A practice guide for the teachings of Zen master Bankei

As noted in my previous blog, my life circumstances have taken a turn which means that I have less time and energy available for face-to-face teaching right now. But that doesn't mean I've given up! For the last few months, I've been hard at work on a book, which I'm pleased to say has now been released.

The book, Resting in the Unborn, is a practice guide for the teachings of the enigmatic Zen master Bankei, whose awareness-based approach to awakening is so profoundly simple that it can at times seem totally unapproachable. My hope is that the book will bridge the gap for people (like myself!) who find his teachings inspiring, but aren't quite sure what to do with them. You can find out more about the book on the corresponding page on my website, but it's offered freely, so you've nothing to lose by downloading it and jumping in right now! If you'd prefer a print copy, that's also available via the Lulu store; there's a small cost for that, which covers the expenses of printing and shipping the book. I really enjoyed writing this book. It brought me face to face with the strengths and weaknesses of my personal practice, highlighted areas where I really needed to look more closely at what's going on, and inspired me to keep going on the path that has proven so rewarding over the years. I hope it's of some benefit to you as well.

0 Comments

Taking some time to rechargeChristmas is almost upon us! It's a time to reflect on the year that's now been and gone, to spend time unwinding and recharging, and perhaps to make some plans for the year ahead.

In my case, that reflection has led to some difficult decisions. I've been running a weekly class for over five years now, and for the last three of those years I've also been publishing an article in this section of the website every week, with the result that there's now over 150 of the things - probably more than anyone will ever want to read! Teaching and sharing in this way has been hugely rewarding and fun, and the class in particular has introduced me to some wonderful people. But it's also taken a toll on me, and I've become more and more aware of my own limitations in terms of how much I can continue to give week after week. It's reached a point where I need to make a change - I need some time for self-care, to recharge my batteries and nourish my own practice. I also need to build some space into my weekly routine to look after my Mum, who isn't doing so well at the moment - I need to be able to drop everything at short notice to visit her (I live three hours away) without worrying about when my class planning is going to get done. (I'm writing this article at my Mum's house after spending most of the day at a local hospital. She's OK but has a long road of recovery ahead.) As a result, I've decided to pause Wednesday night class, and thus the articles in this section of the website, for at least six months. I'm hoping that that will give me some time to navigate through my current situation and recover some equilibrium. I'm sorry if this is disappointing for you, but at this point I've tried quite a few ways to mitigate the impact of running the class, and taking a break seems like the right move now. I'm very grateful to everyone who's attended my class and read these articles over the years, and I hope you feel it's been valuable too. All the material posted here will remain available, including a complete commentary on the koans in the Gateless Barrier, and practice guides for the Satipatthana Sutta and Anapanasati Sutta. I hope that these small contributions to the Dharma world continue to be of value. I may also continue to add new material from time to time as the mood takes me, but the weekly feed of articles will stop for now. I fully intend to meet all other existing teaching commitments in 2024 - the Silent Illumination day retreat in January, the online Contemplation course with Leigh Brasington in February, and the Jhana retreat with Leigh in November/December. I'm also very open to exploring other vehicles for teaching which aren't quite so draining - perhaps events, short courses, etc. - although I don't have any concrete plans yet. If and when I do, you'll be the first to know! Thank you again for reading these articles, and I wish you all the best with your practice. As ever, please feel free to get in touch if you have questions. May all beings be free from suffering and the causes of suffering. Bringing the Anapanasati Sutta togetherOver the past few weeks, we've been looking at Majjhima Nikaya 118, the Anapanasati Sutta - the discourse on mindfulness of breathing in and out.

The Anapanasati Sutta presents a practice composed of sixteen steps, grouped into four 'tetrads' - four groups of four steps each - and in past weeks we've taken each tetrad in turn:

This week it's my last article (and class) of the year, so it seems fitting to bring it all together into a single unified practice. Before we get into that, though, I think it's also worth saying a few words about how we might choose to approach such a detailed, complex practice, since at first sight it can appear a bit daunting, especially compared to much simpler practices like Silent Illumination. A high-level outline of the Anapanasati practices Anapanasati provides us with a flexible, self-contained approach to practice that covers two of the major bases of early Buddhist practice - developing samadhi (calming, focusing and unifying the mind) and cultivating wisdom (liberating insight into the nature of reality). If we're interested in heart-opening practices or the jhanas, there are places where those can optionally be accommodated into the Anapanasati scheme as well. The practice begins with the preliminaries - finding a place to meditate where you won't be disturbed, setting up a reasonably comfortable and sustainable posture that allows you to feel relaxed but alert at the same time, neither tense nor falling asleep. Then, as the foundation for the practice, we begin by paying attention to the sensations of the breathing. Like a number of other schemes of practice (such as the way I teach Silent Illumination in class), Anapanasati assumes that we will be coming to our practice with a comparatively 'busy' mind which wanders frequently. When the mind is busy, it's helpful to start with a meditation practice that's also 'busy' - if we try to start with a practice that's too quiet and subtle, it's very likely to come across as 'boring', and the mind will refuse point-blank to focus on it. If, instead, we start with something a bit more engaging, our minds are more likely to settle into the practice. Then we can begin to move the meditation practice in a subtler direction, and our minds will become quieter and subtler along with it. So Anapanasati starts with paying attention to the breathing in a fairly simple, coarse manner. For some of us, that's still too subtle, so it can help to count the breathing, incorporate a mantra in time with the breath, or add a visualisation of an ocean wave going in and out as you breathe. A few minutes with an aid can help a particularly rambunctious mind to settle down enough that you can drop the aid and simply rest with the breathing. It's important to say that you don't need to have 'perfect' focus before moving on! You're looking for a helpful reduction in mind-wandering. If 99% of your 'meditation time' is spent thinking about something unrelated, then not much is going to happen, but if you can get it to the point where you're with the practice more often than not, you're in a decent place. I encourage you to experiment for yourself to figure out what's useful and what isn't - just bear in mind that trying to attain 'perfection' is setting yourself up to fail. The mind wanders, and it doesn't help to demonise that. When we've established a basic, good-enough level of focus, we move into the first tetrad, which concentrates on refining our awareness of the body sensations, culminating in allowing the body to become so still and quiet that subtler sensations start to become apparent. We then move through the second tetrad, to progressively subtler aspects of experience - subtle body sensations and then purely mental qualities. Eventually, our mental activity settles down in the same way that the bodily activity settled in the previous step. When both bodily and mental activity have settled to some degree and become less distracting, we're then able to turn the attention more easily to the mind, or awareness, itself. Here, in the third tetrad, the settling process can go even deeper, resulting in a mind which is greatly less prone to distraction than it was at the start. (This is the point where we can introduce jhana or Brahmavihara practice, if we can do so in a way that deepens our focus rather than disturbing it - see the discussion in the article on the third tetrad for more details.) Finally, we have a mind which is razor-sharp and well prepared for insight practice, which is the subject matter of the fourth tetrad. The final steps lead us through a careful examination of impermanence, ultimately culminating in the deep letting go which is the ultimate goal of all spiritual practice. Three ways of working with Anapanasati We've been exploring the Anapanasati practice in my Wednesday night class over the last few weeks, taking one tetrad each week. We had about 30 minutes for practice time each week, so we would start with 6 minutes of 'plain' mindfulness of breathing, then spend 6 minutes on each step of whichever tetrad we were looking at that week, with me watching the clock and calling the changes. As a way of dipping a toe into each of the sixteen steps and getting a very basic sense of how the practice works, this is fine, but moving through the steps 'on the clock' might not be the best way to approach it. (If you're going to do this, at least set up a timer to ring a bell each time you're moving on to the next step, so that you aren't practising with one eye on the time all the way through - that's generally very unhelpful.) Here are three alternative ways to approach the practices in this discourse. Note that the first two of these require you to have a fair chunk of practice time available, so might be better suited to retreat-style practice (or a weekend when you haven't got much on), but experiment for yourself to see what works. At the end of the day, it's your practice not mine, and if you find something of value in here then you don't need my approval!

Perhaps the most natural way (at least to me) to approach this discourse is to start at the beginning and move through each step sequentially when the mind feels ready to do so. So you start by paying attention to the breath, then when the mind is starting to feel a bit more settled and focused, introduce an awareness of the lengths of the breath (steps 1 and 2) to refine the subtlety of your awareness. Often, tweaking the technique will lead to increased distraction at first, as the mind tries to take on board something new, but stay with it - after a while, things will settle down again, and now you'll be more focused than you were previously. When it feels like you've reached a good level of stability, move on to step 3, broadening out the scope of awareness to include the whole body - and so on. Stay with each step until you have a sense that it's 'good enough' to move on. What's 'good enough'? That's something you'll have to figure out for yourself. In general, the more settled and stable the mind, the easier the next step will be and the deeper the practice will go, but there's also a point of diminishing returns where you start to run out of energy and eventually the practice stops working entirely. The more you do it, the more your mind will be able to 'find its way back' to each of the steps, so you'll tend to find you can progress more quickly - but sometimes you might have the opposite experience, and end up spending all of your practice time at the earlier stages. Sometimes you might even feel the need to go back a step or two, if you realise you've moved too fast and the stability isn't there. Other times you might actually skip a step that's giving you trouble if you know you can get something out of a subsequent step. The point here is not to find a single, prescriptive pace at which to move through the sixteen steps, but instead to develop an intuitive relationship with your own mind through the vehicle of the sixteen steps.

An approach I never would have considered myself if I hadn't read it in Bhikkhu Analayo's book is to run 'quickly' through all sixteen steps as a kind of diagnostic, noticing if any steps in particular jump out at you, then returning to those steps for the bulk of your practice time. This approach reminds me of one of the ways of working with the Five Daily Reflections, where you say each of the five out loud in turn, then choose whichever one seems to have the most importance for you right now. Sometimes, there's a particular point that really demands our attention, and it can be more fruitful to spend the bulk of our practice time there rather than going through the motions of everything else just for the sake of completionism. So, in the Anapanasati case, doing a quick run through all sixteen steps may 'highlight' a particular area worthy of deeper contemplation. Of course, sixteen steps is a lot, and even running through them 'quickly' can take up a lot of time! (I have the sense that Bhikkhu Analayo would look at my typical daily practice as more of a warm-up before starting the real work...) Still, it's an interesting idea - give it a try sometime and see what happens.

In effect, this approach is what we've been doing over the last four weeks, taking one tetrad at a time and focusing just on that. (There's evidence that this happened in the Buddha's time as well - several discourses include only the first tetrad of Anapanasati, for example.) Going further, you don't even have to limit yourself to picking one tetrad. You could instead treat the Anapanasati Sutta as a kind of anthology of practices (which is how we work with the Satipatthana Sutta), and simply pick and choose whatever seems interesting. It's a good idea to include some amount of insight practice, even if you're much more drawn to the samadhi side. Settling and focusing the mind can feel really good, but if that's all you do, it can lead to some problems. People sometimes space out or withdraw, using the practice to avoid dealing with uncomfortable or unpleasant aspects of their lives. I can relate to this - yesterday evening, as I was on my way home from work, a group of youths threatened me and threw something at my house, and right now I'm feeling a strong pull to withdraw from the world and shut myself up in a safe place where I don't have to deal with anyone. That isn't a good long-term strategy, though! Sooner or later I have to get back out there so that my life can function as usual. Getting back on topic, the major drawback with samadhi practice is exactly this - it can lead to a kind of withdrawal into a comfortable, isolated space, a 'happy place' that we can retreat to more and more, even if the rest of our life is disintegrating around us. Insight practice has a way of challenging that kind of isolationism, confronting us with what's really going on, warts and all. Ultimately, the two - samadhi and insight - work best hand-in-hand. Samadhi gives us joy, peace and equanimity, providing us with a stable base from which to explore our insight practice. Insight opens us up to the world around us, and ultimately leads to deeper and more long-term liberation than simply cultivating the temporary 'happy place' of samadhi, but it can also sometimes be unsettling, particularly when we realise the extent to which we've been unconsciously concealing the undesirable aspects of reality from ourselves. Also, those insights will tend to touch us more deeply - resulting in greater wisdom - if our minds are more focused and more opened up as a result of a samadhi practice. So by all means approach the Anapanasati practice with a creative, non-linear approach - experiment with different combinations, play to your heart's content - but I would very much recommend trying to ensure that you incorporate elements of both samadhi and insight into your practice. It'll be stronger in the long run. Anapanasati practice instructions summary Without further ado, let's review the complete practice of Anapanasati. Sections in italics are taken from the discourse; everything else is my commentary.

Here, gone to the forest or to the root of a tree or to an empty hut, one sits down; having folded one's legs crosswise, set one's body erect, and established mindfulness in front of oneself, ever mindful one breathes in, mindful one breathes out. Find a space where you won't be disturbed for the duration of your practice. Set up a comfortable, sustainable posture, relaxed and alert. Bring your attention to your breathing. Feel the sensations of in-breath and out-breath. Find a particular place in the body where you can follow the sensations, rather than moving around too much. Continue to focus on this place in the body during the gaps between each breath.

Breathing in long, one understands: 'I breathe in long'; or breathing out long, one understands: 'I breathe out long.' Breathing in short, one understands: 'I breathe in short'; or breathing out short, one understands: 'I breathe out short.' Continuing to follow the breath, begin to notice the comparative lengths of each breath. Is this in-breath shorter or longer than the previous out-breath? What about the previous in-breath? Are your breaths all roughly the same length, or is it more variable?

One trains thus: 'I shall breathe in experiencing the whole body'; one trains thus: 'I shall breathe out experiencing the whole body.' Maintain your awareness of the breath, but now allow your awareness to expand to encompass the whole body, so that your breathing is the focal point but your peripheral awareness includes the sensations from the rest of the body as well. Find a balance where you can maintain both this broader, more open awareness of the body as a whole and the sense of the breathing as being 'highlighted' within that wider field of sensation.

One trains thus: 'I shall breathe in calming bodily activity'; one trains thus: 'I shall breathe out calming bodily activity.' Maintain your awareness of breath and body. Notice that, as you continue to rest in this awareness, your breath and body begin to relax and calm down, without you having to do anything deliberate to make that happen. Simply hold the intention to allow that process of calming to continue.

One trains thus: 'I shall breathe in experiencing joy/rapture [piti]'; one trains thus: 'I shall breathe out experiencing joy/rapture [piti].' Maintain your awareness of breath and body, but pay particular attention to the pleasant physical sensations in your field of experience. As the body calms and relaxes, these might take the form of subtle/energetic body sensations rather than coarse/physical body sensations. Allow yourself to enjoy these pleasant sensations whilst maintaining your awareness of the breathing. By the point, the awareness of breathing may have receded to the 'background' while your awareness of pleasant sensations is in the foreground, but the breathing should never be lost altogether.

One trains thus: 'I shall breathe in experiencing happiness/pleasure [sukha]; one trains thus: 'I shall breathe out experiencing happiness/pleasure [sukha].' Maintaining a background awareness of the breathing, now pay particular attention to pleasant emotional sensations. For example, you might notice that it feels pretty good to have a calm body and a focused mind - recognise that quality of contentment, happiness or even joy, and allow yourself to appreciate or enjoy it.

One trains thus: 'I shall breathe in experiencing mental activity [citta sankhara]'; one trains thus: 'I shall breathe out experiencing mental activity [citta sankhara].' Maintaining a background awareness of the breathing, widen the scope of your awareness beyond positive emotions to include all mental activity - thoughts, mental images, emotions. Maintain a gentle, broad awareness of your mental activity as a whole, noticing it without getting involved.

One trains thus: 'I shall breathe in tranquillising mental activity [citta sankhara]'; one trains thus: 'I shall breathe out tranquillising mental activity [citta sankhara].' Continue to maintain your awareness of both the breathing and your mental activity. Notice that, as you continue to rest in this uninvolved awareness of your mental activity, that activity begins to slow down and settle, without you having to do anything deliberate to make that happen. Simply hold the intention to allow that process of calming to continue.

One trains thus: 'I shall breathe in experiencing the mind'; one trains thus: 'I shall breathe out experiencing the mind.' Maintain your awareness of your breathing, and notice that you are aware of your breathing - become aware of your awareness itself. If this is difficult, you might alternatively experience 'awareness of awareness' as a sense of finding a 'still point' at the centre of your awareness; or it might help to become aware of the totality of your experience 'as one thing', then focus on the 'one thing' rather than the 'contents' of awareness. (More on this tricky point in the relevant article.) However you find it, continue to maintain an awareness of your breathing in the background, whilst focusing on awareness of awareness in the foreground.

One trains thus: 'I shall breathe in gladdening the mind'; one trains thus: 'I shall breathe out gladdening the mind.' Continue to maintain awareness of the breath and awareness of awareness. Notice that there's a kind of inherently pleasant quality to resting in awareness of awareness - a subtle contentment which is not dependent on any particular content of awareness, but intrinsic to the act of simply being aware. Allow that subtle contentment to permeate your practice.

One trains thus: 'I shall breathe in concentrating the mind'; one trains thus: 'I shall breathe out concentrating the mind.' Continue to maintain awareness of the breath and the awareness of awareness. Notice that, as you continue to rest in this subtly pleasant experience, your mind becomes even more settled and less prone to distraction, without you having to do anything deliberate to make that happen. Simply hold the intention to allow that process of settling to continue.

One trains thus: 'I shall breathe in liberating the mind'; one trains thus: 'I shall breathe out liberating the mind.' Continue to maintain awareness of the breath and the awareness of awareness, allowing the mind to become even more fully free from distraction, liberated from the usual mental hindrances that can pull us out of our meditation practice. If you have a jhana practice, you can include it here to deepen the mind's stability and gladness still further. Likewise, if you have a Brahmavihara practice and you can connect with it without introducing a lot of mental activity (i.e. without using phrases or visualisations), you can include it here to deepen the mind's stability and gladness still further.

One trains thus: 'I shall breathe in contemplating impermanence'; one trains thus: 'I shall breathe out contemplating impermanence.' Bring your attention fully back to the breathing. Notice that each breath is not just 'one long sensation' - each breath has a beginning, middle and end, which are different from each other. As you look more closely, notice that the 'beginning', 'middle' and 'end' are also composed of smaller 'parts', a collection of sub-sensations which likewise come and go. Continue to explore the sensations of the breathing, noticing the impermanence that you find at every level of the breathing. If the mind wanders, notice that this too is impermanent - both the distraction itself (whether it's a thought, a sound or something else) and the attention that we give to that distraction have a beginning, middle and end. Indeed, whatever arises within our experience - sights, sounds, thoughts, feelings, sensations - has the same nature of impermanence, the same qualities of arising, duration, cessation.

One trains thus: 'I shall breathe in contemplating dispassion/fading away'; one trains thus: 'I shall breathe out contemplating dispassion/fading away.' Maintaining your awareness of the breathing, focus particularly on the 'second half' of each breath. Notice that every sensation has the nature to fade away - it's impossible to hold on to anything, even if we wanted to. As we connect with this sense of fading away, we may start to perceive clearly the futility of the clinging which gives rise to our experience of suffering, and thus experience 'dispassion' (a fading or reduction of suffering).

One trains thus: 'I shall breathe in contemplating cessation'; one trains thus: 'I shall breathe out contemplating cessation.' Maintaining your awareness of the breathing, focus particularly on the moment when each sensation ceases. (If it helps, you can introduce the mental label 'gone' each time you notice a sensation vanish.) The mind is typically drawn to arising rather than cessation - you might also notice how each arising is inevitably bound up with a cessation, as your attention shifts from the previous (now gone) sensation to the new one. We may encounter resistance at first when turning our attention toward cessation, but in time the mind begins to let go even more deeply, perceiving a world of vanishing in every direction.

One trains thus: 'I shall breathe in contemplating letting go'; one trains thus: 'I shall breathe out contemplating letting go.' At this stage, no instructions are necessary or useful. Ultimately, the purpose of the method is to take us to a place where the method can be put down, and we allow ourselves simply to let go into the flow of experience, moment by moment. Final words It's been a pleasure and a privilege to explore this discourse with you over the last few weeks. Of course, five weeks barely scratches the surface of a profound practice like this one - Anapanasati could easily provide us with a framework for life if we're so inclined. I've certainly come away from the experience with a profound respect for this frankly ingenious system of practice! If you'd like to study Anapanasati in more detail, I'd recommend Bhikkhu Analayo's book on the topic. Another approach is described by Ajahn Buddhadasa in his own book on the subject. Plenty of teachers out there are specialists in Anapanasati (which I'm definitely not), so if this is a practice you'd like to take further, it's well worth seeking them out. I wish you well on your Anapanasati journey! Letting go into the flow of lifeThis week we're continuing once again with our discussion of the Anapanasati Sutta, looking at the fourth and final section (or 'tetrad') of practices, before bringing it all together next week in the final article of the year. Each step in the Anapanasati Sutta builds on the ones that came before it, so there will be a few references back to the previous parts (part 1, part 2, part 3) - it may be worth reading those first before proceeding unless you're already familiar with this discourse.

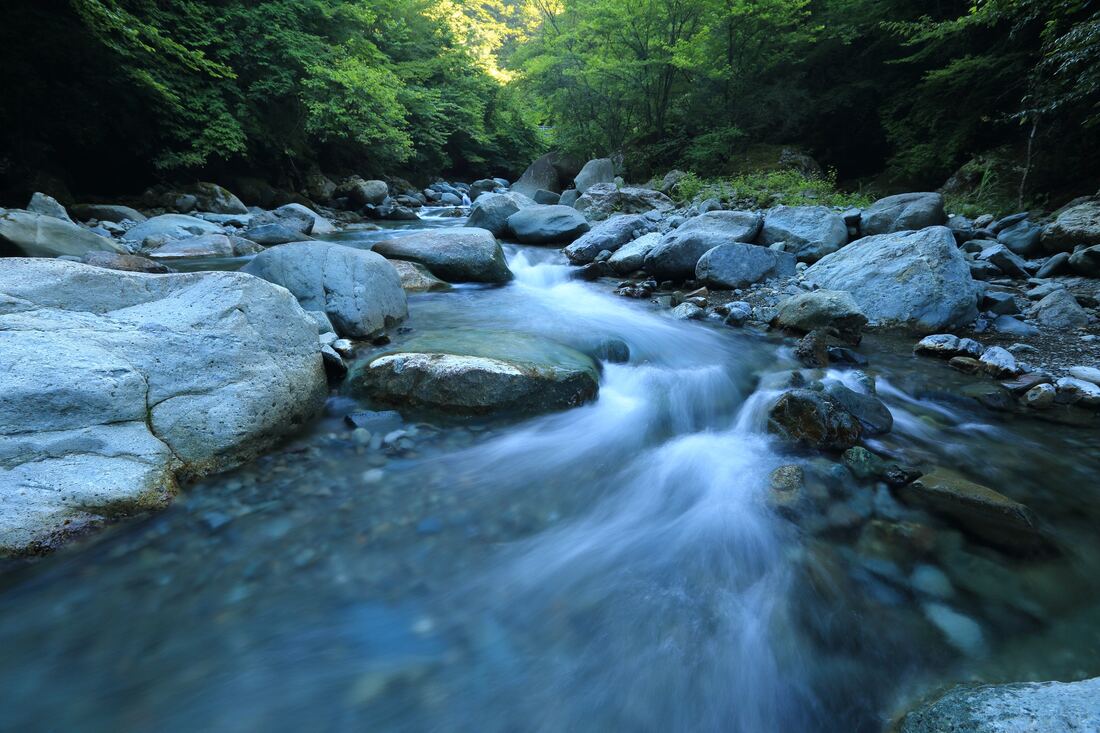

Without further ado, let's get into the Buddha's instructions for the final four steps of this practice! The fourth tetrad, in the Buddha's words One trains thus: 'I shall breathe in contemplating impermanence'; one trains thus: 'I shall breathe out contemplating impermanence.' One trains thus: 'I shall breathe in contemplating dispassion'; one trains thus: 'I shall breathe out contemplating dispassion.' One trains thus: 'I shall breathe in contemplating cessation'; one trains thus: 'I shall breathe out contemplating cessation.' One trains thus: 'I shall breathe in contemplating letting go'; one trains thus: 'I shall breathe out contemplating letting go.' The fourth tetrad is associated with 'mindfulness of dhammas', which essentially means bringing mindfulness to the deeper aspects of the Buddha's teaching, and in the case of the Anapanasati Sutta signals a pivot away from the samadhi orientation of the previous three tetrads (steps 1-12) and toward a greater focus on insight practice for the final four steps. As with each previous tetrad, we continue to use mindfulness of breathing as the 'foundation' of our practice - the constant thread running through all sixteen steps. If we ever find that we're no longer aware of our breathing, that's a sure sign that the mind has wandered, and it's time to renew our intention. As I mentioned last week, if we've been following the first 12 steps up to this point, our minds are likely to be pretty calm and focused by this stage, so we probably won't lose the breath that often. If we jump straight in at step 13 - an approach often called 'dry insight' - then there's likely to be a lot more mind-wandering. The practice will still work, but it's likely to be less efficient and impactful than it would be if we'd spent some time stabilising the mind first. But if, for whatever reason, you just want to go straight for the insight practices without the preceding samadhi component, you can board the anapanasati train at station 13: contemplation of impermanence. Step 13: Impermanence 'Impermanence' is one of those big Buddhist concepts that it's easy to get a very quick intellectual handle on. Everything changes, right? The only constant is change itself. Civilisations rise and fall. The sun rises and sets. The seasons cycle on. (At the time of writing, winter has recently arrived here, and it's gone from being rather brisk outside to positively freezing. Change is also apparent in my wardrobe - the gloves, hat and scarf have now made their annual reappearance.) But, well... So what? Yeah, we get it, things change. Who cares? What's supposed to be insightful about that? From a Buddhist perspective, the contemplation of impermanence helps to undermine our own minds' tendency to want to solidify things. When we meet a person, we form a kind of mental 'snapshot' of who they are - they like xyz, they don't like abc, they do these sorts of things, and so on. If, the next time we meet that person, they're doing something wildly different, it's a confusing experience - this person is exhibiting behaviour that doesn't align with our snapshot of them, which means that either we have to update our snapshot or explain it another way (oh, he was only saying that because he was drunk, that's not who he really is). The truth is that everything is changing all the time, and life goes easier for us if we're able to open ourselves fully to that truth. It means that our minds can't use quite so much shorthand to simplify everything, but it has the advantage that the world appears fresher, newer and more interesting - and, critically, that we aren't caught off guard so much when something changes that we secretly believed should have been totally dependable for all time. One way to open ourselves up to impermanence is to pay attention to the changing nature of our experience in meditation. For example, when we breathe, things are changing all the time. The in-breath has a beginning, a middle, and an end. Then there's a gap. Next comes the out-breath, which also has a beginning, a middle and an end. Then there's another gap. Next is another in-breath - different from the previous one, if we're really paying attention. Maybe it's a bit longer or a bit shorter, maybe we feel the sensations in a slightly different part of the body - perhaps the left side of the nostril is more noticeable than the right side for one breath, then it's the other way around next time. And so on. You can tell that this is working when the breath becomes interesting. At first, it really isn't. You breathe in, you breathe out, you breathe in again - yep, got it, what's next? When we relate to the breath on this conceptual kind of level - 'breathing in now', 'breathing out now' - there's not a lot going on, and so the mind wanders very easily and the practice is dull as ditchwater. But when you connect with the impermanence - the flowing quality of each breath - then each moment is new and distinctive in its own way, and the practice becomes much more like watching a flowing river which is a little bit different every single moment. When you've got a taste for that, we move on to... Step 14: Dispassion / fading away Dispassion is Bhikkhu Analayo's translation; Bhikkhu Bodhi prefers 'fading away'. At first glance these look pretty different, so what's going on? These days, when we talk about 'passion' we typically picture some kind of torrid love affair, or someone who wears their emotions on their sleeve. With that interpretation in mind, 'dispassion' can sound a bit rubbish - like we're going to become an emotionless zombie incapable of feeling love. Yikes. But the original meaning of the term 'passion' is actually 'suffering' - you might have come across the term 'the Passion of the Christ', in relation to the story of Jesus's crucifixion. So, in a Buddhist context, 'dispassion' is ultimately about suffering less. How do we become dispassionate, then? Well, first we have to recognise what causes us to suffer - and, if the Buddha's Second Noble Truth is to be believed, it's our attachment to desire - desire for sense pleasure, desire to become something attractive, desire to get rid of something unattractive. A traditional remedy for such desires is to contemplate their unsatisfactory nature - and, building on the previous step, one way to do that is to recognise their impermanence. Yes, it's nice to have nice things, but sooner or later those nice things will come to an end - will 'fade away', as Bhikkhu Bodhi has it. In practice terms, we might thus shift our attention primarily to the latter half of each breath, noticing that whatever has arisen is subject to passing away. (In the early discourses, a common indication that one of the Buddha's followers has reached the first stage of awakening is that they exclaim 'All that is subject to arising is subject to passing away!' - so this is well worth exploring until your experiential appreciation of impermanence goes bone-deep.) Ultimately, we can thus become aware of the transient nature of everything in our lives. Continuing the river analogy from the previous step (borrowed from Bhikkhu Analayo's book on the Anapanasati Sutta!), it's as if we're now standing on a bridge over the river and watching the water moving away from us. Perhaps we see small twigs and other objects floating along the river; they're here for a while, but the river is carrying them inexorably away from us, so there's no use in getting too attached to them. This, too, shall pass. Again, when we have a clear sense of fading away and the dispassion that comes with it, we move on to... Step 15: Cessation There's a particular power in trying to notice the moment that an experience ends. Typically we don't - we're drawn to beginnings, to arisings, to new things. Sooner or later they always come to an end, but by that time we've already moved on. Carefully skating over the moment of vanishing can help our minds to preserve the illusion of permanence and reliability that I mentioned earlier - and so paying particular attention to that moment of vanishing can help to puncture that illusion more deeply than simply observing impermanence in a broader way. In fact, paying attention to cessation is such a powerful practice that renowned meditation teacher Shinzen Young - who is famous for his vast collection of practices and elaborate systems organising them all together - has said that if he could only teach one practice for the rest of his days, it would be 'just note "gone"'. (You can read more of Shinzen's thoughts on the subject here.) Paying attention just to the vanishing of experience might perhaps sound nihilistic at first sight, but like a lot of seemingly negative practices from early Buddhism, it's actually intended to bring about a more balanced view. There's a practice in the Satipatthana Sutta which is all about contemplating the undesirable aspects of our bodies - translators often use frankly alarming terms like 'contemplating the foulness of the body' to describe it. My teacher Leigh Brasington skips right over that practice when he teaches the Satipatthana Sutta, pointing out (quite rightly) that we already have way too much negative feeling towards bodies in our culture as it is. But the Buddha wasn't trying to body-shame people - he was operating on the assumption that it's quite common for people to 'exploit their bodies for pleasure', as Ajahn Sumedho puts it. We feel down, so eat a bit of chocolate to get a quick lift in mood. We see someone who has a pleasing body, and perhaps that gives rise to lustful thoughts. And so on. So the idea of the body contemplation is to point out that, while there are attractive qualities there, they're also balanced by unattractive qualities that we tend to overlook or brush under the carpet. In just the same way, in the present discourse we aren't choosing to focus on the ending on experiences because we're trying to cultivate a negative view of the world. Rather, we're trying to arrive at a place of balance, where we can see both the attractive and the unattractive qualities of whatever arises. We can appreciate what's here while it's here, but we also know it won't last, and we shouldn't rage too hard against the unfairness of the universe when it does finally pass away. Continuing the 'river' analogy from above, it's as if we've now turned around on our little bridge to face upstream, and we're looking straight down, noticing the very moment when each twig or stone disappears from view as it passes underneath us. In the previous step, we saw things floating away, but slowly and gradually, in a way that could potentially still support a sense of a kind of permanence. Now we're seeing things vanishing, moment by moment, in a way that's impossible to ignore. When we have a clear sense of cessation, we move on to the final step of the discourse... Step 16: Letting go Where has all this practice brought us? We started by tuning in to the impermanence of the world - the shifting, changing, ultimately unreliable and unsatisfactory nature of all things. Then we turned toward the 'second half' of experience - the fading away, the inexorable current of life which will sooner or later take all that is ours, dear and delightful as it might be, away from us. Next, we focused specifically on that moment of disappearance, counteracting our tendency to focus on the new and avoid confronting the inescapable reality of cessation. If we see these things truly, deeply and repeatedly, we arrive at the final stage of the practice - letting go. We realise, beyond any doubt, that it's simply impossible to hold on to anything in this life - possessions, relationships, even our own bodies. In the Zen tradition, teachers often refer to our conventional lives as 'this floating world', which is an image I particularly like. I imagine a kind of village made up of rafts, bobbing up and down on the water currents, lashed together with ropes but forever moving from side to side, always just one bad storm away from coming untethered entirely. We go to great lengths to avoid seeing the world in this way. We make buildings out of stone, brick and concrete, imposing straight lines and right angles on nature's curvature. We use air conditioning to keep our environments at a fixed temperature, immune to the changing seasons beyond the double-glazed windows. And yet, ultimately, all of this is an illusion too. We can't control anything, really. We can't prevent things from changing, nor should we try to - to do so is to deny the innate vitality of the universe, to crush the life out of what we love so that we can somehow preserve it, but in so doing killing the very thing we wanted to save. Rather than approaching life with a clenched fist, trying to hold on tightly and keep things just the way we want them, Buddhism invites us to open our hands instead. 'Letting go' doesn't mean 'getting rid of' - we don't have to give away all our possessions and avoid all relationships 'in case we get attached'. But it also means not imposing, not demanding, not requiring things to be a certain way. We appreciate the good things that come into our lives - perhaps appreciating them all the more for the recognition of their impermanence, rather than taking them for granted until one day they're no longer there. And we endure the bad things that assail us, using the equanimity that we've cultivated through our meditation practice to maintain a sense of perspective that even this is impermanent too. In terms of the river analogy, this is the point where we no longer stand apart from the river, observing it from a distance, but instead slip into the water and allow it to carry us along. May you be carried by life's river.. Anapanasati Sutta, part 3This week we're continuing once again with our discussion of the Anapanasati Sutta, looking at the third section (or 'tetrad') of practices. Each step in the Anapanasati Sutta builds on the ones that came before it, so there will be a few references back to the previous parts (part 1, part 2) - it may be worth reading those first before proceeding unless you're already familiar with this discourse.

Moving into the third tetrad - 'turning the light around' As I've noted above, the Anapanasati Sutta consists of sixteen sequential steps grouped into four 'tetrads' (subgroups of four steps each). In the first tetrad, we focused on the activity of the body, first by examining the breath, then broadening out our awareness to encompass the entire body. Finally, we allowed our comparatively coarse bodily activity to calm down sufficiently for it to fade into the background, allowing us to observe the subtler activity of the mind with greater ease. In the second tetrad, we then began that transition toward examining subtler phenomena, first starting with subtle/energetic body phenomena, then moving into the purely mental. Finally, and in parallel with the last section of previous tetrad, we allowed our mental activity to calm down as well, allowing us to observe something subtler still. And, apart from the activity of body and mind, what else is there? In his essay Fukanzazengi (Universally Recommended Instructions for Seated Meditation), Zen master Dogen says this: You should stop the intellectual activity of pursuing words and learn the stepping back of turning the light around and shining back (ekō henshō); body and mind will naturally drop off and the original face will appear... Think of what doesn't think. How do you think of what doesn't think? Nonthinking. This is the essential art of sitting meditation. (Emphasis mine.) Many meditation practices are focused on the 'events' in our experience - a bodily sensation, a thought, a sound, a visual image. We tend to think of these as corresponding to 'things' which are 'out there in the world', but from the subjective perspective they're better thought of as 'events'. An event is something with a beginning, middle and end. Every sound, every thought, every sensation in the body begins at a certain moment in time, has some duration (be it long or short), and finally comes to an end. Examining the 'events' of our experience can lead us to deep insights into fundamental Buddhist principles such as impermanence, and as such is well worth doing. Another approach, however, is to examine the 'mind' (or 'awareness') that experiences those events. What is it that hears the sounds around us? What is it that feels the sensations in the body? What is it that thinks the thoughts flowing through each moment of experience? Dogen describes this investigation as 'turning the light around' because you won't find the answer 'out there'. There's no 'event' which will reveal that which experiences the event - what we're trying to find is the very thing which is looking at all of those events. So instead we must try to find a way to turn our awareness back on itself. That is the work of the third tetrad of the Anapanasati Sutta. The third tetrad Here's what the Buddha has to say for this section: One trains thus: 'I shall breathe in experiencing the mind'; one trains thus: 'I shall breathe out experiencing the mind.' One trains thus: 'I shall breathe in gladdening the mind'; one trains thus: 'I shall breathe out gladdening the mind.' One trains thus: 'I shall breathe in concentrating the mind'; one trains thus: 'I shall breathe out concentrating the mind.' One trains thus: 'I shall breathe in liberating the mind'; one trains thus: 'I shall breathe out liberating the mind.' As mentioned in previous weeks, each tetrad is associated with one of the four satipatthanas, key aspects of mindfulness practice in the early Buddhist tradition which are elaborated in great detail in the Satipatthana Sutta (on which I've written a whole series of articles). Appropriately enough, the third satipatthana is concerned with the mind. In the Satipatthana Sutta, however, 'mind' is pointed to indirectly, through an examination of 'mind states'. We're invited to determine the difference between 'a mind with greed' and 'a mind without greed', 'a mind with aversion' and 'a mind without aversion' and so on. This investigation can reveal some surprising results. It certainly appears to us that our experience of the world is pretty 'objective' - I see a table, you see the same table, we agree that there's a table there. Anything else would be madness! But what we find when we look at our mind states is the extent to which they colour our experience. Maybe you've had the experience of being in a rush to get somewhere, and wouldn't you know it, every bad driver is out on the roads today, all the traffic lights are against you, every little thing is annoying. So unfair! Then again, maybe you've had the experience of being pretty chilled out, maybe on holiday or at a weekend, and although the person you're with is getting very worked up about something, you don't see why it's such a big deal. Just let it go! What we discover when we explore our mind states is that our state of mind has a powerful impact on our overall experience of the moment. There's more going on in every single moment of our lives than we could possibly take in all at once, which means that our minds have to be selective - something within us has to decide 'these bits are important and need to be highlighted, and everything else can take a back seat'. And when we're in a negative frame of mind, the negative aspects of our present-moment experience tend to be sharply highlighted, whereas when we're in a positive frame of mind, the world appears softer and gentler. The world is the same (it really isn't a conspiracy of slow drivers trying to get in our way!) but our experience of it is different - because our mind is different. So that's the Satipatthana practice - pointing to the mind indirectly, by inviting us to examine our mind states and see what effect they have on our experience. The Anapanasati practice is more direct - we're simply invited to 'experience the mind' directly. How do we do that? Step 9: Experiencing the mind The key to this step is to become aware of awareness, to know that you are knowing. Find a nearby object and look at it for a few moments. You're knowing the object. Now, see if you can notice that you are aware of the object. The object is still there, but your focus has shifted from the object itself to your knowing of the object. It's a subtle thing at first, but with practice you'll get the hang of it. A practice like Silent Illumination leads us toward this 'awareness of awareness' quite directly. We begin by focusing the mind on the body sensations, so that it's less prone to distraction. Then we open up to become aware of everything in the field of experience, so that we're not focused on any particular event. As we continue to rest in this open awareness - essentially, declining to take an interest in the events of experience no matter how exciting they might be - it's very natural for awareness to flip around and take itself as an 'object'. Another way of looking at it is that Silent Illumination practice invites us to be aware of everything - the entire contents of awareness - and as such leads us in the direction of noticing awareness itself. It can help to have an attitude of being aware of 'experience as a whole' rather than 'lots and lots of sensations all at once' - the latter is still approaching experience from a separative, 'divide and conquer' mindset, whereas the former tends to have a unifying quality to it that helps to step out of the 'event perspective' and shift into the 'mind perspective'. I found it very helpful to train myself to rest in this sense of 'experiencing all of awareness at once' when I was trying to 'experience the mind' for myself. Maybe some of that helps, or maybe it sounds like gibberish! I remember very well when I was first getting into this style of practice that I would spend many hours poring over instructions like these, trying and failing to make heads or tails of them. Just keep at it, and sooner or later it'll click. When it does, the experience is often described as like finding a 'still point' in awareness, a feeling of having found something that doesn't come and go and doesn't change like the 'events out there' do. This experience can actually be a bit misleading, and can lead to people reifying 'The Mind' as the 'One True Thing That Really Exists', or the 'Eternal Witness' or what have you. Actually, when we explore the mind more deeply, it can't be found - it's just as empty as everything else. But we can cross that bridge when we come to it. For now, if you're trying to 'experience the mind' and you discover a 'still point' in awareness, it's likely that you're moving in the right direction. For me, that 'still point' felt like it was slightly 'behind me' somehow - I resonated very much with a description given by a highly experienced practitioner, who said 'It's like standing with your back to a still lake. You can't see it, but you know it's there.' See if you can find the still lake, then learn to rest there. Steps 10 and 11: Gladdening and concentrating the mind As Bhikkhu Analayo points out in his book on this discourse, once you find a way to 'experience the mind', the next two steps tend to happen pretty automatically provided you stay with the practice. The 'gladdening' described in step 10 is a much subtler experience than the kinds of 'joy' and 'happiness' we discussed in last week's article. Those are comparatively coarse emotions which arise out of the experience of having calmed the body and mind to some extent, but are still tied up in the causes and conditions of the relative world. By comparison, when we're able to rest in awareness of awareness, that experience turns out to have a subtle inherently pleasant quality to it. It doesn't matter what's going on externally - if we're able to maintain awareness of awareness, that inherently pleasant quality can be found. To find this for yourself, I suggest first getting step 9 nice and clear, and then simply noticing 'Hey, this is nice.' Don't go looking for big eye-popping bliss, just notice that there's something quietly, subtly pleasant about resting in awareness of awareness. (In the Zen tradition, it's sometimes called 'a place of thin gruel and weak tea', to emphasise the subtlety of the experience compared to the kinds of coarse sensory pleasures we're typically accustomed to. The experience of the mind actually becomes profoundly beautiful in time, but at first it's usually pretty subtle. You're probably better off looking for a sense of 'Hey, this isn't so bad' rather than 'Holy cow, this is amazing!') As you continue to stay there, the mind will 'concentrate' further - which means that the mind become less and less prone to distraction, less and less likely to be pulled back 'out' into the world of events. (We aren't talking about the kind of 'concentration' in which attention is narrowly focused on the square millimetre of skin below the nostrils - again, the mind is not a thing, not an event that we can focus on in that way.) As with steps 4 and 8 in the previous tetrads, there's nothing particular that needs to be done to make this happen - it's actually a 'refraining from doing anything else'. So just keep coming back to the mind, and noticing that subtly pleasant quality, over and over, and the mind's tendency to wander will diminish further and further over time. Step 12: Liberating the mind 'Liberation' is a term that shows up in a few different contexts in the Pali canon. Perhaps the best known is the idea of total liberation from suffering, achieved through full awakening. That probably isn't what's meant here, though - while I wouldn't want to stop you getting fully awakened at step 12, we do have four more steps to go, so it's likely that the Buddha had another kind of liberation in mind. A more likely possibility is that the Buddha is talking about liberation from the five hindrances - sense desire, aversion, sloth and torpor, restlessness and worry, and sceptical doubt. These are potentially significant obstacles which can derail our practice, leading us off track or even pushing us into giving up completely. We study the hindrances in the context of jhana practice - in order to enter the jhanas it's necessary to abandon the hindrances at least temporarily, for which my teacher Leigh Brasington and I recommend developing 'access concentration' - that is, a sufficient level of concentration (non-distractibility) to suppress the hindrances temporarily and enter the jhanas. Since the present step comes immediately after 'concentrating the mind', one fairly natural interpretation of this step is therefore that it's about liberating the mind temporarily from the hindrances. That would make step 12 a natural extension of step 11, and thus all four steps in this tetrad follow naturally from resting in the experience of the mind, simply allowing our concentration to deepen more and more. Alternatively, we might look at step 12 as an invitation to 'liberate the mind' in another way - either through the jhanas or the Brahmaviharas. For example, Majjhima Nikaya 70 refers to the higher jhanas (5-8) as 'peaceful liberations', while MN111 describes Sariputta progressing through all eight jhanas with a mind 'liberated, detached, free from limits'. Meanwhile, in MN127 the Brahmaviharas are described as the 'limitless release of the heart' - another form of liberation. If we go the jhana route, then steps 1-11 become a process for developing access concentration, then at step 12 we enter the jhanas, before moving on to our insight practice in steps 13-16 (which we'll cover next week). That would align this discourse quite well with the 'concentration first, then insight' approach which is taught elsewhere in the Pali canon. The drawback is that, unless you already know the jhanas - which are pretty difficult to learn outside of a retreat environment - then you won't be able to progress beyond this point. If we go the Brahmavihara route, we have to be a little careful. The first 11 steps of this discourse have been leading us from comparatively coarse experiences of bodily and mental activity to the subtler experiences of the 'mind in itself'. We don't want to shake things up too much by moving to a practice which takes place at a coarser level of experience - but the Brahmaviharas are often practised by bringing to mind a sequence of people, perhaps visualising in a certain way or using phrases to evoke emotions, and so forth. All of that belongs to the realm of physical and mental activity which we left behind in the previous tetrads. What we can do, however, is focus a little more on that sense of 'gladdening the mind' from step 10. Let's say that we found our way to an 'experience of the mind' in step 9 by opening up our awareness to take in 'everything everywhere all at once'. (Sorry, couldn't resist. Michelle Yeoh is a legend.) That 'holistic' approach to awareness can lead us very naturally to 'turning the light around' and becoming aware of awareness itself. Then, in step 10, we notice that awareness of awareness is inherently pleasant. If we can stabilise both of these, then all we have to do is to notice that 'awareness' and 'the contents of awareness' are two sides of the same coin - actually inseparable, indivisible. There's no 'awareness' separate from its contents, nor 'contents' separate from the awareness of them. This is a subtle point, but if we can see it then that 'inherently pleasant' quality associated with awareness can become an 'inherently pleasant' feeling toward all of experience - a truly universal loving kindness. At this point, we don't need to send loving kindness to one person at a time, or even 'radiate' it in all directions - instead, love is infused into everything we experience. (You'll sometimes hear teachers say that the true nature of everything is love - that's what they're getting at.) So we have a few options here. Perhaps we simply continue to deepen the progression from steps 9-11 into step 12, further concentrating the mind and liberating it from the hindrances. Perhaps we shift into the jhanas and allow those to sharpen our minds still further. Or perhaps we invoke the universal loving kindness that's accessible through this 'awareness of awareness', and rest there. All three of these approaches are beautiful, intrinsically rewarding, and will also set us up very effectively for the final tetrad - which we'll come to next week. See you then! Anapanasati Sutta, part 2This week we're continuing with our discussion of the Anapanasati Sutta. We covered the background of the discourse last week, so if you haven't read that article already it's probably better to start there.

Moving into the second tetrad, and the progression of the Anapanasati Sutta In the first tetrad, we used the breathing first to establish a basic level of mindfulness, then proceeded to refine it by giving ourselves progressively subtler and more challenging tasks: to become aware of the lengths of the breaths in relation to one another; to expand our awareness to encompass the whole body, without losing the breathing in the process; and, finally, to incline towards calming bodily activity. This final step is important because bodily activity is comparatively coarse, and the second tetrad is going to ask us to look at something subtler, namely mental activity. If there's too much 'noise' from the body then we won't be able to detect the subtler aspects of experience that the second tetrad invites us to examine - or at least not so easily. Actually, it's by no means impossible to turn the attention toward the subtler aspects of experience even without first calming the bodily activity. If we know what we're looking for, it's usually possible to tune into pretty much any aspect of experience. The challenge is to stick with it, and to perceive it clearly enough for the practice to have a significant impact on us. In the world of insight meditation, it's certainly possible to turn one's attention to impermanence right away, without any prior preparation - such an approach is commonly called 'dry insight'. The difficulty with dry insight is that our minds tend to be pretty unruly, easily distracted and prone to wandering for extended periods, so the meditation that results is not very efficient - perhaps you spend a few seconds looking at impermanence, then the mind wanders for a minute or two, then you realise what's happened and go back to looking at impermanence for another few seconds before the mind wanders again, and so on. With time and practice, of course, you'll get better at it, and the mind learns to stay with the inquiry more consistently. But another school of thought suggests that it's fruitful to spend some time stabilising and focusing the mind (e.g. with a samadhi practice of some sort) before moving on to insight practice - yes, it means you have to spend some time up front not doing insight practice, so you either have to sit for longer or have less time for insight work overall, but the trade-off is that the mind is calmer, clearer and better suited to the insight work, so the time you do spend on insight practice is much more efficient. A common approach found in the early Buddhist discourses is to stabilise the mind through jhana practice (or sometimes Brahmavihara practice), then to shift gears and move into insight practice. That approach absolutely works and is very effective - it's what my teacher Leigh Brasington and I teach on jhana retreats, where we recommend structuring one's practice time to start with Brahmaviharas and jhanas, then shift into an insight practice taken from the Satipatthana Sutta or another source. The Anapanasati Sutta does things a little differently, though. Here we have sixteen steps of one integrated practice that combines both samadhi and insight. As you'll see over the next few weeks, some steps are more explicitly aimed at the samadhi side (e.g. step 11, concentrating the mind) while others have a strong insight focus (e.g. steps 13-15, which are explicitly pointing to insight ways of looking), but the practice itself is also structured in a very clever way, starting with the coarser aspects of experience (which are both easier to focus on and easier to investigate at first) and then gradually leading the mind through progressively subtler experiences until the mind is in an ideal place to look for the deepest insights available to us. So it's totally fine to pick out just a few steps of the Anapanasati practice and work with those - and that's what we'll be doing in my Wednesday night class over the next few weeks, because we won't have enough practice time to do all the prior steps as well as the tetrad we're focusing on that week. But it's also very helpful to bear in mind that the practice is structured in such a way that each step makes the subsequent step easier to access - so if you're having a hard time with a particular step, it might be worth revisiting the previous steps and spending more time there before moving on. The second tetrad Here's what the Buddha has to say: One trains thus: 'I shall breathe in experiencing joy/rapture [piti]'; one trains thus: 'I shall breathe out experiencing joy/rapture [piti].' One trains thus: 'I shall breathe in experiencing happiness/pleasure [sukha]; one trains thus: 'I shall breathe out experiencing happiness/pleasure [sukha].' One trains thus: 'I shall breathe in experiencing mental activity [citta sankhara]'; one trains thus: 'I shall breathe out experiencing mental activity [citta sankhara].' One trains thus: 'I shall breathe in tranquillising mental activity [citta sankhara]'; one trains thus: 'I shall breathe out tranquillising mental activity [citta sankhara].' As I mentioned last week, each tetrad is associated with one of the four satipatthanas - and the second tetrad is associated with the second satipatthana, on vedana. There's a discussion of vedana in my series on the Satipatthana Sutta, so check that out if you aren't familiar with the term and would like to know more. In brief, though, vedana is that quality of experience which indicates whether something is pleasant, unpleasant or neutral. It's often translated as 'feeling' or 'feeling tone', because vedana is about 'how something feels', but we have to be a bit careful, because we're not talking about emotions here. Vedana is 'feeling' in the sense of 'this feels nice' as opposed to 'I feel angry about xyz'. The practice given for exploring vedana in the Satipatthana Sutta is pretty straightforward - simply bring mindfulness to the vedana of your experience! In practice, when Leigh and I are teaching it, we'll often start by pointing people toward the vedana of a specific type of experience - noticing the vedana of sounds - and then invite people to broaden their practice to include the vedana of other types of sensations as well. The Anapanasati Sutta takes a different approach. It begins by pointing specifically to pleasant aspects of experience of increasing levels of subtlety, piti and sukha (more on those terms later!). Then, rather than staying with vedana but broadening out to include neutral and negative vedana, it actually goes even further and broadens out to mental activity as a whole - making a similar move to the one we saw last week in the first tetrad, where after having spent time tuning in to subtle aspects of the breath, we then opened up the awareness to encompass the whole body. The final step of the second tetrad also parallels the final step of the first tetrad - last week, the final step was 'calming bodily activity', while this week we have 'tranquilising mental activity'. So, once again, the practice invites us into the experience of one of the satipatthanas through a specific window, then broadens out our view before allowing things to settle down even further, making an even more subtle layer of experience available as we prepare to move into the third tetrad. Focusing on the pleasant - piti and sukha The first two steps of the second tetrad open up a bit of a minefield of terminology. The first step invites us to breathe in and out experiencing piti, and the second invites us to breathe in and out experiencing sukha. Bhikkhu Bodhi translates these as 'rapture' and 'pleasure' respectively, while Bhikkhu Analayo gives them as 'joy' and 'happiness' respectively. Personally, I first learnt these terms in the context of my teacher Leigh's presentation of the jhanas, where piti is a physical sensation of energy in the body (which can show up as tingling, heat or a kind of electrical or sexual sensation) and sukha is an emotional bliss, joy or happiness, both of which show up in the first few jhanas. So who's right? Well, I'm certainly not qualified to disagree with renowned scholars like Bhikkhu Bodhi or Bhikkhu Analayo, but I've practised enough with Leigh to have a very palpable sense of his interpretation of the terms. Perhaps we can split the difference and avoid having to pick a side, however. At the end of the first tetrad, we practised calming bodily activity - allowing the physical body to relax so that we could experience subtler sensations. Anyone who has spent time doing energy practices (qigong, kundalini yoga, ...) or practices which result in 'energetic sensations' (jhanas, chanting, ...) will know that the sensations we experience in those practices are subtler than the coarse body sensations of muscular tension and so forth. In fact, too much muscular tension typically prevents us from having those energetic experiences (which is why practices like qigong and yoga place emphasis on relaxing and opening up the body). So as we 'calm bodily activity' at the end of the first tetrad, a range of subtler experiences become available to us - some of which are very pleasant. We can experience pleasure in the subtle body (which, if focused upon deeply, can lead to rapturous states of consciousness), and we can experience positive emotional states of various sorts (joy, happiness, delight), arising simply out of the calm, focused, subtle nature of the mind at this point in the practice. Generally speaking, the emotional states are subtler than the physical ones, so as the mind settles deeper and deeper, the progression is typically one that moves from the physical to the subtle body to the purely mental. Thus, one way to put this into practice might be as follows:

Focusing specifically on pleasant aspects of experience is a pretty smart move. By definition, it's a nice experience, which makes it intrinsically rewarding - and so it's generally easier for the mind to rest here and continue to become calmer and more focused than if we were paying close attention to unpleasant, difficult or distressing aspects of our experience, which are more likely to trigger a 'flinch' reaction. So although we're only focused on a small subset of the total sphere of vedana available to us (remember the 'guided tour' analogy from last week's article!), the result will get our minds into a good place to go deeper still. Mental activity - citta sankhara Steps 7 and 8 invite us first to become aware of 'citta sankhara' and then to 'tranquilise it'. But what the heck is a citta sankhara? Again, the terminology here is a bit fiddly and has multiple popular translations. 'Citta' is usually translated as 'mind', but also has connotations of 'heart' - sometimes you'll encounter the term 'heart/mind', which is an attempt to convey the fact that, whereas Western cultures posit a strong distinction between 'mind' (the rational thinky bit) and 'heart' (the emotional/intuitive feely bit), Asian cultures don't. 'Sankhara' means something like 'making together', and can be translated variously as 'formation(s)', 'fabrication(s)', 'concoction(s)' and so forth. In this instance, it's indicating the various things 'made by the mind' - thoughts, emotions, and so on - so I tend to follow Leigh in translating it as 'mental activity'. In modern times we have a very different understanding of the mind compared to the time of the Buddha. There's evidence that the Buddhist understanding of psychology evolved over time - what's found in the earliest discourses tends to be quite simple, then it becomes a bit more elaborate in the later discourses, and more elaborate still in the Abhidhamma (the 'higher teachings', texts composed after the Buddha's death) and subsequent commentaries. The later Buddhist traditions in the Mahayana also developed detailed models of 'mind', which don't always line up with what's in the early teachings. In the Western world two and a half thousand years later, the legacy of Freud and Jung has powerfully impacted how we understand the nature of mind, thoughts, subconscious and so on, so we have yet another picture of what's going on. Rather than try to pick apart every possible interpretation of the terminology, though, it's perhaps more helpful for the purposes of practice to take a step back and see what the overall strategy is here. We've used the first two steps of this tetrad to get a 'foot in the door' of the world of mental activity, by focusing on aspects of experience that particularly strike us as pleasant. (In the Buddhist understanding, vedana is regarded as a mental phenomenon, whether the vedana is associated with a physical or a mental stimulus.) Now, just as we broadened out the scope of our awareness to take in the whole body at the equivalent point in the first tetrad, we open up our awareness to become aware of the full breadth of our mental activity. Step 7 is a tricky step! Meditation practices often focus on the body because it's so much easier to work with than the mind. One thought leads to another with very great rapidity, to borrow a phrase from S.N. Goenka - before you know it, you've been sucked into a train of thought, and the meditation is forgotten. But if we've spent some time on the preceding steps and built up some stability of mind, it becomes possible to be more broadly aware of thoughts and emotions coming and going without getting drawn into them - and so we can 'safely' open up our awareness to include mental activity as a whole. Once we've successfully made the move into step 7, and we have a general awareness of our mental activity coming and going while remaining anchored on our ever-present mindfulness of the breath, we can then move into step 8 - tranquilising mental activity. Step 8 contains the same subtle trap as step 4 - the problem of how to 'actively relax'. Any positive action we take in relation to our mental activity is going to introduce more energy into the system, but in order to tranquilise it, we need less energy overall. It's like we have a jar containing some water and some sand, and the jar has been thoroughly shaken up so that the sand is swirling all around and the water is totally opaque. How do we get the water to be clear (assuming we can't take the lid off and filter it!). Shaking up the jar even more won't work, and even well-meaning things like subtly, gently tilting the jar from side to side won't help. The best thing we can actually do is to put the jar down on a table and leave it totally alone. Then, little by little, the sand will sink to the bottom of the jar, and eventually the water will become clear quite naturally. This isn't something we can make happen, and it definitely isn't a process that we can 'speed up' by applying more effort - quite the opposite. All we can do is to leave it alone and wait patiently. When that happens, we'll be ready to move into step 9 and the third tetrad - which we'll explore next week! Anapanasati Sutta, part 1

For the next few weeks we're going to be taking a look at the Anapanasati Sutta, number 118 in the Middle-Length Discourses. The name literally means something like 'The discourse on mindfulness of in-breath and out-breath', but despite the modest title it's a hugely important text for followers of the teachings of the historical Buddha - along with the Satipatthana Sutta (which we've discussed at length previously), it's one of a relatively small number of discourses in the Pali canon to give really detailed meditation instructions, and it presents a really comprehensive roadmap of early Buddhist practice.

The practice is divided into four sections (commonly called 'tetrads', because each section has four elements, so this practice has sixteen steps altogether), and so over the next four weeks we'll look at each tetrad in turn, before concluding this series (and the year!) with a broader view of the path of practice laid out in this discourse. This week we're starting with the first tetrad, which is focused on the body, but before we get into that it's worth saying a few words about a line in the excerpt from the discourse that I quoted above: 'When mindfulness of breathing is developed and cultivated, it fulfils the four foundations of mindfulness.' Satipatthana and Anapanasati - different approaches to the same terrain We've previously discussed another foundational discourse from the Pali canon, the Satipatthana Sutta. You can find the whole series of six articles on that discourse here, but for today's purposes I'll provide a brief recap. 'Satipatthana' is made up of two parts, 'sati' and 'upatthana'. 'Sati' means something like 'remembering', but in a Buddhist context is usually translated as 'mindfulness', and 'upatthana' means something like 'attending' (in the sense of 'waiting on' or 'looking after'), so the compound has a sense of paying careful attention to something, usually an aspect of our present-moment experience. Some older translators interpreted 'satipatthana' instead as composed of 'sati' and 'patthana', the latter meaning something like 'foundation' or 'establishment', and since there are four 'satipatthanas' described in the discourse, you'll often hear 'satipatthana' translated as 'four foundations of mindfulness', as in the excerpt from the sutta above. Either way, the Satipatthana Sutta lays out four aspects of our experience to which we are invited to pay careful attention. Those four are: