say. Continuing with MN19: "As I abided thus, diligent, ardent, and resolute, a thought of sensual desire arose in me. I understood thus: 'This thought of sensual desire has arisen in me. This leads to my own affliction, to others' affliction, and to the affliction of both; it obstructs wisdom, causes difficulties, and leads away from Nibbāna.’" (The discourse later goes on to describe the same process for thoughts of ill will and thoughts of cruelty, but to keep things simple we'll focus on thoughts on sensual desire here.) What's being described here is a mindfulness practice - specifically, mindfulness of thoughts. Typically, when thoughts arise in meditation, we simply let them come and go, doing our best not to pay too much attention to them, perhaps remaining focused on an object such as the breath or the body sensations. In this case, though, the practice is actually to look at the thought carefully - but without being drawn into the story associated with the content of the thought. That's tricky! The reason that most meditation practices work with something other than thoughts is because they're so 'sticky' - a thought comes up about something disagreeable that happened to us, and before we know it we're replaying the memory and getting annoyed all over again. At this point, the meditation practice has usually been lost, swept away in the tidal wave of thoughts and emotions associated with the story. Nevertheless, if we're able to pay attention to our thoughts without getting drawn into them (which is possible, with practice), then we start to notice some interesting things. Over time, we can observe where our thoughts lead us. In the example above, the Buddha describes noticing the arising of a thought of sensual desire. We might think 'Well, what's wrong with that? What's wrong with wanting something nice?' Maybe nothing - but you should check it out for yourself! In my case, I've noticed that thoughts of sensual desire often over-emphasise the positive aspects of the experience that I'm craving, and brush under the carpet the negative side. When I see a chocolate cookie, the pleasure I'll experience when I taste it is immediately apparent to me... and I tend not to think about the regret I'll feel when I weigh in the next morning and the scale has bad news for me. There's also a subtler detail that has taken a lot longer for me to notice - which is that, after I eat a sugary snack, my body actually feels pretty bad not long after. The taste is great at first, but it leaves a kind of slightly unpleasant residue in my mouth afterwards - which, ironically, my habits tell me can most easily be assuaged by eating another cookie. Eating too much sugar can also lead to a sugar high, in which both my mind and body become slightly agitated and uncomfortable. It's not a big deal, easily missed - usually missed, because I've gone straight from eating the cookie to focusing on something else - but it's there in the background of my experience nonetheless, making me feel 5% crappier than if I hadn't eaten the cookie in the first place. Humans have a tremendous capacity for selective awareness. I know I do! It's easy to focus on the positive aspects of an unhealthy behaviour - the taste of the cookie, the rush of the cigarette, the thrill of doing something dangerous - and ignore the negative aspects. But something interesting starts to happen if we're able to bring the light of awareness to the totality of a situation. Slowly but surely, we arrive at a more balanced view of what's going on - the good and the bad. This can help to take the sting out of very difficult experiences, as we notice the silver lining to the cloud, and it can also help to reveal the dark side of patterns like unhealthy pleasure-seeking. The Buddha describes coming to this exact realisation. By examining his own thoughts of sensual desire, he discovered that, ultimately, they led to his own 'affliction' - a strong word, perhaps, but the point is that he realised that, in the long run, chasing material sensual pleasures wasn't taking him where he wanted to go - and, looking more broadly, the same pattern seemed to apply to the people around him as well. Becoming disillusioned - which isn't as bad as it sounds! One slightly annoying feature of insight meditation is that it's possible to see something once, twice or even a few times without it really having much impact. Perhaps we notice 'Gosh, things really are impermanent, aren't they?', and yet we're still left with a sense of 'Yeah, but so what?' In just the same way, it's quite possible to notice the negative aspects of some of our behavioural patterns, and to accept fully on the intellectual level that this is something we should probably stop doing... and yet the behaviour still doesn't change. (Unfortunately, I speak from experience!) I once heard a teacher compare insight meditation to a process of conducting a survey. You ask a couple of people what they think about something, and you get a bit of information - but it isn't really enough to draw conclusions from. You ask a thousand people, maybe a pattern starts to emerge - you're starting to get somewhere, but there's still a way to go. By the time you've asked a million people, you've now got a pretty solid basis to draw conclusions. In the same way, each time we observe our experience, we're gathering evidence. Maybe that first glimpse of impermanence doesn't seem like a big deal - OK, you definitely noticed something, but you've spent a lifetime building up the implicit world view of permanence and solidity, and it'll take more than a few experiences of impermanence to really make a difference. But if you keep at it, then sooner or later the sheer weight of evidence you've accumulated becomes undeniable - and that's when things flip around, and your world view changes. And the same applies to behaviour change. The Buddha goes on: "When I considered: 'This leads to my own affliction,' it subsided in me; when I considered: ‘This leads to others’ affliction,’ it subsided in me; when I considered: ‘This leads to the affliction of both,’ it subsided in me; when I considered: ‘This obstructs wisdom, causes difficulties, and leads away from Nibbāna,’ it subsided in me. Whenever a thought of sensual desire arose in me, I abandoned it, removed it, did away with it." By examining his thoughts of sensual desire and noticing that they consistently led away from where he wanted to go, those thoughts began to subside. The Buddha realised that the promise of lasting happiness offered by those thoughts of sensual desire was an illusion - and so he became disillusioned. The experience of disillusionment is generally not a happy one. I experienced a fairly significant disillusionment recently, and it sucked! But - as a friend was kind enough to point out at the time - disillusionment means letting go of an illusion - something that wasn't real in the first place. It's uncomfortable and embarrassing to realise that we've been operating under a false impression all this time, but in the long run it means we're moving into closer alignment with the truth of things - and that's ultimately what this path is all about. And, just like a magic trick that's been seen through, when we become disillusioned with something, it loses its power over us. In the Buddha's case, when he deeply understood that his thoughts of sensual desire weren't taking him where he wanted to go, the thoughts subsided. As we can see, this wasn't an immediate process, like flicking a light switch - the thoughts continued to come up for a while, but each time they did, he reflected on negative consequences, and again those thoughts lost their power. Reward-based learning and habit change The understanding of psychology has undergone some pretty significant changes since the time of the Buddha 2,500 years ago, and this can sometimes lead to a bit of a language barrier when trying to map traditional teachings on to modern concepts. (For example, you might be surprised to hear that there's no Pali word for 'emotion', since the concept didn't exist back then - perhaps that's even shocking, given how central emotion is to our modern understanding of human behaviour.) Nevertheless, MN19 is describing a deep truth about human experience - and one which is now being validated and fleshed out in modern terms by scientists. There's a biological mechanism called 'reward-based learning' (or simply 'reward learning') which is key to how living beings learn to navigate their environment. At the simplest level, 'if it feels good, I should do it again; if it feels bad, I shouldn't do it again'. It hurts to stub your toe, so you learn to try to avoid doing that - which means that, overall, you're less likely to damage yourself. It feels good to spend time with friends, so you learn to do that - which means that humans tend to build communities that support each other and help us to survive by pooling our skills and resources. And so on. While this is probably an oversimplification (if you're more knowledgeable on the science of all this and want to fill in some of the blanks, please leave a comment below!), we can start to see both where our bad habits come from, and how bringing clear awareness to an experience (including its downstream consequences) can lead to behavioural change. We start with that first bite of the cookie. It's sugary - and that's good, because our bodies use sugar as an energy source. Unfortunately we evolved in an environment which didn't have shops selling chocolate on every corner, and so we're biologically geared to load up on resources when they're available, since we might not get to eat tomorrow. That ingrained biological response is then exploited by junk food manufacturers, who take great care to design sweet treats that are as appealing as possible to our old-fashioned instincts. So we take that first bite - and it's good! Reeeeeally good! The behaviour of taking a bite of a cookie leads to a significant positive reward - and by the time we've eaten the whole thing, we've repeated that pattern a few times. Already, our brains are starting to learn 'eating cookie = good, more please!' But this only works if we do what we usually do, which is focus on the pleasant aspects of the experience and distract ourselves (whether deliberately or not) from the unpleasant aspects. If we instead bring mindfulness to the whole experience, then the overall 'reward' of the activity starts to go down - because now we're noticing not just that initial high but then the low that follows it. And if we do this repeatedly (that 'gathering evidence' process I mentioned above), then we can recalibrate our brains to the new reward level. We start to realise that, although the cookie still looks good, actually there are some significant downsides to it as well. Maybe we'll just have one today, rather than the whole bag - or maybe we'll just get a cup of tea instead. For more on reward-based learning, habit change and mindfulness, check out the work of Dr Judson Brewer, who uses mindful approaches inspired by the early Buddhist suttas to help people to quit smoking and make other positive behavioural changes. Closing on a tangent: a few thoughts on pleasure, happiness and the spiritual life It's pretty common for people to object to the idea that sensual desire could be viewed in a negative light. To Western audiences, it smacks of joyless puritanism, asceticism for its own sake, an anti-life philosophy. It's usually easier for people to see why thoughts of ill will and cruelty should be abandoned - but what's wrong with pleasure? One response to this is to say that it isn't about eliminating pleasure from our lives, but about coming to a more balanced appreciation of what's going on. As I've outlined above, eating a cookie is neither 100% positive or 100% negative. It tastes great - that's a nice thing! But it also has some negative consequences - and if we're focusing only on the positive and ignoring the negative, we're deluding ourselves as to what's really going on. When we have a more balanced appreciation of the whole picture, we might still choose to eat the cookie - but we'll be making that decision with our eyes open, rather than sleepwalking into it because we're too distracted by the promise of pleasure. A slightly more sophisticated version of this argument (which is admittedly harder to justify in the context of MN19 above) is that we aren't necessarily trying to eliminate sensual desire, but rather to be free from it. What does that mean? It means that we have a choice in the matter. I've had times in my life when I've been so hooked on caffeine that at 11am every day my legs carry me to the shop at work and my hands grab the Coke bottle out of the fridge and pay for it with my credit card without my conscious intervention - I can watch the process happening, vaguely aware on some level that I'd been planning to cut down on my caffeine intake, yet the habit is so strong that it feels like I'm watching it play out on a TV screen. When we're really hooked on some kind of sensual desire, we really don't have much say in the matter - we're at the mercy of our habits and our environment. Part of the reason for cultivating mindfulness is to bring some agency back into the picture - to open up a space in which we can see our impulses come up and decide whether to act on them. Both of these answers lead to an approach which is eminently compatible with being fully 'in the world'. We continue to have families and friends, jobs and hobbies; and we continue to do things just because they're fun - but this is balanced by the cultivation of mindfulness and a gradually deepening awareness of the full story of how these things affect us. It becomes easier to notice when a 'harmless fun' activity is starting to get problematic - that addictive mobile phone game is starting to take up a bit too much time in the morning, and we're beginning to arrive late for work, or we no longer have enough time to make a healthy packed lunch to take with us, so instead we're going to the shops and buying junk food instead. If there's no problem, there's no problem - but when there's a problem, we're more likely to spot it, and to have sufficient presence of mind to steer ourselves back on track. This is fine so far as it goes. But you won't have to look far to find spiritual teachers and philosophers advocating something much stronger - a deep renunciation of the world, a total cutting off of 'frivolous' activities in favour of solitude and spiritual pursuits. What's going on here? First, I should say that I'm not a monk and have never been one, so I can't really say what the monastic life is like from personal experience. The closest I've come is doing residential meditation retreats, the longest of which have been two month-long retreats at Cloud Mountain Retreat Center in the U.S. - but I think that's long enough to give me a sense of what the more thoroughly renunciate life offers. I've previously offered a model of 'excitation and stimulation' to describe the process of 'settling the mind' in meditation. The basic idea is that, at any given moment, we have some internal level of 'excitation' - from being utterly calm to being excited, terrified or stressed out - and that, in order to meditate effectively, we need to find a meditation technique which offers a level of 'stimulation' (how interesting/engaging/active/busy the technique is) which approximately matches our current level of excitation. If the technique isn't stimulating enough, we get bored and can't stay with it. If it's too stimulating, we actually disturb our minds rather than settling them. Well, it turns out that when you get the mind settled enough - which typically happens for me after a few days on a residential retreat - it feels really, really good. Not 'cookies and ice cream' good, but a different kind of experience - a subtle, beautiful, deeply profound contentment. Like the taste of a mango, you have to have experienced it to know what I'm talking about. But the key point is that, when you're there, it's very obvious that it's a really, really good place to be, and that all of the usual pleasure-seeking activities of your busy life don't come close. And a very natural thought that comes up at such a time is 'Why would I ever want to go back to how things were before?' Because here's the thing - accessing that kind of peace really isn't compatible with going to the cinema at weekends and playing video games in the evenings. Those activities are so stimulating - being aimed at people who are living highly stimulating lives in our busy modern society - that they're utterly destructive to the peace of mind that comes from solitude. Whether or not you've experienced the kind of deep peace that the renunciate sages are pointing to, it isn't so outlandish to believe that if we want to take something to its farthest, deepest extents, we're going to have to make some sacrifices along the way. Suppose you want to play the piano. If you play for ten minutes two or three times a week, the chances are you'll have some fun but you'll never play to a sold-out crowd at the Royal Albert Hall. If you want to be a professional concert pianist, you're most likely looking at practising for many hours every day - and you'll also have to give up any activities that would interfere with your piano playing (for example, anything which has a serious risk of injury to the hands). I remember one point when I was practising both Kung Fu and Tai Chi with the same teacher, and I was having some trouble taking my Tai Chi to the next level of subtlety due to habitual muscular tension in my wrists. My teacher nodded and said 'Yeah, that's a Kung Fu thing, unfortunately.' At that moment I knew I'd have to give up Kung Fu if I wanted my Tai Chi to go deeper - not because Kung Fu was bad and Tai Chi was good, but simply because they were pulling me in opposite directions. (I quit Kung Fu - and while I miss it sometimes, overall I don't regret my decision. Deepening my Tai Chi was very much the direction I wanted to go, and my practice has developed significantly in the years since then.) Getting back to the spiritual life, in the same way as the Tai Chi-Kung Fu example, it isn't that worldly pleasures are intrinsically bad - but, past a certain point, if you want to go as deep as possible in terms of deep states of peace and tranquility, you can't have it both ways. Either you pursue the path of solitude in a very dedicated way, sacrificing a great deal of modern life in the process, or you accept that by remaining embedded in the world you're only going to touch into that place of peace deeply on long retreats. Which is it to be? And I suspect that the way we each answer that question is what makes the difference between those who choose to pursue a truly renunciate lifestyle and those who don't. I have friends who are very strongly drawn to that way of life above and beyond everything else - but I'm not one of them. I'm drawn to the world. I enjoy learning complex technical things and solving problems. I want to play a hands-on role in helping people - and not just in the spiritual world, but in wider society as well. So I have a day job in which I try to solve technical problems in a way that benefits the wider society. I also have hobbies and interests - I really like science fiction (as you can probably tell from some of the references that make their way into these articles), I enjoy writing, making music, playing games with my friends (we just started a Cyberpunk RED campaign that I'm very excited about - note, excited, not peaceful and content!), going to the cinema and so on. I also have a dedicated daily spiritual practice - which brings me the kinds of benefits I've outlined above and more - and at least a couple of times a year I go on retreat, and reconnect with that deeper place of stillness. My personal sense - and I could be totally wrong - is that some degree of that peace and stability does work its way into daily life, maintained by my daily practice and deepened by my time on retreat. And that's enough for me. I find that it's worth the trade-off to give up the full depth of contentment that might be available if I had a more renunciate lifestyle, in order to remain more fully in the world, committed to making whatever small contribution I can to our modern society from within rather than leaving it behind - and enjoying some conventional pleasures along the way too. But that's just me. I don't say this to criticise anyone else's lifestyle choices! Maybe meditation helps you but going on a retreat is a step too far - great, meditation helps you! Or maybe you're making that transition to the more fully renunciate way of life - good for you. Sometimes I wish I could join you! May you find your own path to happiness - whatever that looks like. Postscript: as synchronicity would have it, Zen teacher Domyo Burk has recently uploaded two podcasts on the subject of renunciation and the household life. Check them out: part 1 and part 2. The winding road of Zen practiceThe image above is a painting of a staff transforming into a dragon, symbolising Zen awakening. Copies of this scroll have historically been given to Zen students who have met a certain bar in their practice. Within Zenways, my Zen sangha, it was the practice at one point to give a copy of this scroll to students who'd studied all five Group Sanzen koans, as you can see from Daizan's inscription above. The image is taken from Nigel Feetham's website, used without permission.

This week we're looking at case 44 in the Gateless Barrier, simply titled 'A Staff'. As usual, on the face of it, it doesn't seem to make much sense - but once we get into the symbolism involved, it'll hopefully become a bit clearer.

Giving you a staff: formlessness to form Zen teachers often have a staff, which represents their role as a teacher. More generally, the staff represents a method, a form of practice. When we are first drawn to the spiritual life, we begin in a state of 'formlessness'. Perhaps we have an aspiration - to be a better person, to achieve enlightenment, to find peace of mind - but unless we have a practice of some sort - something to do - it's difficult to make that aspiration a reality in our lives. Traditions like Zen and early Buddhism offer us a whole variety of methods of practice. Perhaps we're drawn to exploring a spiritual question through koan study, or perhaps the holistic nature of the Eightfold Path appeals to us as a way of life. One way or another, in the early stages, we very much need some kind of 'form' - a practice or set of practices that we can undertake consistently over a period of time (weeks, months, years). Here, a teacher is very helpful. Of course we can concoct our own spiritual path, either from a single tradition or by blending together techniques from a variety of sources (just like I tried to 'teach myself' to play the guitar when I was a teenager!). But it tends to be much easier and more effective to find a teacher that we're willing to work with - in an ideal world, a teacher has already travelled at least some of the path that interests you, and they can help to save you time by pointing out the common pitfalls and correcting mistakes that are easily seen from the 'outside' but more difficult to spot from the 'inside'. Different teachers take different approaches to providing 'form' for the student. Some teachers develop systems and curriculums which encapsulate what that teacher understands the Dhamma to be. Other teachers prefer to guide students on a more individual basis, trying to find the forms which best suit that individual. I tend more toward the latter, although I had a bit of a stab at system-building here - in a nutshell, I generally recommend that people have a practice that combines concentration, insight, heart-opening and energetic cultivation, with a strong ethical foundation. In any case, when it's working well, the teacher will be supporting the student to develop in a way that's working well for them. That's the first part of the koan here - 'If you have a staff, I will give you a staff.' At least the way I understand Dhamma teaching, it isn't my job to tell you how to live your life; rather, it's my job to help you work within the life you already have and do my best to support and accelerate your progress. As such, I'm not looking at you as a person with no staff who needs to be given my staff (which is, of course, the best of all staffs) - rather, I recognise that you already have a staff, and I'm just supplementing what you already have, to the best of my limited ability. Taking your staff away: form to formlessness In the fullness of time, practice begins to mature. In the early stages, you're learning 'how to' - you're getting the basic instructions for a practice and figuring out how to do it in the most basic sense. As we continue to practise over the months and years, however, a transition takes place. At the beginning, we're working with a technique that someone else has given us. In the fullness of time, however, the practice becomes our own. We develop our own relationship to it, our own sense of how the practice works, and how best to engage with it in this moment, with this particular set of conditions. This transition reflects a process of integration - a blurring of the boundaries between 'this technique' and 'me'. Gradually, the separation between the two disappears. My daily Silent Illumination practice is no longer a fancy Zen meditation performed with much ceremony and specialness; it's simply how I start each day, sitting quietly and watching my experience. At times I'll find myself sitting in the same way on train or coach journeys, simply observing. There's no real distinction between 'formal practice' and 'informal practice' - resting in awareness has simply become one expression of my life, which emerges when the conditions are right. (Perhaps that sounds a bit grandiose! I don't mean to suggest that I'm incredibly advanced or have an amazing practice, or anything like that. I'm just trying to highlight the way in which my relationship to my practice has changed over the years.) In some ways, this period of practice can even bring up a bit of sadness. The novelty has very much worn off! Indeed, there can be a sense that practice 'used to be more interesting' - particularly when things are first taking off, it's quite common to have lots of deep insights, and to start to feel a bit special as a result. 'Look at me!', you might think. 'All these other suckers don't understand anything, but I know what the Buddha was getting at, I understand all these Zen texts!' The technical term for this stage of practice is 'the stink of Zen'. My teacher's teacher, Shinzan Roshi, would sometimes hold his nose and say 'stinky, stinky!' if people were getting a bit too impressed with themselves. It's an exciting period, but it's also an immature one, and a responsible teacher will typically do their best to bring the student's feet back down to the ground. And that's what the second part of the koan indicates - 'If you have no staff, I will take your staff away'. Early on, a very intense fascination with and attraction to the forms of practice can be very helpful - but past a certain point it simply becomes another kind of attachment, another ego support to make ourselves feel special because of all of our wonderful insights. In the long run, the spiritual path is all about letting go - and that includes letting go of the story of what a great meditator we are. And thus we return again to formlessness - letting go of our attachment to specific techniques, allowing our practice to integrate itself so completely that there's no distinction between 'practising' and 'not practising'. This is a long and difficult journey, and perhaps one that takes a whole lifetime to 'complete' - but it's also a rewarding one. Along the way, we learn the true value of these practices as they manifest in our own lives, not as they're portrayed in ancient texts from other cultures around the world. Gradually, we return to formlessness; this second formlessness is both fundamentally different to, and fundamentally the same as, the first formlessness at the beginning of our practice. As T.S. Eliot put it: We shall not cease from exploration And the end of all our exploring Will be to arrive where we started And know the place for the first time. Through the unknown, remembered gate When the last of earth left to discover Is that which was the beginning; At the source of the longest river The voice of the hidden waterfall And the children in the apple-tree Not known, because not looked for But heard, half-heard, in the stillness Between two waves of the sea. Or, in the words of the great Zen master Bruce Lee: Before I learned the art, a punch was just a punch, and a kick, just a kick. After I learned the art, a punch was no longer a punch, a kick, no longer a kick. Now that I understand the art, a punch is just a punch and a kick is just a kick. Where are you on this journey? Do you have a staff, and if so, do you have the support of a teacher who can ensure that your staff is in the best shape it can be? Or is it time to let go of your staff - and if so, do you have a teacher on hand to point out when you're reflexively grasping at the familiar, comfortable staff that's brought you so far, and to prise it gently out of your grasp? Training the mind

This article is the final one in an eight-part series on the Eightfold Path, a core teaching from early Buddhism. I introduced the Eightfold Path in the first article in the series, so go back and check that out if you haven't heard of it before. (You can find links to all the articles in this series on the index page in the 'Buddhist theory' section.)

This week we're taking a look at the eighth factor of the path, right concentration. In the quotation above, the Buddha explains right concentration as the practice of the four jhanas - altered states of consciousness which we can train ourselves to enter through diligent practice. I've written about jhana several times before (giving detailed instructions here, setting the jhanas in the context of the wider path here, and looking at the so-called 'higher' or 'formless' jhanas here), so rather than repeat that material here, I'll instead try to give a sense of my current understanding of what the jhanas actually are, what function they serve in the context of the Eightfold Path, and then take a look at how some other traditions have arrived at different solutions to the same problems. What actually are the jhanas anyway? The jhanas are altered states of consciousness that can be entered through meditation. Each has a number of associated 'factors', but at a high level, the first jhana is a state of strong bodily bliss, the second jhana is a state of strong emotional joy or happiness, the third jhana is a state of quiet contentment, and the fourth jhana is a state of deep peace and equanimity. (I go into much more detail about the jhana factors here.) The jhanas are sometimes described as 'concentration states', and they're strongly associated with samadhi practice, often called 'concentration meditation'. The basic idea with samadhi practice is to rest your attention on an object, and when you notice that your mind has wandered, let go of the distraction, relax, and come back to the object. Rinse and repeat until the mind wanders less and less - there's often a kind of tipping point when you notice that you aren't really getting distracted any more (a state which my teacher Leigh Brasington would call 'access concentration'). Following the instructions from this article, you can then enter the first jhana - at least, the way Leigh and I teach it. It turns out that this is not the only interpretation of jhana. Some teachers require a much, much deeper level of concentration than what's described above before they're willing to call the resulting state 'jhana' - see the work of teachers like Pa Auk Sayadaw, Tina Rasmussen and Beth Upton for examples. And other teachers require less concentration, such as Bhante Vimalaramsi, because they want to use their version of the jhanas to do things that are difficult to do when the mind is more deeply concentrated. And to cap it all, every teacher worth their salt will tell you that their version of the jhanas is what the Buddha really taught, accept no imitations! What's a meditator to do? My impression now, after ten years of jhana practice in Leigh's style and having dabbled a bit with a few other approaches (both a bit lighter and a bit deeper - I haven't gone really deep, so if you'll only accept the deepest of the deep, you can stop reading now!), is that it isn't really accurate to call the jhanas 'concentration states'. I say that because I can enter an altered state of consciousness which is recognisably one of the jhanas at will, without having first done the preparatory practice to stabilise my mind and build up concentration. The resulting state is weak, unclear and easily lost, but is still clearly whichever jhana I was aiming for - it's the same state, just with substantially less concentration. If I build up more concentration first, I go into a version of the jhana which looks exactly like what Leigh taught me. If I build up even more concentration first, the phenomenology starts to resemble some of the deeper jhanas taught by other teachers. And I presume that if I built up incredibly strong concentration, I would end up in the version of the jhanas taught by Pa Auk and friends. So if the jhanas aren't 'concentration states', why do they come under the heading of 'right concentration', and why are they taught on 'concentration retreats'? Well, for one, it's very helpful to have a concentrated mind to learn the jhanas in the first place. When you're first learning the practice, you're asking your mind to go somewhere unfamiliar, and that's a difficult thing to do. It's very helpful to have stabilised the mind beforehand so that it's less prone to wandering - otherwise you'll probably fall out of the state before you've had a chance to get used to it. Once you've become more familiar with the jhana, you'll probably find that you can intuitively 'incline' your mind toward it, and enter the jhana with less concentration than it took when you were first learning. Secondly, and more relevantly for the Eightfold Path, the jhanas are also a fabulous way to deepen your concentration. Fundamentally, the jhanas are states of enhanced wellbeing - they're nice states that the mind likes to inhabit. Bliss, joy, contentment, peace - these are good places to be, so once the mind figures out how to find them, it gets easier to stay there for long periods. While you're in the jhana, you're focused on the qualities of the jhana itself, and so the mind will tend to be even less prone to distraction than it was previously, and thus become more deeply concentrated. The stillness and clarity of the mind coming out of the fourth jhana is typically much stronger than the stillness and clarity of a mind which has spent the same length of time in access concentration. So concentration helps us to find the jhanas in the first place, and then in turn the jhanas help us to deepen our concentration further. That sounds like a solid definition of 'right concentration' to me. Other interpretations of right concentration As I mentioned above, some teachers have extremely high standards for jhana - high enough that most people don't have the time or even the capacity to develop concentration deep enough to meet their requirements. Perhaps as a result, you'll now find many teachers who will say that jhana isn't necessary at all, or even that it's a bad idea - just another cause for attachment. (To that I would say - can you get attached to the jhanas and start using them just to get high? Sure. Don't do that. There are lots of ways to misuse spiritual practice, but that doesn't mean you should reject the whole thing. That's like saying that because you might burn yourself on a flame, everyone should eat all their food raw all the time to avoid the terrible risk of getting burned. Raw food is fine if that's what you're into, but you could alternatively learn not to burn yourself and then enjoy cooked food. To each their own.) At the extreme end of the spectrum, you'll find teachers offering what's usually called 'dry insight'. This approach doesn't have any 'concentration practice' per se - students will simply go directly into an ***insight practice. (See, for example, Mahasi noting.) But now these teachers have a problem, because 'right concentration' is one of the aspects of the Eightfold Path, and they've deleted the concentration practice. Their solution is to emphasise 'momentary concentration', or 'khanika samadhi'. This is the type of concentration needed to stay focused on a complex, moving task - such as noting the arising and/or passing away of every sensation in your sensory experience. By comparison, the type of concentration I described above - putting your attention on one object and staying with it for a prolonged period - can be called 'one-pointed samadhi'. The noting practice is not one-pointed - since you're moving your attention from one sensation to another in order to note it - but you do nevertheless stay engaged in the (moving) practice for an extended period of time, so there's a kind of 'concentration' there. The 'momentary concentration' approach has a couple of advantages. First, it's simpler - you only have one type of practice to do (your insight practice), rather than two. Second, some people have a really hard time focusing the mind, and so find one-pointed samadhi practice to be pretty unbearable. Being given permission to 'skip' the concentration can actually be really helpful in a circumstance like that, because it allows the practitioner to focus on their strengths rather than having to suffer through their weaknesses. Another, more middle-ground, approach to redefining 'right concentration' is to make some effort to develop one-pointed concentration, but to omit any mention of jhana. (See, for example, the concentration practice in the Goenka tradition, which builds one-pointed concentration on the breath without referencing jhana at all.) Again, this has some advantages. Most practitioners will develop more concentration this way than through the 'dry insight' route, which will in turn make their insight practice deeper and more impactful. And by omitting any mention of jhanas, there's no need to learn altered states of consciousness which - depending on whose definition you're using - may be difficult or even unattainable. Needless to say, I'm a fan of the jhanas! They really helped me, and I've seen them help plenty of other people too. But I've also seen people do well in other styles of practice too, so - despite the quotation at the top of the article - I don't want to give the impression that I think you'll go straight to Buddhist hell if you don't learn the jhanas right away. (Even so, I'd encourage you to give them a try! Come on a retreat with Leigh or me and see what happens. I'm currently hoping to arrange some retreats in Europe over the next few years, and I'd like some people to come to them - maybe you could help me out here?) What does Zen make of all this? Amusingly enough, although the words 'Zen' and 'jhana' actually come from the same root (Pali 'jhana' -> Sanskrit 'dhyana' -> Chinese 'chan'na', shortened to 'chan' -> Japanese 'zen'), the Zen tradition tends not to teach the jhanas, at least not openly. It's actually very common for meditators of all traditions to stumble into the jhanas - I recently met a guy who said he was interested in them but had no idea how to get there, and when I asked him about his practice it was clear that he'd been in at least the first jhana many times without recognising it. In the case of Zen, though, the teacher will typically show little interest in reports of altered states of consciousness, saying something like 'Oh yes, that happens from time to time, just let it come and go like everything else.' Within the Soto tradition there's a much greater emphasis on 'ordinariness' and integration into daily life, while Rinzai Zennies are usually more interested in insight, kensho and satori than altered states which are not themselves intrinsically insight-producing. (Another risk of jhana is that people might mistake them for insights, because 'look, something's happening!' - again, in my mind, that's an argument in favour of teaching the jhanas openly, so that practitioners know what's happening, rather than concealing or demonising them, but whatever.) As far as Zen is concerned, though, it's also worth noting that there's perhaps a little less need for a jhana practice in that context than in the early Buddhist context. Many of the insight practices in early Buddhism (and the Theravada tradition that developed out of it) place great emphasis on noticing impermanence and unreliability - and it can be unsettling or even destabilising to notice these things directly. Spending time cultivating the jhanas sharpens the mind, allowing you to notice impermanence more easily, but also stabilises it, allowing you to face aspects of your experience which would be unnerving or upsetting under normal circumstances, but which are easier to bear with the equanimity cultivated through samadhi. So you end up with two practices: samadhi to stabilise the mind, then insight which unsettles it, then back to samadhi to restore the stability, then back to insight to keep digging deeper, and so on. By comparison, Zen's two major practices are Silent Illumination and working with a koan. Silent Illumination can actually be defined as a balance of stillness (the silence, aka samadhi) and clarity (the illumination, aka insight). We stabilise our attention on the totality of the present moment and allow it to reveal itself to us more and more deeply - we aren't particularly focusing on impermanence or unreliability, or deconstructing anything, we're not actually doing anything apart from simply remaining aware. Individual moments of insight may have a destabilising effect, but the practice itself doesn't have an intrinsically abrading effect on the mind's calmness - quite the opposite. Working with a koan can be a bumpier process, especially at first, when asking the question is bringing up all kinds of thoughts and ideas. But the key is that we don't do anything with whatever comes up - we simply notice it, let it go, and then ask the question again. Over time this has a kind of 'winnowing' effect, ultimately allowing the mind to become focused on the questioning itself rather than whatever 'answers' might be coming up. This focus on 'wanting to know' (sometimes called Great Doubt in the Zen tradition) should be balanced with a kind of radical openness, a willingness to receive an answer in any form, from any direction, at any moment. Thus, again, we have a balance of stillness (the focus on the questioning) and clarity (the receptivity to whatever may come up) - incorporating both 'concentration' and 'insight' into one practice. So what exactly is 'right concentration'? Well, if you're a purist, and you want to go with what the Buddha is reported to have said in the Pali Canon, then click on the link at the top of this article and check out Samyutta Nikaya 45.8 - and you'll find right concentration defined in terms of the four jhanas. You can use the resources on this website, or buy Leigh Brasington's excellent book Right Concentration, or (best of all) come on a retreat with Leigh or me and give it a go. (In fact, you can do any of those things even if you aren't a purist!) If you're more inclined to the Zen way of things, then the key is to ensure that your practice includes both aspects - the silence and the illumination, the questioning and the receptivity. More generally, any amount of concentration, of any sort, is likely to strengthen your insight practice - so even if you aren't interested in jhana, it's worth taking a look at how concentration might manifest itself in your practice. It's in the Eightfold Path for a reason! The end of the Eightfold Path? So, this brings us to the end of this article, and this series. Like I said at the start, though, the Eightfold Path isn't really sequential - you don't start with right view or end with right concentration. All eight aspects are to be practised as part of one holistic path. Different aspects will come to the fore at different times - but they're all helpful in their own ways. It can be interesting to reflect on this from time to time - are there aspects of the path where you're stronger, aspects which don't get so much attention? What might happen if you spent some time focusing on a neglected aspect of the path? And what does each aspect mean to you - not just in terms of the 'textbook' definition, but as an actual, living practice? How might the Eightfold Path manifest itself in your life? Finding a way forward when none of your options are viable